Deborah Samuel

fine arts photographer

Canada

The cover of the best-selling album‚ Moving Pictures‘ (5.7 million copies!) by Canadian rock trio Rush. Countless editorials (fashion especially) for renowned magazines like Esquire, GQ and Rolling Stone. Many impressive portraits of celebrities, sports heroes, musicians and writers, including Margaret Atwood (‚The Handmaid's Tale‘), singer/songwriters Alanis Morrissette and Leonard Cohen, film director Tim Burton ('Alice in Wonderland') or Queen Noor of Jordan. Since the year 2000, this photographer has returned to her basics, thus nature, in the form of taking elegant, penetrating pictures of horses, dogs, cats, birds, animal skeletons, flowers and landscapes. It is an impressive career of an extraordinary artist whose thought-provoking, creative work has come full circle but could have taken a completely different direction, too.

Deborah Samuel

fine arts photographer

Canada

If her favorite creative art course hadn’t been canned, she’d do pottery now! But things didn’t work out as desired, so this teen switched the field of study and laid the foundation for becoming famous as a photographer. ‚DS‘ moves between many different subject matters, crosses all mediums and therefore is hard to categorize. „The reason I started to work in so many areas“, she revealed in an interview with fyimusicnews.ca, „was that I always want to push my work creatively [...] to feel the freedom to do what I had to do.“

Deborah Samuel (*1956) was born in Vancouver, where her father managed an equestrian jumper barn; her mother was an equestrian jumper. The family moved to Toronto and then to Ireland when Deborah was 14 to fulfill her dad’s dream of retiring and owning and training steeplechasers. There, the teenager started photographing horses with her Kodak Instamatic camera – often from unusual perspectives or shooting things upside down.

She went to Limerick College of Art and Design for a foundation year doing sculpture, painting and drawing, but a three-day course in photography revived her old love. Nevertheless, once she had returned to her country of birth to apply at Sheridan College of Applied Arts and Technology outside of Toronto, the youngster wanted to be a potter. So, her prime focus was on ceramics. When the course of sculpture was cancelled, photography was an obvious alternative choice. „I sort of fell into it“, she’s quoted on watershedmagazine.com. „I was a good darkroom printer.“ After the two-year program and her graduation in 1977, her first job was as a printer for two fashion photographers. A year later, it was time to go solo, and she opened up a studio of her own.

Some musician friends asked the young professional to take pictures for their album cover. Then, all started taking speed on quickly as one thing led to another. Mrs. Samuel became one of Canada’s most sought-after commercial and editorial photographers/videographers in the 1980s and -90s. The artist, whose radical edgy style preferably shooting grainy, black and white portraits and fashion, lived in Toronto, New York, London, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara and finally on a ranch in Galisteo near Santa Fe/New Mexico with 26 Spanish mustangs.

After working seven days a week for 20 years in the entertainment scene, this sought-after photographer quit a business that is often out of touch with the real world. Instead of running a dual career, working commercially and doing artwork of her own, concentrating on the latter exclusively has been her focus ever since. The series of Mrs. Samuel’s projects are „fueled by her deep affinity for animals and respect for the natural world“ (rom.on.ca), added by „the cycle of life inscribed in nature“ (artsy.net).

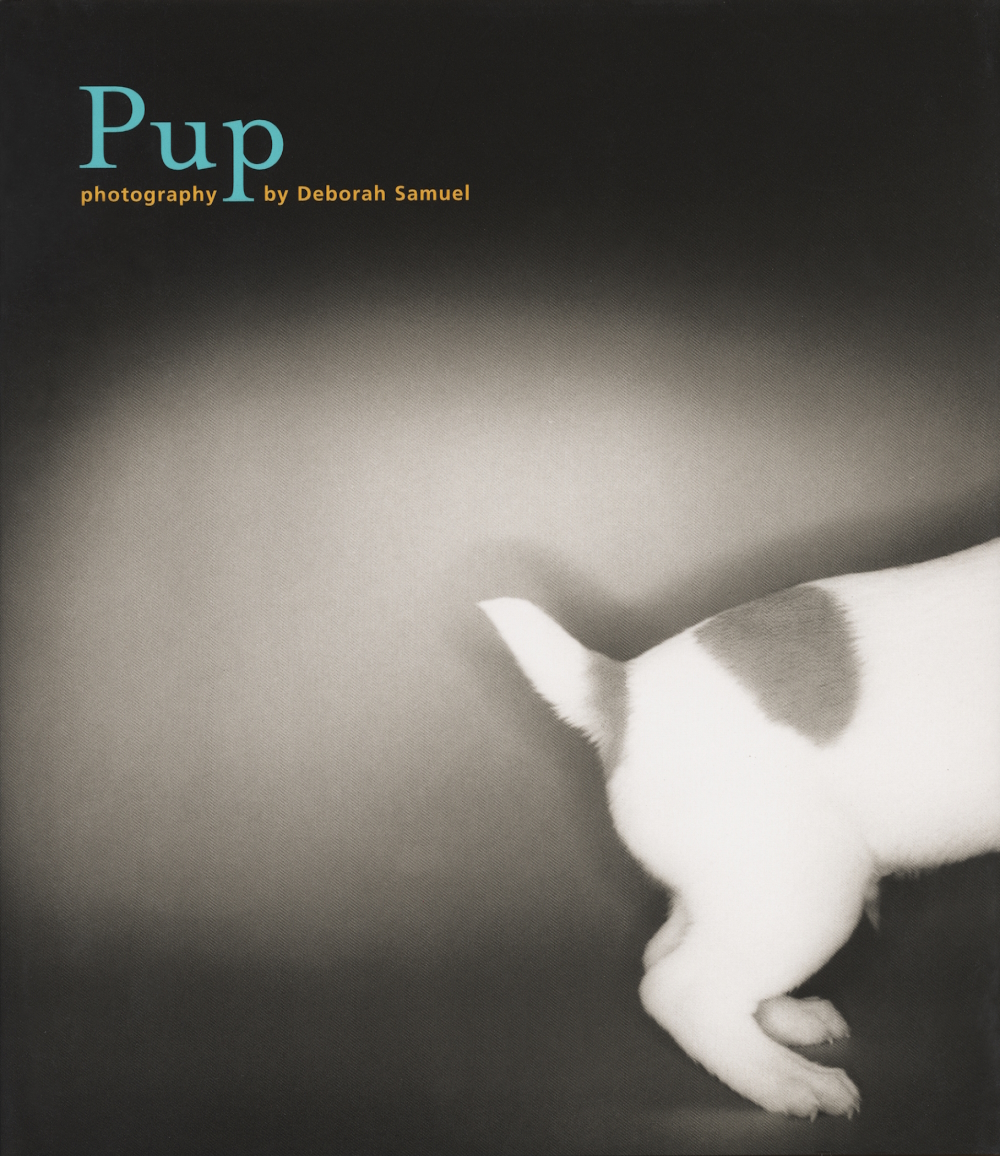

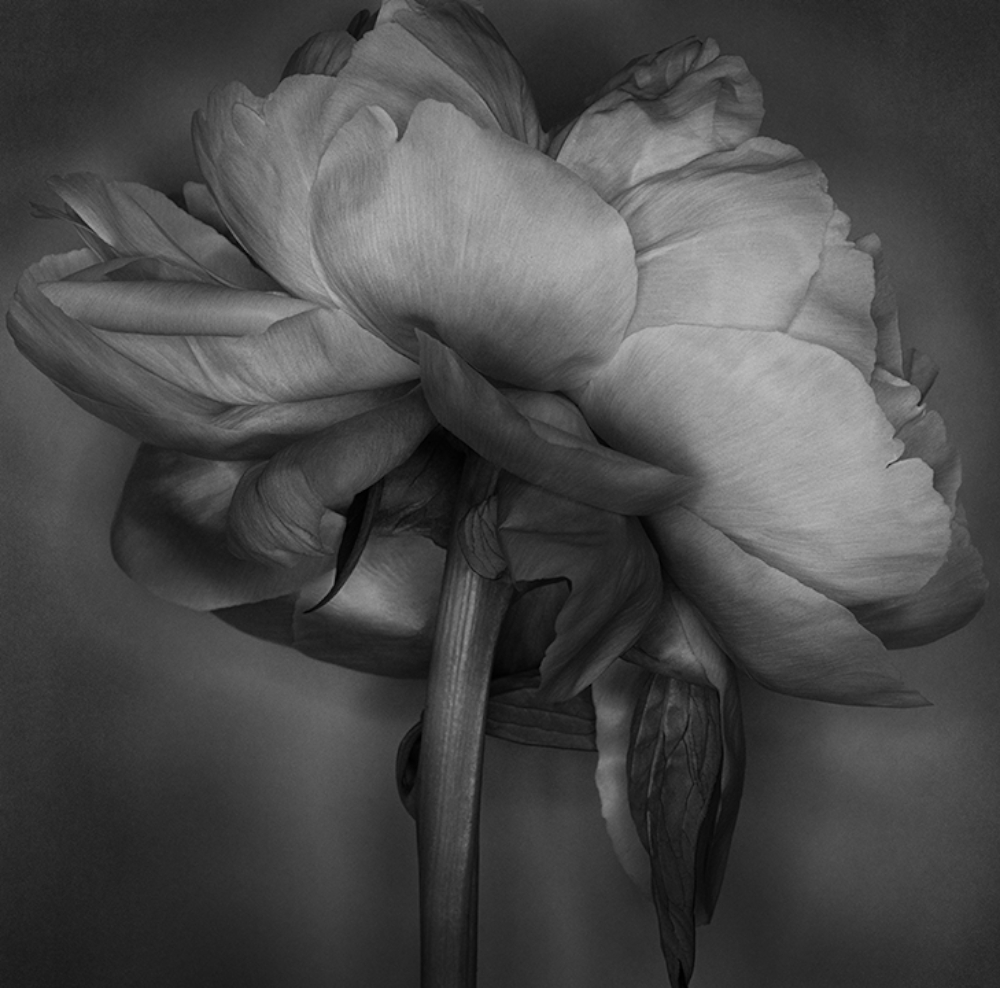

When her sixteen-year-old Yellow Labrador, Ernie, died in 1992, she noticed that she had only snapshots of Ernie. That was the beginning of photographing canines for twenty years. ‚dog‘ (2001, 112 pages) was her first book on our four-legged friends, followed by ‚Pup‘ (2002, 80 pages). Despite both being bestsellers, Deborah Samuel distanced this topic when her Boxer, Jake, died in 2005. Unsurprising that her next series ‚Passing‘ (2009), explored the journey of life and death – showing botanicals in black and white (because the vet had sent flowers to her after Jake’s death).

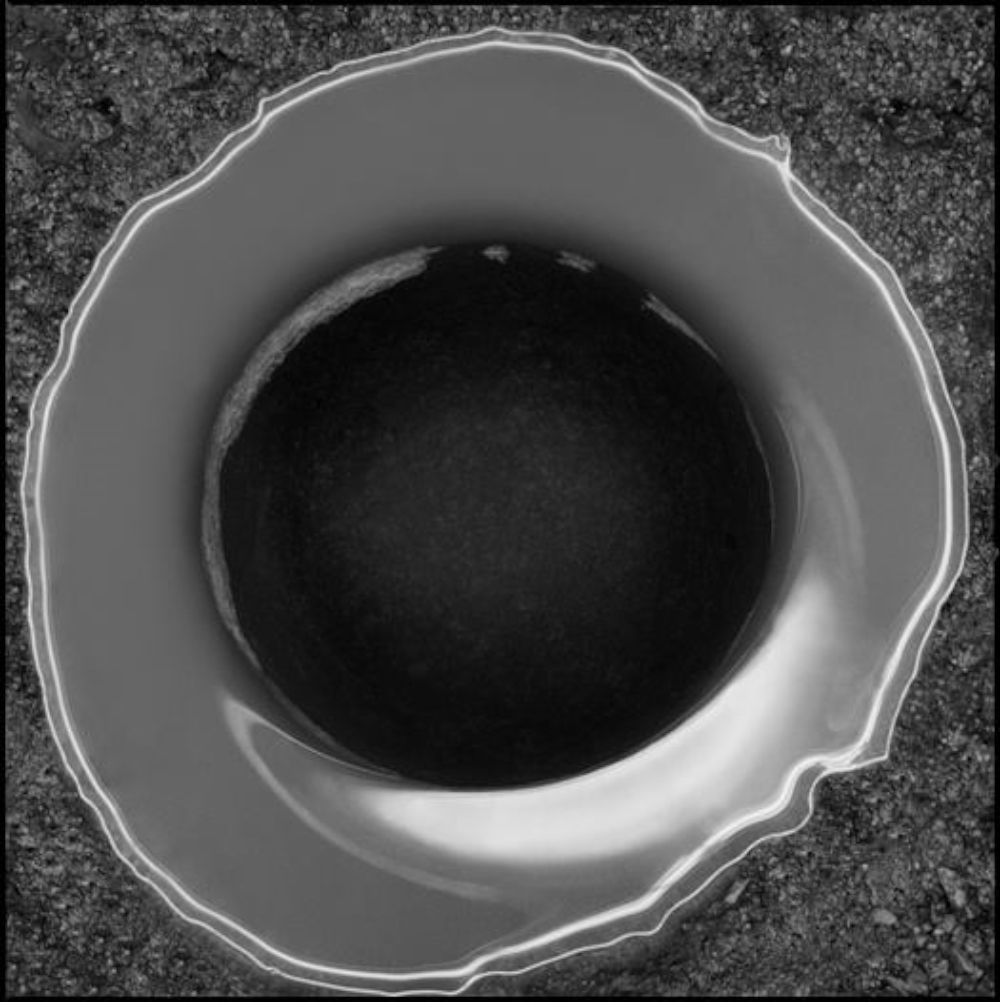

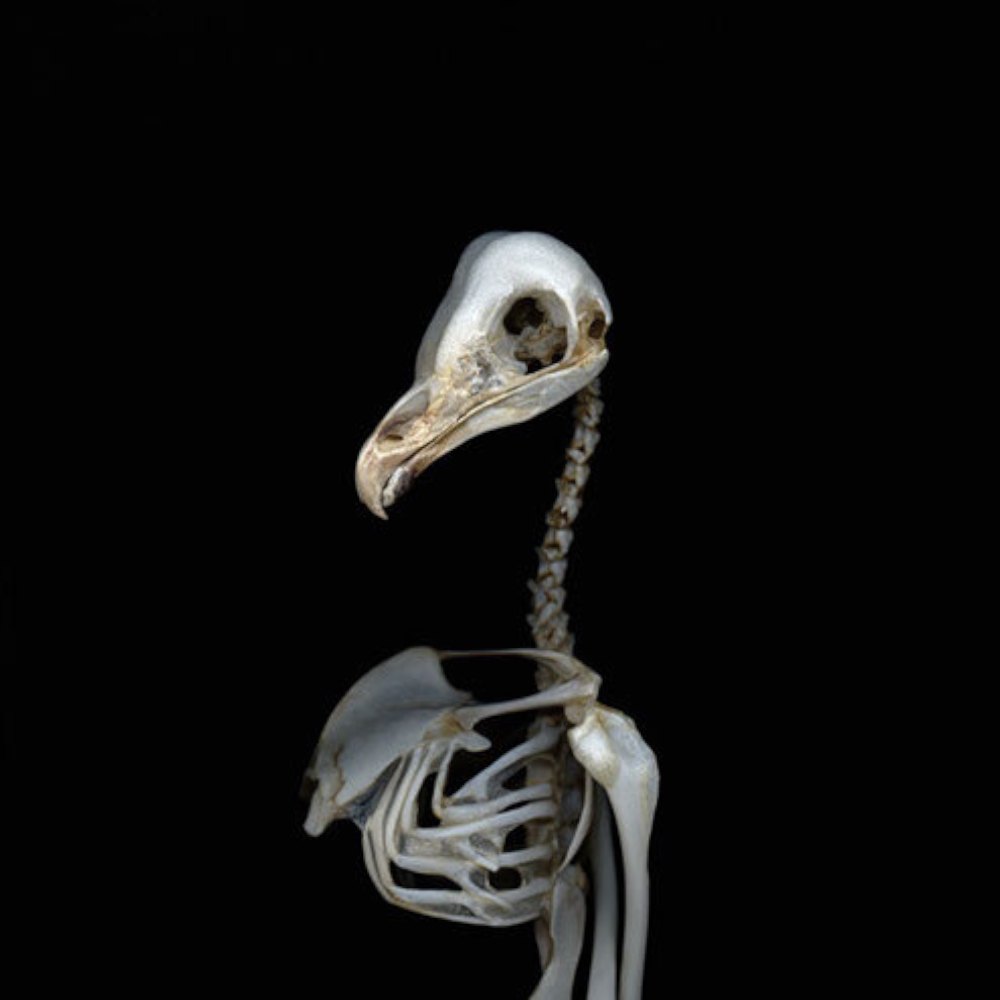

The images of bleached animal bones for 'Elegy' (2012) were photographed against black using a flatbed scanner. They were displayed at the Royal Ontario Museum Schad Gallery of Biodiversity in Toronto.

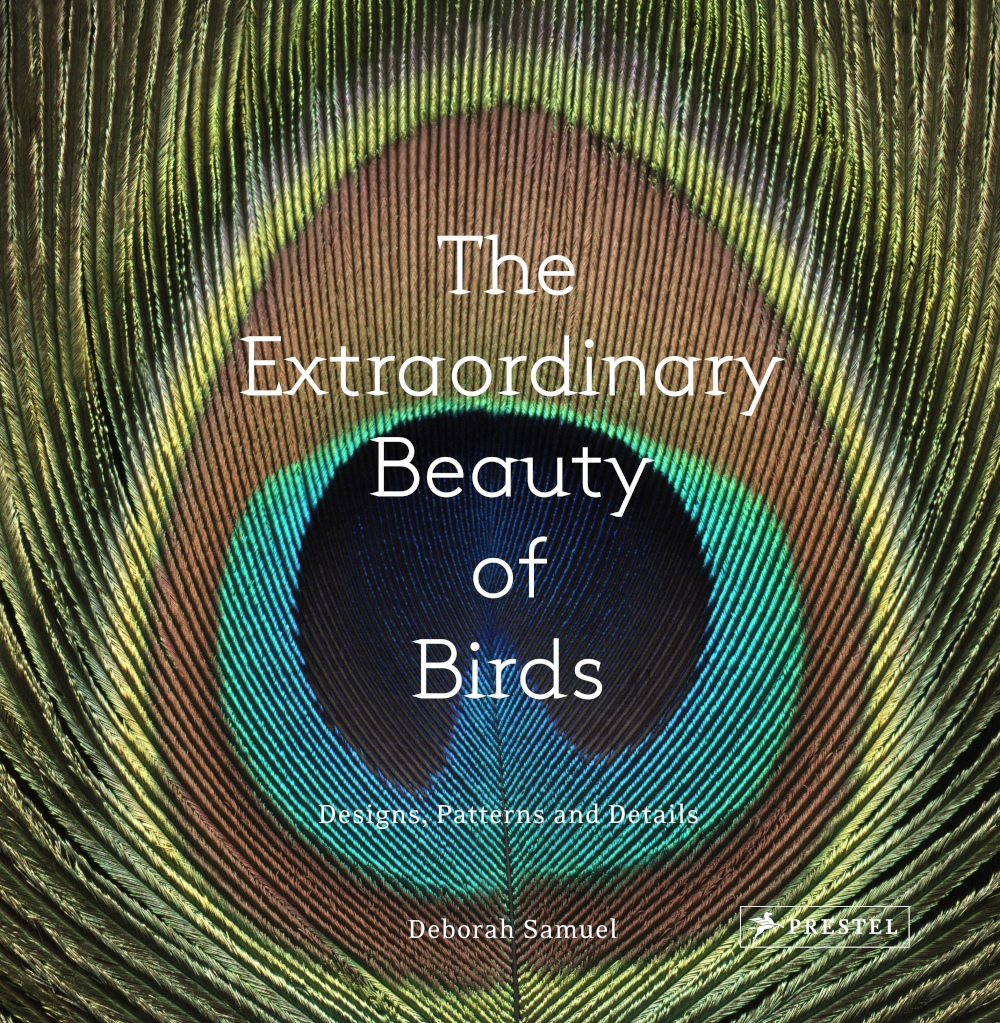

The 288 pages of ‚The Extraordinary Beauty of Birds' (2016) were realized in partnership with the ornithology department of The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). It reached second place in the book/nature section on photoawards.com: „From nest to egg to feather, these images are an exercise in seeing and a showcase of what photography can reveal: the impossibly soft feathers of ospreys; the iridescence of a bird-of-paradise; the curved, needle-like beak of a common scimitarbill; and the psychedelic hues of the aptly named resplendent quetzal.“

For ‚Artifact‘ Deborah Samuel „explored the narrative of transformation“ (gardinermuseum.on.ca). The 2017 exhibition was an homage to her beloved horse, Mao. It showed luminous photos of the animal’s ashes and stones she collected during his illness because they were like his eyes.

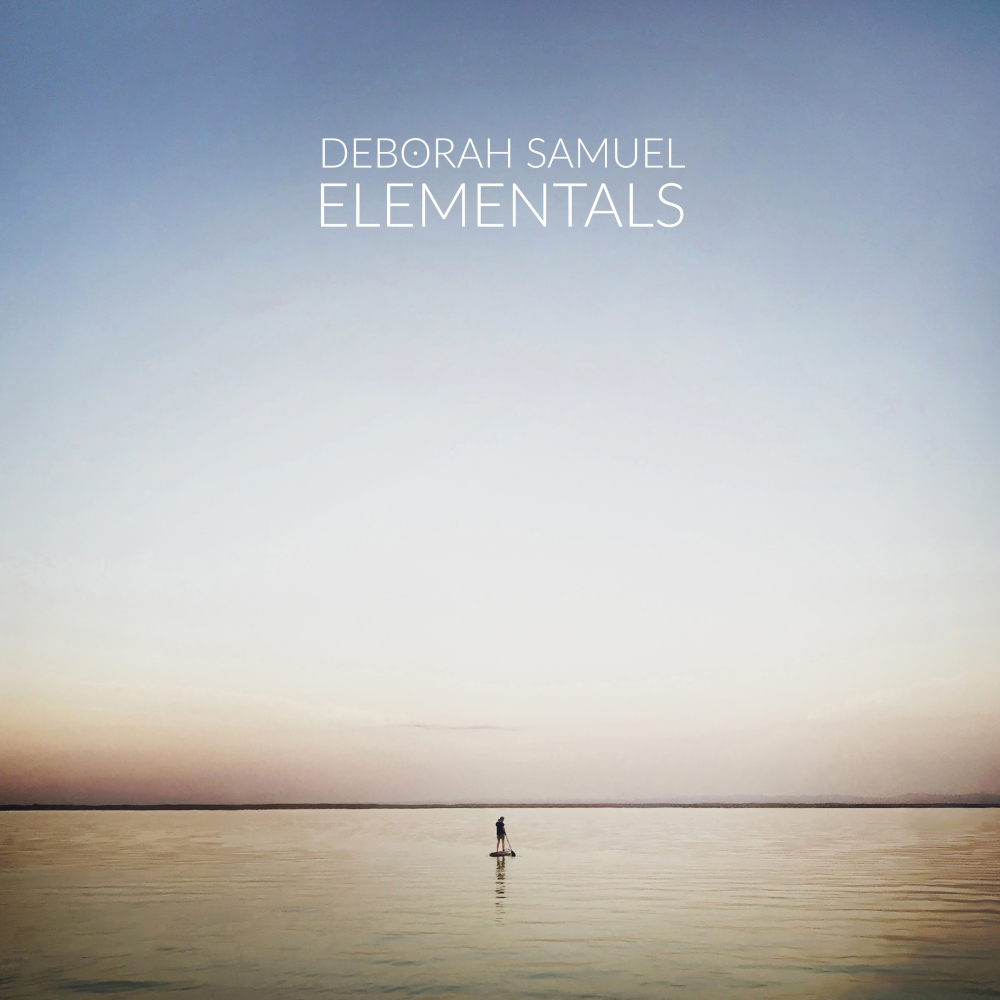

According to her, the book ‚Elementals‘ (2023, 178 pages) is „a free-form poem to the enduring beauty of the elements everywhere – earth, air, fire, and water and the transforming power of light. It is an ode to the solitude of wide-open spaces, the fluidity of shifting winds, and the monsoons’ breathtaking phenomena — environmental, atmospheric, and climatic. These elements are not just material substances. They are fundamental spiritual essences, bringing meaning and illumination to life. These photographs are my tangible memory of something too precious to ignore and too perfect to forget.”

Deborah Samuel works analog (Hasselblad square format camera) and digital (iPhone) and is inspired by deceased colleagues like Diane Arbus, Horst P. Horst, Yousuf Karsh, Arnold Newman or Irving Penn. Her central artistic style since her career redirect she described on fillermagazine.com in just six words: „I capture the essence of something!“

With decades behind the camera, this curious, experienced photographer noted some general advice on biscuitspace.com that is useful for every creative: „Follow your passion, even if you do not know what lies on the other side. Passion is infectious to people, and passion is at the root of creating art. Keep believing in your work and use your passion to help you push through and keep going. The right thing(s) happen when it is supposed to happen. Most importantly, put your work on the line and keep pushing your boundaries.“

Deborah Samuel has returned to her original home turf again and lives in Prince Edward County, Ontario, Canada, now. By the way, all her six siblings are in the arts, and two of them even reside in the same district.

Interview July 2023

Focus on evolution in reverse: from people via dogs to birds and botany

INTUITION/IMAGINATION

?: How does intuition present itself to you – in form of a suspicious impression, a spontaneous visualisation or whatever - maybe in dreams?

Generally, as a visualization. Intuition develops in many ways, from visualizations to having a feeling and listening to what the feeling is. When I work, I pay attention to what I'm feeling internally as it is how I move into whatever I'm photographing in feeling the essence of it.

?: Will any ideas be written down immediately and archived?

I don't usually write visualizations down, as many ideas and visualizations appear regularly. The meaningful visualizations keep coming back. It is how I know the important ones to pay attention to.

?: How do you come up with good or extraordinary ideas?

By exploring a subject matter that interests me in my work or, if it's a job, breaking the job down to its simplest essence. It is always about understanding the core of whatever one is working with. I let my mind go blank and watch what visual images appear. There is a fact that the conscious brain records 20,000 pieces of information per second. The conscious brain occupies 10% of the entire brain. The unconscious part of your brain, which occupies 90% of your brain, records 200,000 pieces of information per second. I wonder if one can access the unconscious part of one's brain; one has an enormous store of information that can be accessed in what has been seen or felt and recorded previously.

?: Do you feel that new creative ideas come as a whole or do you get like a little seed of inspiration that evolves into something else and has to be realized by endless trials and errors in form of constant developments until the final result?

Generally, concepts come in bits. There can be an overview or an image showing the direction. I always liken this process to being on a highway. At some point, one turns off the highway onto a minor road. One starts experimenting with the concept on a different road than the main highway you were traveling on. At times, you stay on the minor road, exploring other ways to expand the body of work you are working on. Then, you return to the main highway to move forward differently as you have developed an altered view of the overview.

?: What if there is a deadline, but no intuition? Does the first fuel the latter maybe?

There is always a solution if you open yourself to your intuition. I look at what is being shown in the visualizations. This is a practice of distilling problem-solving into visual communication to create an image that tells a story with many facets. I like working to deadlines, either given or self-imposed, as it tightens the process of working toward a solution.

INSPIRATION

?: What inspires you and how do you stimulate this special form of imaginativeness?

I worked in the commercial arena for 20 years. During this time, I took assignments that were creatively challenging, as I needed the creative element to create imagery that mattered to me. I spanned numerous arenas - entertainment, editorial portraiture, and fashion - as these were the most creative arenas to work within. Simply, it is a practice that takes time to develop and isolate what matters in creating an elastic imagination that one can bend at will.

In my personal work, I work primarily in the natural world now. Issues come up that I want to explore, and I follow what's being shown to me or what I feel passionate about. It is what imagery sticks in my mind. If it sticks in my mind, it is the start of exploring the visualization.

?: How do you filter between ideas that are worthwhile pursuing and bad ones that you just let go of?

The good ideas keep coming back, so I pay attention to visuals that keep coming back as they are the ideas worth pursuing. The visualizations that dissipate are not worth pursuing.

?: Does an idea need to appeal to you primarily or is its commercial potential an essential factor?

Any job I would do in the commercial realm would have to creatively appeal to me. It is the same with my own work. The commercial potential is not a driving force for me in my work. The driving force is a passion for a subject matter and a desire to create a feeling about a subject, that motivates the work. What matters to me is the art of communicating visual concepts of whatever I am working on.

You cannot create a large body of work without having a burning question that fuels the impetus to keep exploring the concept of the story you are creating. Creativity is fluid and powerful. It is alive in the moment, which is what photography is about. The moment.

?: Do you revisit old ideas or check what colleagues or competitors are up to at times?

I don’t go backward. Always moving forward on new ideas.

CREATIVITY

?: What time or environment best suits your creative work process — for example, a time and place of tranquility or of pressure? Which path do you take from theory or idea to creation?

Both situations - tranquility or pressure work well - they are both different ways of assessing your creativity. At times, I find driving or doing things that don’t require intellect is a great way to zone out and watch what visuals come up when my mind is elsewhere.

?: What’s better in the realization process — for example, speed and forcing creativity by grasping the magic of the moment or a slow, ripening process for implementation and elaboration?

Sometimes I wonder why I see a visualization of a particular subject. I trust my process enough to know that if I see a strong visualization in this manner, I pursue it photographically. Sometimes, it’s at the end of a body of work when it makes sense why I started where I did. I work more in the slow ripening process in creating bodies of work as each image explores many differing levels that fills out the entire work.

?: Do you have any specific strategies you use when you're feeling stuck creatively?

If I am really stuck, I will take a drive or stand in a queue… rather banal activities that create a space of nothingness. I let the ideas float in my mind without definition, just exist. This process will bubble up images if I let go of the outcome.

?: How important are self-doubt and criticism by others during such a process process i.e. is it better to be creative on your own, only trust your own instincts, or to work in a team?

Self-doubt is an essential driver in creating a career that matters. When I work on my own work, it is a solitary process of aloneness.

When I worked commercially, I found that there were designers or art directors that you could creatively align with to solve visual problems for clients. I always enjoyed the process of throwing ideas around collectively.

I always liken commercial work to visually solving a client's visual needs and my own work as visually solving my own needs.

?: Should a creative person always stay true to him- or herself, including taking risks and going against the flow, or must the person, for reasons of commercial survival, make concessions to the demands of the market, the wishes of clients and the audience’s expectations?

A creative person has to stay true to their vision and style. One develops one's style by how one views the world. Their style becomes recognized as their work and the idea of isolating the moments that matter to oneself and, in turn to others.

This comes with practice, and it comes with recognizing which jobs to take on that further your own particular vision. I chose to work in numerous arenas commercially to keep bouncing between different worlds to stay creative and inspired.

?: How are innovation and improvement possible if you’ve established a distinctive style? Is it good to be ahead of your time, even if you hazard not being understood?

One has to stay true to one's vision at all times. One has to take the risk to create images that matter to oneself and not second guess what people want. What matters is staying true to one's vision of what one feels passionate about.

?: When does the time come to end the creative process, to be content and set the final result free? Or is it always a work-in-progress, with an endless possibility of improvement?

Artists are eternally works-in-progress. There are endless possibilities to keep defining and refining how one views one's world as one moves through life. I think one’s life as an artist is defined by the work one does and is a reflection of a life lived and observed.

?: Why do you do what you do the way you do it?

I think I do what I do the way I see it and feel what Im sensing about whatever Im photographing. I trust what I feel which translates to how I see.

SUCCESS

?: “Success is the ability to go from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm.“ Do you agree with Winston Churchill’s quote?

Yes, wholeheartedly.

?: Should or can you resist the temptation to recycle a ‘formula’ you're successful with?

I believe that as an artist one has to stay ahead of technique. When I worked in the commercial realm I was known for a certain style and techniques used at a given point in time. People would want that technique that they understood my work to be. I never sat long on certain techniques - always changing them up so as to never be branded as one thing or another that people understood my work to be. I always keep moving into new subject matter and new techniques experimenting with the visual identity to tell a story.

?: Is it desirable to create an ultimate or timeless work? Doesn’t “top of the ladder” bring up the question, “What’s next?” — that is, isn’t such a personal peak “the end”?

I don’t believe you ever stop asking questions - questions beget more questions. The more one knows the more one realizes there is more to learn. There is always a continuum to further the flow of one’s life and experience from moment to moment.

MY FAVORITE WORK:

'Cobra I /II / III' is from the 'Elegy Series'. It is difficult to attempt to sum up my work in one photograph as my strength is across many different platforms in my career. The Cobra Series is a photographic series which I have always loved the power in it both metaphysically and abstractly.