Iwona Buczkowska

architect / urban planner

Poland / France

"A pioneer of timber construction and a fierce defender of the right to good housing." This explanation by Mano Mollard, editor of The Architectural Review, describes prefectly the reason why this Polish-born French architect received the Jane Drew Prize 2024, an „annual award recognising an architectural designer who, through their work and commitment to design excellence, has raised the profile of women in architecture“. Furthermore the specification describes what makes that winner one of the most significant representatives in the genre. This architect of the 21st century known for an innovative approach in her use of wood as building material and advocating the use of free plan construction which facilitates movement through the building is consistent in her design style: ‚Back into the Future‘ is the obvious way to go for her! According to Wikipedia „she has been inspired by the way that towns were planned in the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the Baroque period.“

Iwona Buczkowska

architect / urban planner

Poland / France

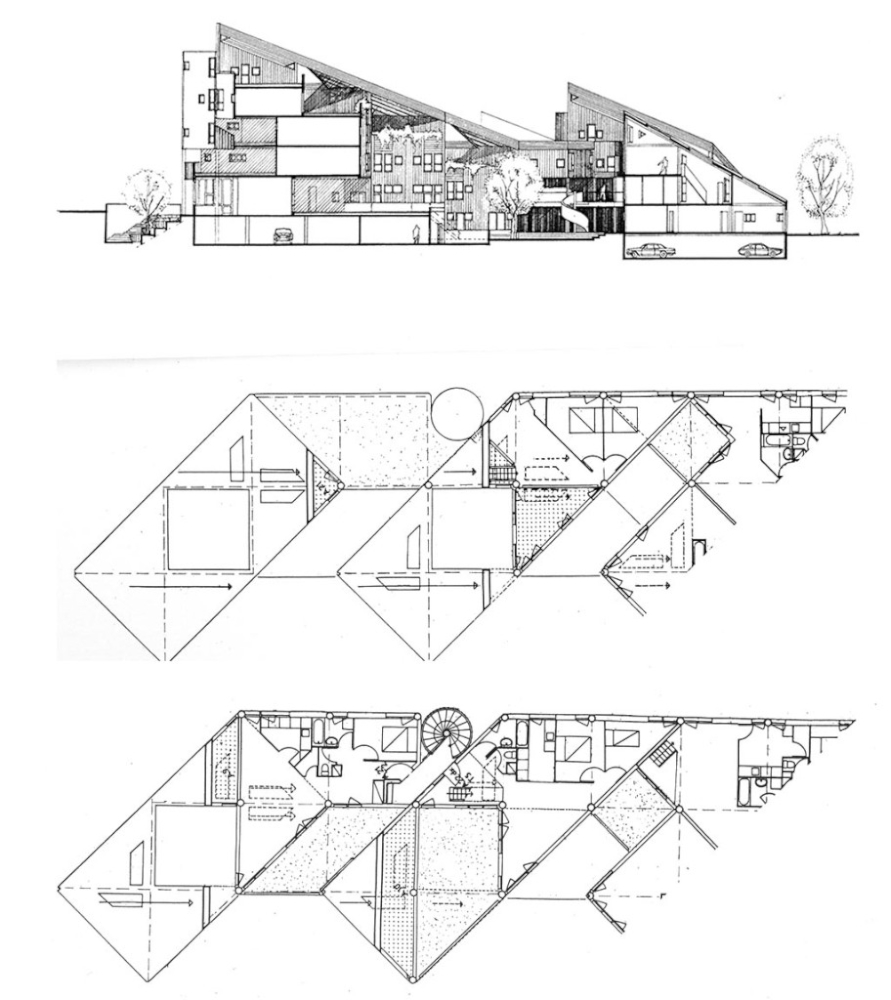

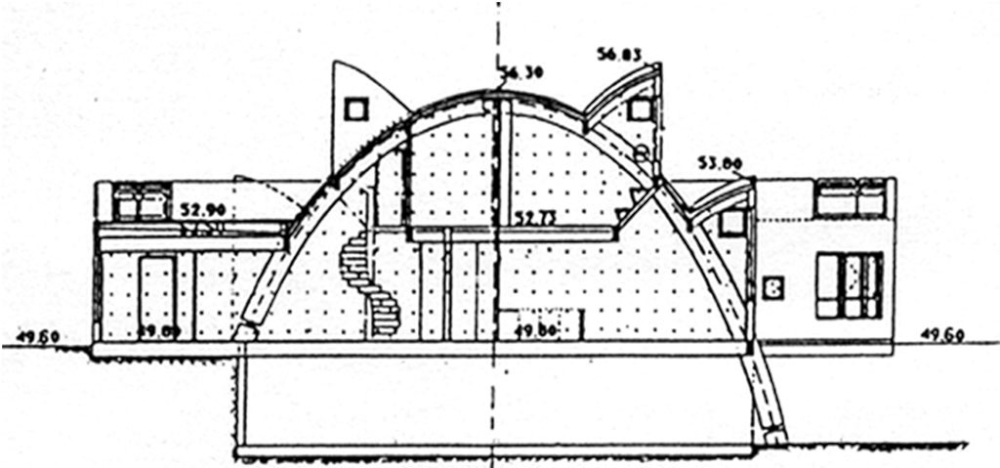

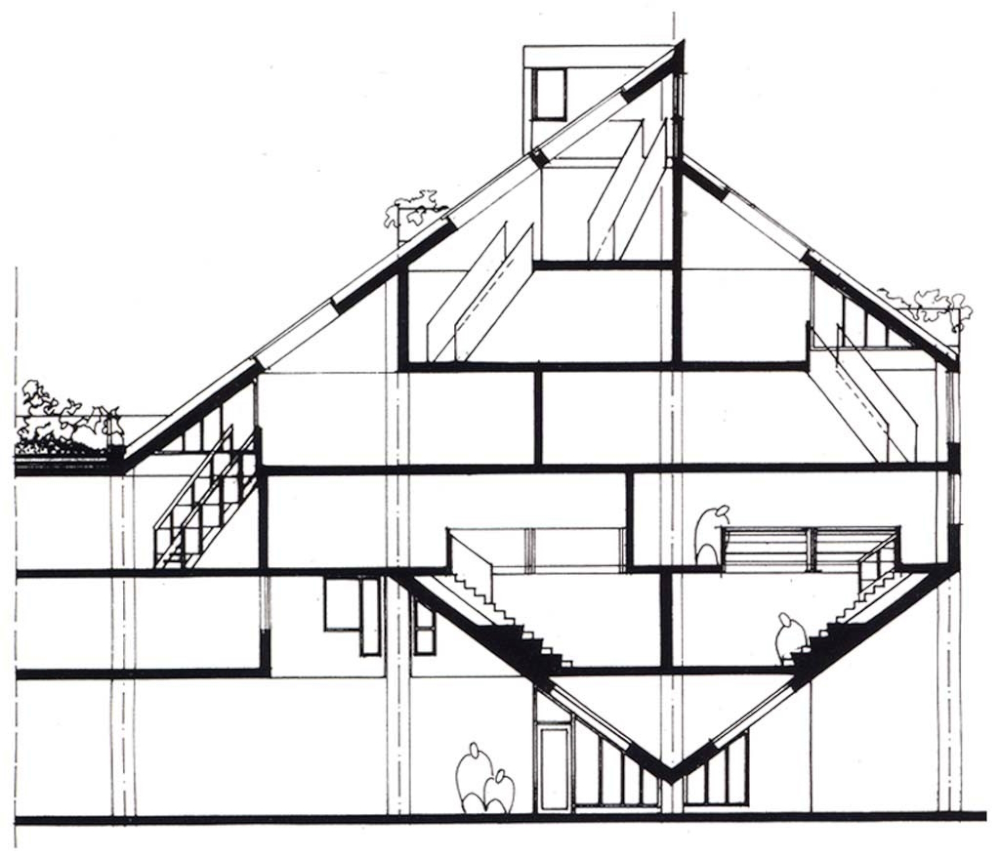

„Arches and diagonals are the specific characteristics of Iwona Buczkowska's architecture: these two geometric elements transform the architectural space into an existential space that can be experienced as a social reality.“ These sentences are to be read on Amazon accompanying her own paperback aptly titled ‚Breathing Spaces‘. „Iwona Buczkowska's projects include large school complexes as well as boardrooms and residential buildings and are characterised by their interaction with natural conditions such as light on the one hand and communal and neighbourhood life on the other. This interaction has a functional, but also a strongly aesthetic side. Buczkowska's buildings are a consistent and original contribution to contemporary European architecture.“

Becoming a praticioner of such outstanding status as an adult started with a present in the youth by the way. Here it was one that the following aphorism by the French novelist Eugène Marcel Prévost (1862 - 1941) applies to: „An acquaintance with a single good book can change a life!“ As a teenager Iwona Buczkowska (* 1953 in Sopot/Poland) received 'Art Treasures of the World' by Eleanor C. Munro. According to its subtitle the 1969 release shows „Painting, Sculpture, Architecture and Ornament, from Prehistoric Times to the Twentieth Century“. „There were several architects and a few pictures that really struck me: The Matisse Chapel in Vence, Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier’s Notre-Dame-du-Haut-Ronchamp“, she mentions in an interview with The Architectural Review accompanying her Jane Drew Prize. „These images seemed fabulous to me. I found them incredible and so I wanted to do Fine Arts." In a mail to Divine Spark's editor, Mrs. Buczkowska gets into detail regarding these times back then: "My parents believed that artists, unlike architects, have difficulty earning a living. They then suggested that I study architecture first and then Fine Art." The studies at the Gdańsk Polytechnic School were very specific. "During all the years of study, four hours per week were reserved for painting, sculpture and drawing. This training undoubtedly developed my view of architecture." The twen took the examen at the University of Technology in Gdańsk/Poland and then studied at the L'École spéciale d'architecture (ÉSA) in Paris, from which she graduated in 1974 with a degree in architecture. At the age of 23 'IB' went straight into social housing „because the time was very promising. It was the period after May 1968 in France. We all wanted to live differently and there were clients and local authorities with ambition, willing to reimagine social housing – which was dilapidated and uninteresting.“ In 1980 the Atelier Iwona Buczkowska was opened.

„As part of her studio“, notes dezeen.com, „she has completed several public buildings and social housing projects in France including Cité Pierre Sémard – the country's largest timber residential complex.“ This architect’s work was awarded numerous times. To name just a few: her honours include the Gold Medal and Special Prize at the Fifth World Biennale of Architecture in Sofia in 1989 for her project Le Blanc-Mesnil, For the same she was granted the Prix grand public de l’Architecture form the region Ile-de-France in 2003 too. Another prize was the Silver Medal and the Prix Delarue in 1994 from the Academie d’architecture for her collected work.

Her independent practice is listed on Instagram’s ‚50 studios shaping the Future of Social Housing‘. The reference is for a good reason when the much in demand lecturer and speaker at architectural schools and conferences explains her very different attitude in fighting the present situation: „Social housing is no longer seen as a field of architectural research and experimentation like it was earlier. We are building at an increasing speed with a significant decrease in quality. Discussions address technical and thermal issues as well as matters of preservation, and we ensure all the constraints imposed on architects are respected. But what about the space itself, the types of spaces we believe in, in which we want to live? The spaces that give us something more that go beyond the response to functional requirements? It seems to me that such projects with real spatial richness are non-exisent today or at least there is not the same force of expression as there was in the 1980s.“

Some aspects of what make her designs special were described during a research for a book on Parisian brutalism (in architecture): „Iwona’s work involves a very particular design method. It is an architecture of oblique geometry that rejects the dominance of the right angle to explore the design possibilities of more intricate spatial pattern“ (worldofinteriors.com).

Iwona Buczkowska works and lives in the Cité Les Longs Sillons estate, located in the Parisian south-east suburb of Ivry-sur-Seine, that she has designed too.

Interview February 2025

Back into the Future: an unconventional step that gets rewarded!

INTUITION/IMAGINATION

?: How does intuition present itself to you – in form of a suspicious impression, a spontaneous visualisation or whatever - maybe in dreams?

Intuition manifests itself in me through the impression of being drawn in an unknown direction, through a force of spatial research through models and through flashes of ideas that arise when we least expect them.

?: Will any ideas be written down immediately and archived?

Initial ideas are immediately tested by critical intelligence, others develop and are enriched over time.

?: How do you come up with good or extraordinary ideas?

Intuitive thinking refers to the ability to understand a situation and find a solution without going through an analysis process. However, every architect begins his project by analyzing the place of intervention, the program, the constraints, the budget…

It seems to me that in our greatest concentration, when all spheres of the brain are well stimulated, we then access all our cerebral abilities to capture the information necessary at a given moment. We manage to make analysis and synthesis coexist at the same time. In my opinion, it is at this moment that interesting ideas are born.

?: Do you feel that new creative ideas come as a whole or do you get like a little seed of inspiration that evolves into something else and has to be realized by endless trials and errors in form of constant developments until the final result?

Both contexts exist.

?: What if there is a deadline, but no intuition? Does the first fuel the latter maybe?

Making a project is a very complex process. Intuition can accompany the development of the project, but it is not sufficient for the production of an architectural work.

INSPIRATION

?: What inspires you and how do you stimulate this special form of imaginativeness?

Always the site, its constraints and/or its beauty, the interpretation of the program and since neither the context nor the program is ever repeated, all my projects are necessarily always different.

The painting and sculpture classes at the Polyethnic School of Gdansk, my multiple trips around the world, my bedside book 'Architecture without architects' by Paul Rudolfsky have undoubtedly formed a certain imaginary world without me being able to dissect the direct inspirations.

?: How do you filter between ideas that are worthwhile pursuing and bad ones that you just let go of?

Some ideas are self-evident straight away, they appear obvious, others deserve to be developed and verified in detail in order to accept or reject them.

?: Does an idea need to appeal to you primarily or is its commercial potential an essential factor?

I must like the idea and I must be convinced of its correctness.

?: Do you revisit old ideas or check what colleagues or competitors are up to at times?

No, never.

CREATIVITY

?: What time or environment best suits your creative work process — for example, a time and place of tranquility or of pressure?

The most favorable setting for creation is the one that allows the best concentration, especially for initial ideas, it can happen anywhere. Then the workshop setting is very conducive to the development of the project. Pressure can play a favorable role provided it is not excessive so as to cause anxiety.

Which path do you take from theory or idea to creation?

It depends on the program. In architectural projects, immediate work on the model (classic, non-digital) going through different scales and in parallel, in addition to verifying the solutions in schematic plan.

?: What’s better in the realization process — for example, speed and forcing creativity by grasping the magic of the moment or a slow, ripening process for implementation and elaboration?

Both are necessary and one follows and complements the other. Sometimes we test several solutions and finally choose the first.

?: How important are self-doubt and criticism by others during such a process?

Sometimes self-doubts can help the project progress, but they must disappear before presenting it to the Client. Criticism from others can be constructive.

?: Is it better to be creative on your own, to trust only your own instincts, or to work in a team?

I cannot answer for others. As for me, I work on each project for a long time alone to arrive at the solutions that suit me and then, in the case of important projects, teamwork develops.

?: In case of a creative block or, worse, a real failure, how do you get out of such a hole?

Take a break, stop, go somewhere to change ideas and resume the project later.

?: Should a creative person always stay true to him- or herself, including taking risks and going against the flow, or must the person, for reasons of commercial survival, make concessions to the demands of the market, the wishes of clients and the audience’s expectations?

It seems to me that true creators remain true to themselves, they identify with their works because creation constitutes their internal structure, the axis and goal of their existence.

?: How are innovation and improvement possible if you’ve established a distinctive style?

It is about designing spaces and translating them into volumes according to certain objectives which are specific to me and invariable, such as the search for light, for example, or the search for the oblique dimension. It is more about the architect's approach, and not a style, and all the better if it becomes personal. We always wait impatiently for a very good writer, or a filmmaker, for his next work, hoping that it will be better than the previous one. The same trust and hope should be given to an architect.

?: Is it good to be ahead of your time, even if you hazard not being understood?

When designing my projects I was unaware that I was ahead of my time, especially since the post-May 1968 period was very conducive to research. I was simply planning the spaces in which I would have liked to live, which today, to my great astonishment, are considered to be the realized utopias.

The gloom and regression of today's society clearly demonstrate how difficult it is to safeguard these projects. In this context, the request from tenants of Blanc-Mesnil to classify the neighborhood, their fight against the threats of its demolition, is proof of their well-being in their social housing, and gives the answer to your question.

?: When does the time come to end the creative process, to be content and set the final result free? Or is it always a work-in-progress, with an endless possibility of improvement?

There comes a time when the solutions proposed give us satisfaction. Obviously a project can always be improved, which normally happens when we move on to the next phase of the project study.

?: How does artificial intelligence change human creativity? And do you? Would will you use it at all?

Today we are witnessing numerous debates between specialists on this subject, without them reaching an agreement, so I consider myself incompetent in this area. On the other hand, I know that I will always call on my intelligence, leaving the other – the artificial one – on standby.

SUCCESS

“Success is the ability to go from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm.” Do you agree with Winston Churchill‘s quote?

The sentence is correct.

?: Should or can you resist the temptation to recycle a ‘formula’ you're successful with?

It must be very boring to “recycle” a formula and I have never been tempted to do it. In my philosophy as an architect I look for solutions that seem right to me for a given context, which itself is never repeated, which constitutes an immense wealth for the profession of architect.

?: Is it desirable to create an ultimate or timeless work?

True creation resists time. It is always interesting to continue research, thus contributing to the development of the history of our civilization. In architecture the problem is complex because it expresses the concerns of our society at the time of its designs, which can change as time passes.

?: Doesn’t “top of the ladder” bring up the question, “What’s next?” — that is, isn’t such a personal peak “the end”?

I don’t see myself “at the top”. I started working on the 225 social housing project in Blanc Mesnil when I was 23 years old. At the age of 70 I carried out a tiny project “Atelier Gold” which seems very interesting to me, remaining very different from the others following the very particular “metaphysical” program. In the current economic and political context in France it is probably no longer possible to create social housing of the spatial quality of those that I was able to plan. The new pedagogies that French society loved a few decades ago, which I was able to magnify through the design of my junior high school suspended from the arcs in Bobigny, are no longer on the agenda. I would have liked to develop my research concerning load-bearing arch structures, which I have already explored through several programs and studies, especially since they respond well to current climate concerns. The most beautiful project is always the one to come. Why not an opera? A museum?

MY FAVOURITE WORK:

The problem is that I don't have one!!! Recent projects like that of Darnétal or the tiny project of Atelier Gold were very little published but, like the others, they deserve attention.

Le Blanc-Mesnil project (3 ha!) and the Collège of Bobigny were published a lot because of their size and wood construction. They are close to Paris. It is impossible to visit the collège - the building is closed now. But Le Blanc-Mesnil can be visited of course.