Emily Young

„Britain’s greatest living stone sculptor“

UK / Italy

„Britain’s greatest living stone sculptor“! The renowned business newspaper Financial Times didn’t call her just that, but added furthermore: „she now stands quite alone in her field, not just as the pre-eminent stone-carver of her generation, but as virtually the only sculptor of her kind at all, a true carver working with figurative imagery, of any real and sustained distinction.” Permanent installations of some of her timeless works which marry the contemporary with the ancient while „highlighting natural beauty and the geological history of the earth“ (artnet.com) can be seen in St. Paul‘s Churchyard and St Pancras New Church (London), Royal Botanic Gardens (Kew), Salisbury Cathedral, the University of Notre Dame (Indiana, US) and Loyola University Chicago. Noteworthy: this praised top creative that had studied drawing and painting as a young woman became a sculptor later on – just by chance!

Emily Young

„Britain’s greatest living stone sculptor“

UK / Italy

„I had some slabs of marble left over from a kitchen work surface“, the remarkable artist told houseandgarden.co.uk, „and somebody had left a little mason's kit with a hammer and some chisels, I put the two together and loved it.“ That was a start of a great career. Its origin might be in the heritage. Her grandma Kathleen Scott, widow of the Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott, was not only a sculptor, but a befriended colleague of worldfamous Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) too! The Frenchman is generally considered the founder of modern sculpture and known for classsics like ‚The Thinker‘, ‚The Kiss‘ or ‚The Gates of Hell‘ among others.

Emily Young was born 1951 into a bohemian family of conservationists in London. Her mother was a writer and commentator, dad a politician and journalist, grandpa a writer and politician; her uncle, a ornithologist and painter, founded the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust.

Dad took little Emily for walks to visit the ancient stone circle sites of Stonehenge and Avebury. Mrs. Young spent her youth in London, attended Chelsea as well as Saint Martin’s School of Art and was a regular visitor to the Sixties‘ trendy clubs in the UK’s capital. There it is said Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd saw the teenager dancing. It inspired him allegedly to immortalise the girl in ‚See Emily Play‘, the band’s second single.

Being 17 years old, Emily Young left the bourgeois home and travelled to India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Africa and the Middle East for several years. Upon her return „she founded Public Pictures, a community-based mural group in 1974“ (artuk.org). After having lived with Simon Jeffes, leader of The Penguin Cafe Orchestra, during the 1970s & 80s, designing record sleeves and the stage appearance for the avant-pop band, she moved on. The mother of a son, who had studied under the sculptor/educator Robert White (1921-2002) in the United States, was in her thirties, when she turned fully to sculpture. Her favourite materials are alabaster, lapis lazuli, marble, onyx, but it can be limestone, sodalite, travertine also.

„I free-carve stone, pieces of the planet“, Emily Young writes on her website. „I find them in quarries, in stone yards, or in places of geological interest.

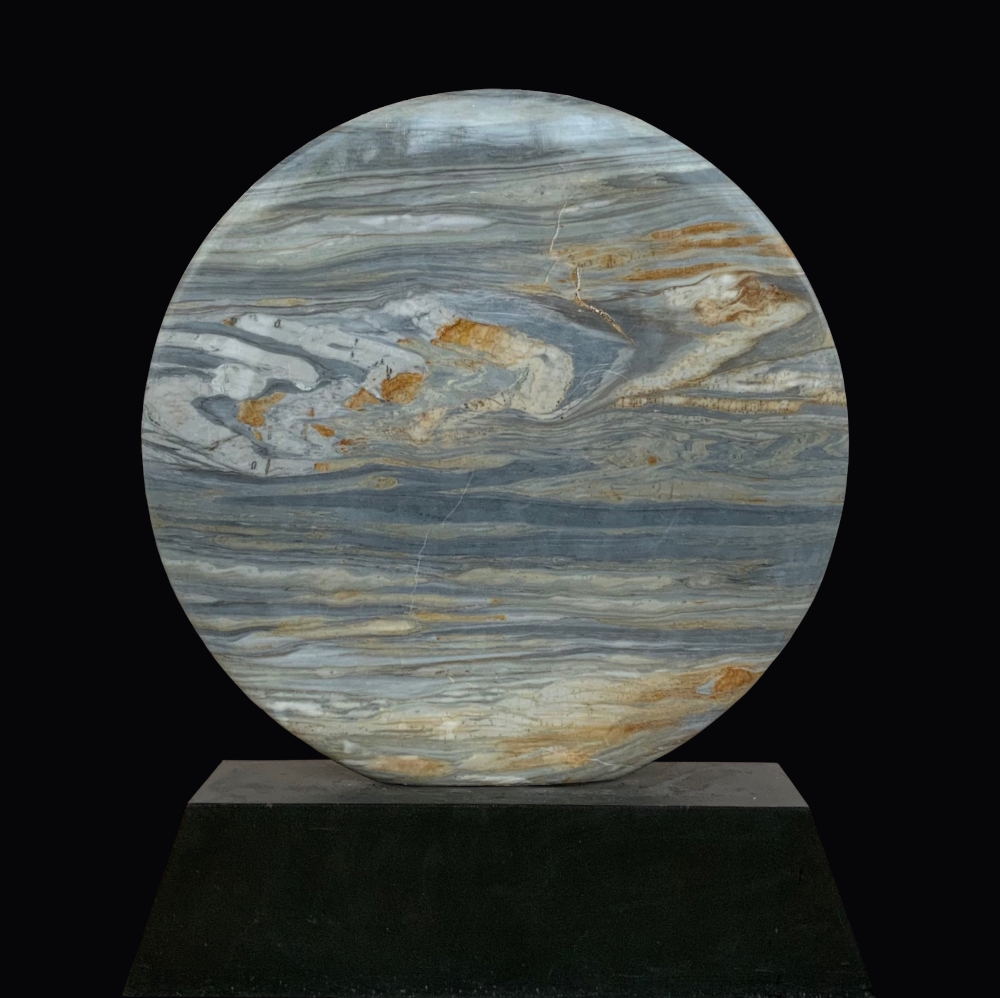

I work with pieces that speak to me in some way. They may have interesting forms in their structures, or wonderful colours, or evocative figurations on their surfaces. Guided by the stones, I carve them into heads, torsos and discs.

I put into them something of my own mind, seeing in them the history of the creation of the planet, which can then touch on the creation of our solar system, and beyond. I am also alive to the connection between all matter.“

„She uses both contemporary and ancient methods of sculpting“, states pallant.org.uk, „and her impressive pieces grapple with our relationship with the planet – marrying the human form with unruly natural shapes and textures. Each piece is wholly unique because of the geological history of her source materials, which bring their organic and spontaneous beauty to the fore. The results are serene, poetic and hugely impactful.“ „Androgynous, elegant contours and simplicity of form“ (houseandgarden.co.uk) are other key words when Emily Young’s „meditative, figural works“ (artnet.com) are described.

The completely handmade creations of this real environmental artist are held in public collections like The Getty (California/US), The Victoria & Albert (London), La Défense (Paris) or Madonna dell‘Orto (Venice) and part of private ones by various clients featuring rockstars, filmactors and major directors.

The 128 pages of her 27 cm high book ‚Time in the Stone: A Light Touch and a Long View‘ (Tacit Hill Editions, 2007) include 64 full colour photographic reproductions of her stone carvings.

Emily Young lives in Italy. Her home and studio in the southern Tuscany are in a spacious, former monastery from the 17th century called Convento di Santa Croce.

Interview February 2024

„Playing with stones“: the nature of matter is being really alive and really still

INTUITION/IMAGINATION

?: How does intuition present itself to you – in form of a suspicious impression, a spontaneous visualisation or whatever - maybe in dreams?

I live in a continuum of life and death, and my work is born through and alongside this.

?: Will any ideas be written down immediately and archived?

Sometimes written down, but more as poetry than a plan. The work is the archive.

?: How do you come up with good or extraordinary ideas?

Being a part of the universe, in human form, the brain is creative, if left to itself.

?: Do you feel that new creative ideas come as a whole or do you get like a little seed of inspiration that evolves into something else and has to be realized by endless trials and errors in form of constant developments until the final result?

I carve wild stone, and have no particular idea what the piece will turn out to be, apart from the first decision to make a head or a torso. The stone’s form lets me know about what it is, and I work with it. The discs I make are obviously going to be circular and thin….

?: What if there is a deadline, but no intuition? Does the first fuel the latter maybe?

The stone is never quiet.

INSPIRATION

?: What inspires you and how do you stimulate this special form of imaginativeness?

I was born with imagination, as are many people, and I was able to keep manifesting that throughout my life. To be in touch with the wild formations of the stony planet is an infinite journey.

?: How do you filter between ideas that are worthwhile pursuing and bad ones that you just let go of?

The stone is my teacher, allied to my skills as a carver honed over many decades of drawing and seeing.

?: Does an idea need to appeal to you primarily or is its commercial potential an essential factor?

I try to stay true to a non-commercial world view. A compassionate approach is my abiding preoccupation.

?: Do you revisit old ideas or check what colleagues or competitors are up to at times?

Over the years I have lost almost all my interest in what others contemporary to me are doing. The old ideas, from history or from my own earlier preoccupations are always with me.

CREATIVITY

?: What time or environment best suits your creative work process — for example, a time and place of tranquility or of pressure? Which path do you take from theory or idea to creation?

Stay out doors as much as I can, as far away as possible from big cities and other people, and try to pay as little attention as possible to neoliberal hyper-industrialised ways of living.

?: What’s better in the realization process — for example, speed and forcing creativity by grasping the magic of the moment or a slow, ripening process for implementation and elaboration?

Just watching my own processes in alignment with the stone, the weather and such.

?: How important are self-doubt and criticism by others during such a process?

Neither of these are useful to me.

?: Is it better to be creative on your own, to trust only your own instincts, or to work in a team?

I work alone, when working on the stone, but I also work with a very supportive small team of people who help with transport, installations, presentation, sales etc.

?: In case of a creative block or, worse, a real failure, how do you get out of such a hole?

As the British painter William Turner said: "if you can't paint, paint something else."

?: Should a creative person always stay true to him- or herself, including taking risks and going against the flow, or must the person, for reasons of commercial survival, make concessions to the demands of the market, the wishes of clients and the audience’s expectations?

Each person will make their own decisions about this, there is no one rule.

?: How are innovation and improvement possible if you’ve established a distinctive style? Is it good to be ahead of your time, even if you hazard not being understood?

There are no rules in creativity.

?: When does the time come to end the creative process, to be content and set the final result free? Or is it always a work-in-progress, with an endless possibility of improvement?

As in life, both the above come into play.

?: How does artificial intelligence change human creativity? And do you? Would will you use it at all?

Not possible to tell yet. I shall probably not go there in my life time.

SUCCESS

?: “Success is the ability to go from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm.“ Do you agree with Winston Churchill’s quote?

Not really - I’m not sure what he meant by success and failure.

?: Should or can you resist the temptation to recycle a ‘formula’ you're successful with?

Depends on the project. Time doesn’t precede freshness.

?: Is it desirable to create an ultimate or timeless work? Doesn’t “top of the ladder” bring up the question, “What’s next?” — that is, isn’t such a personal peak “the end”?

There is no end.

MY FAVORITE WORK:

Since I started working with stone, over forty years ago (wild stone as compared with quarried, six sided blocks) the pieces have increasingly become translators of human consciousness : the two entities, raw matter and human consciousness form a marriage that speaks potently of the drama of human frailty. We have disowned our Earth Mother, and the deep physical history that gave us our lives. I carved the Lost Mountain Head piece (some two tons of complex stone from the local mountain) in 2013 to protest the spreading destruction of said mountain, Monte Amiata in Southern Tuscany, by way of geothermal projects. I like to show our profound connection to the Earth, by leaving untouched the natural signs of the life of the ancient stone, and at the same moment showing the human compassion we can have, in the sight of our better natures, as opposed to our interior fools.