Dieter Blum

photographer of Marlboro's legendary campaign with cowboy

Germany

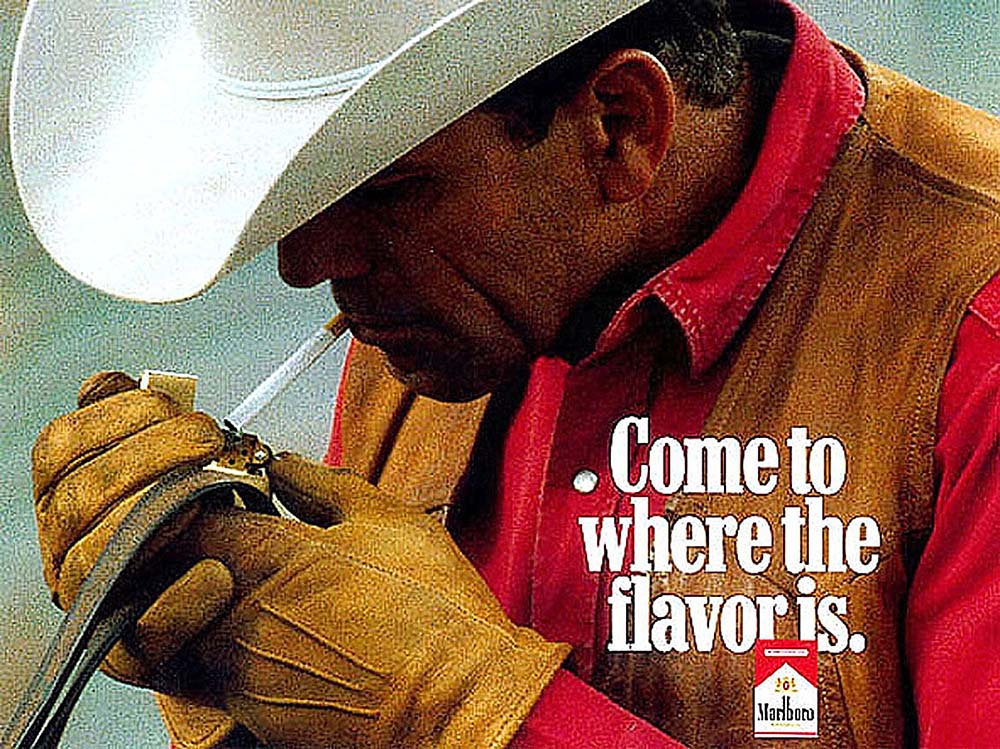

Philip Morris' worldwide Marlboro advertising campaign with cowboys (ran from 1992 to 2004) is legendary and considered an advertising classic. However, hardly anyone knows the name of the photographer: Dieter Blum is the German photo artist who has won more than 150 prizes (including the World Press Photo Award).

Dieter Blum

photographer of Marlboro's legendary campaign with cowboy

Germany

Publications by what a museum director once called "the most famous unknown photographer" (* 6 January 1936, Esslingen/Germany) appeared in TIME, Vanity Fair, Spiegel, Stern and numerous other magazines of international standing. He strongly influenced the product advertising and documentary photography of the time in general by his subjects that cover people, dance, music, travels and art. The work of this self-taught photographer was shown at exhibitions in Tokyo (Kodak Gallery), St. Petersburg (State Russian Museum), Moscow (House of Photography) as well as Venice (Biennale). He has been commissioned by companies such as IBM, Porsche, Shell and has published more than 70 illustrated books - among others on the Berlin Philharmonic/Herbert von Karajan or Vladimir Malakhov, the "dancer of the century" (New York Times). In 2015, Blum was awarded the Médaille Vermeil of the Paris Societé Arts-Sciences-Lettres in Paris for his life's work - as the first photographer in the 100-year history of the society and as one of the very few Germans. Dieter Blum is the father of a daughter and lives with his second wife in Düsseldorf (Germany).

Interview March 2015

More than pressing a button: capturing the magic of the moment!

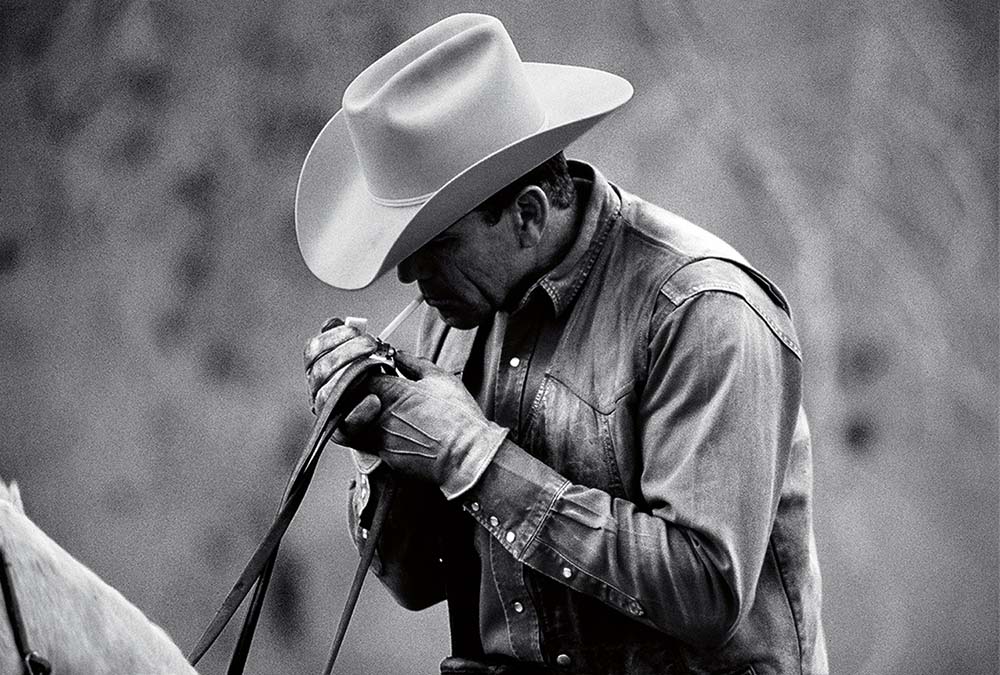

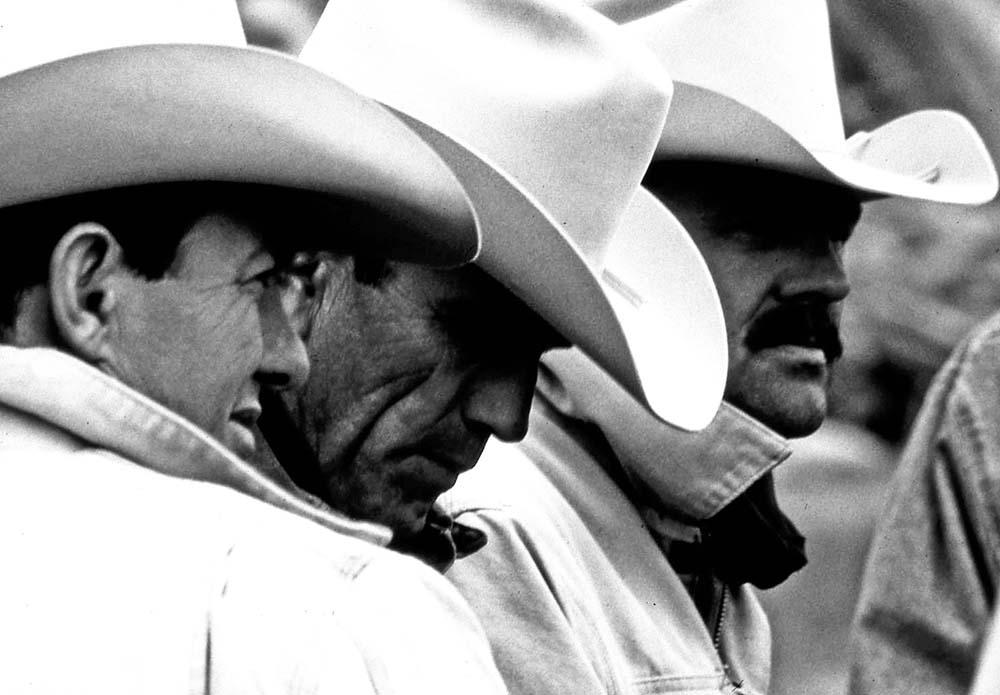

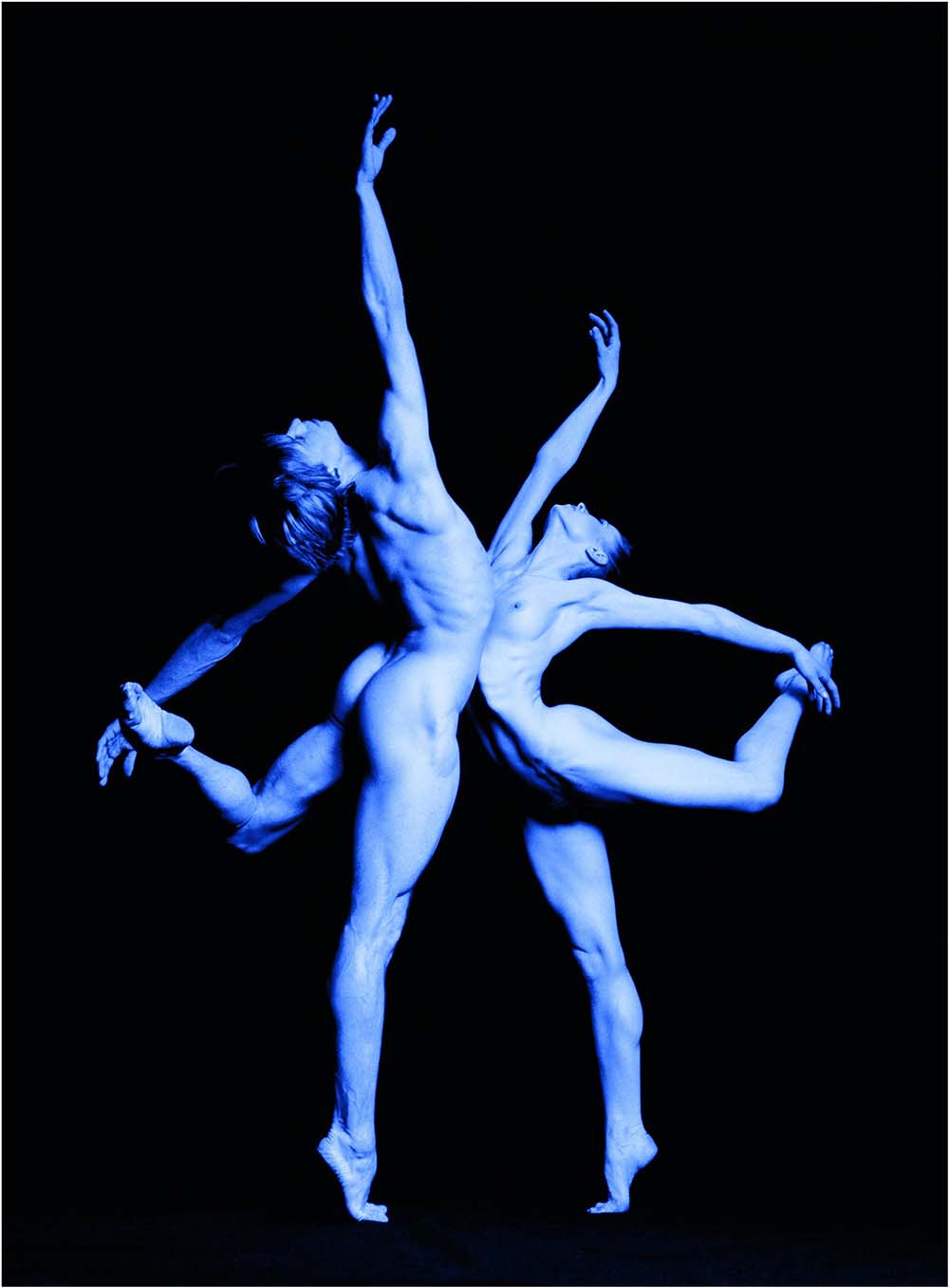

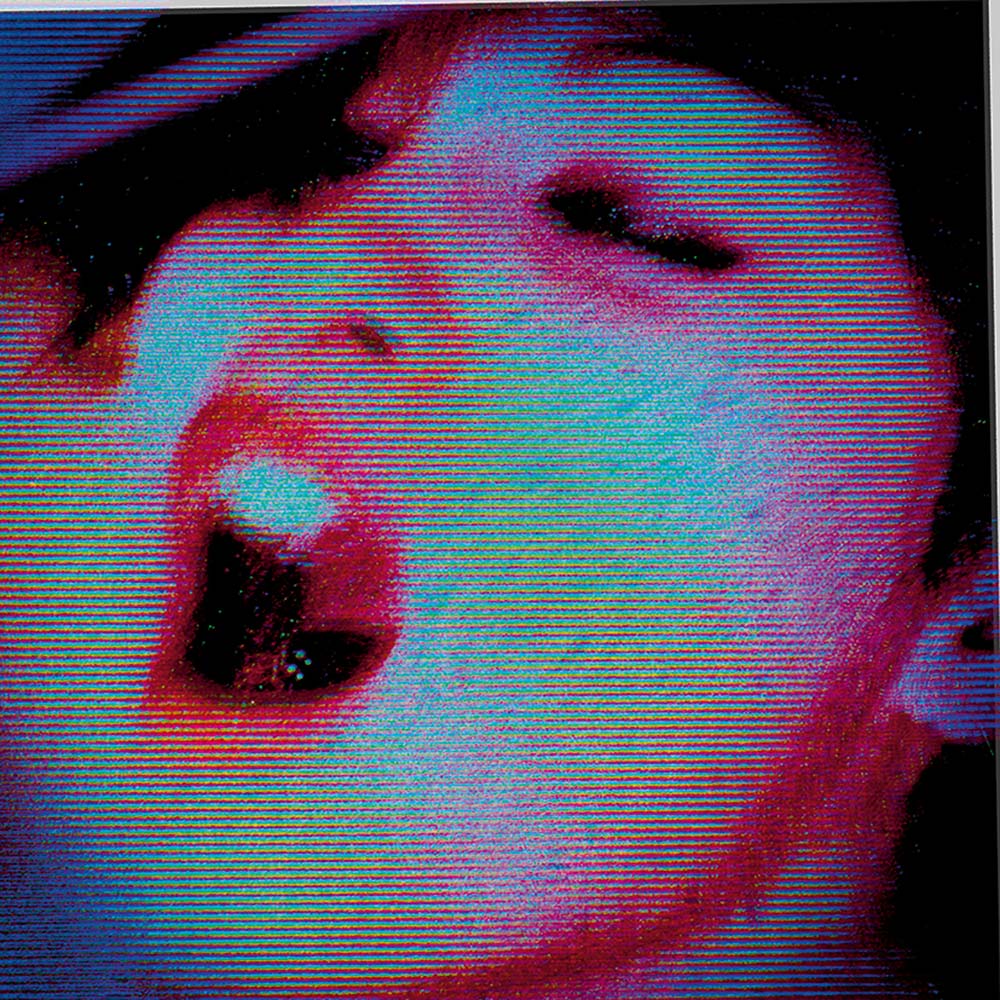

"Intuitions just come, arise and then they are there", Dieter Blum reveals in the exhibition space of a gallery in southern Germany. "For me, this sometimes happens while I'm working. After 15 years of photographing cowboys, the so-called hard men, it almost provoked me to create a counterpart - faces of women at the height of sex." To illustrate, he points to the large-format photo prints from his "Cowboys" and "Coming Soon" series hanging on white walls.

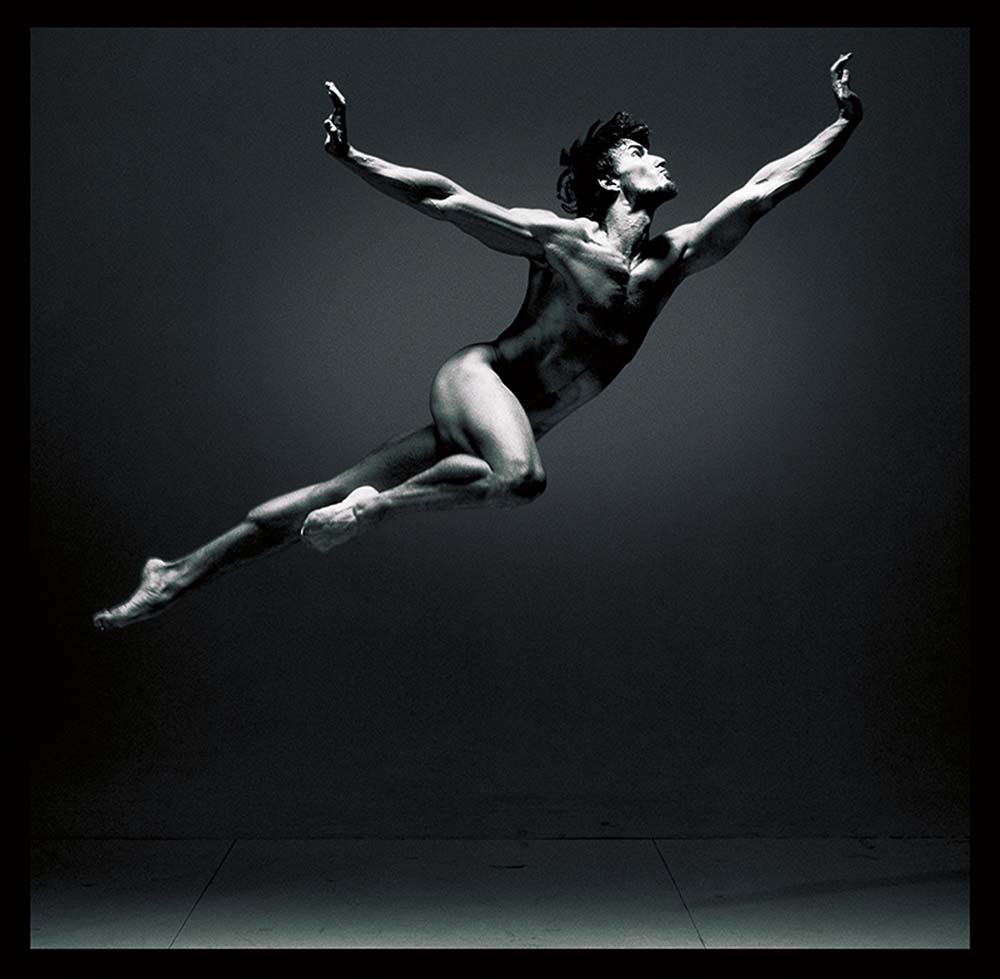

"I usually get the best ideas when I'm asleep and dreaming", the artist, dressed in a dark jacket, scarf, jeans, light shirt and sports shoes, confesses a little later. "Suddenly I'm wide awake and have the idea in my head. I then make notes in shorthand - in the past on pieces of paper, nowadays on my smartphone." An example of this is his nude photo "Michelangelo I". "This is exactly how I had it in my mind's eye and immediately drew it." Before the realisation, Blum showed the sketch to the model, a first-class dancer. He said it was not easy to realise, but tried it anyway. He had to jump stretched out and, because it was impossible to roll on landing, let himself fall with his chest on the screed floor of the studio. The jump took 0.1 seconds. The Hasselblad camera Blum used took 1.8 seconds to wind up. This means that exactly one photo is possible. "The model jumped three times and all three shots are first class. No one in the world has ever taken such a photo! I demanded everything from the dancer and from myself. That's how I got the result the way I wanted it. The magic of the moment is crucial! If it's missing, then something can be technically perfect, but it's also soulless."

The result, by the way, has nothing to do with chance, but "is only feasible due to complete attention and total professionalism". That is why, in addition to intuition, inspiration and creativity, his work also involves craftsmanship. A confirmation of the saying "art comes from skill"? "In photography, you can't learn that at university," Blum emphasises. "Either you are a person who sees really well and can realise it or you are not. You can learn technique and maybe a bit of looking. But nothing more." The Senegalese poet and former head of state Léopold Sédar Senghor attested to the fact that he has a very special eye in the foreword to the illustrated book "Africa". It is a gift that Blum was not born with, "because I have no ancestors with such talent". It was already clear to him at the age of eight that he did not want to take over his parents' textile shop, but to become a photographer.

"I either realise an idea very quickly or it is completely stuck in my mind and will be realised at the next shoot", the professional reports. Photography inspires him to this day because he considers it his hobby. "On the one hand, the creative process is something loose for me. I work as if in a trance, but the encounter between photographer and model takes place at eye level. Sometimes I motivate accordingly or even sketch out how I would like something to look. However, I also leave room for manoeuvre because actors sometimes have super ideas." From this something common emerges. "On the other hand, I have to admit to being a driven person, because I never give in to myself. When I do a project, it has to be down to the last detail for an optimal result. Giving up before that doesn't exist for me!"

Once the shoot is in the can, Dieter Blum immediately looks at the results, makes a first selection. In the case of free works for himself personally, he only takes another look two weeks later and sorts out more than half. "Because I am so merciless towards myself, I throw away everything that doesn't completely satisfy me." This radically reduces the rest. In the end, the shots that remain are those whose expression and message work the way the photographer wants them to. "I can see immediately if there is something really outstanding. I don't let myself be distracted by anything." He is far too critical of his own work to have ever turned in anything mediocre. "And even criticism from others I have always been able to accept." His wife, by the way, is his harshest critic. "Sometimes, though, I stand over it and say I think something is better because I know the photo works from my perspective."

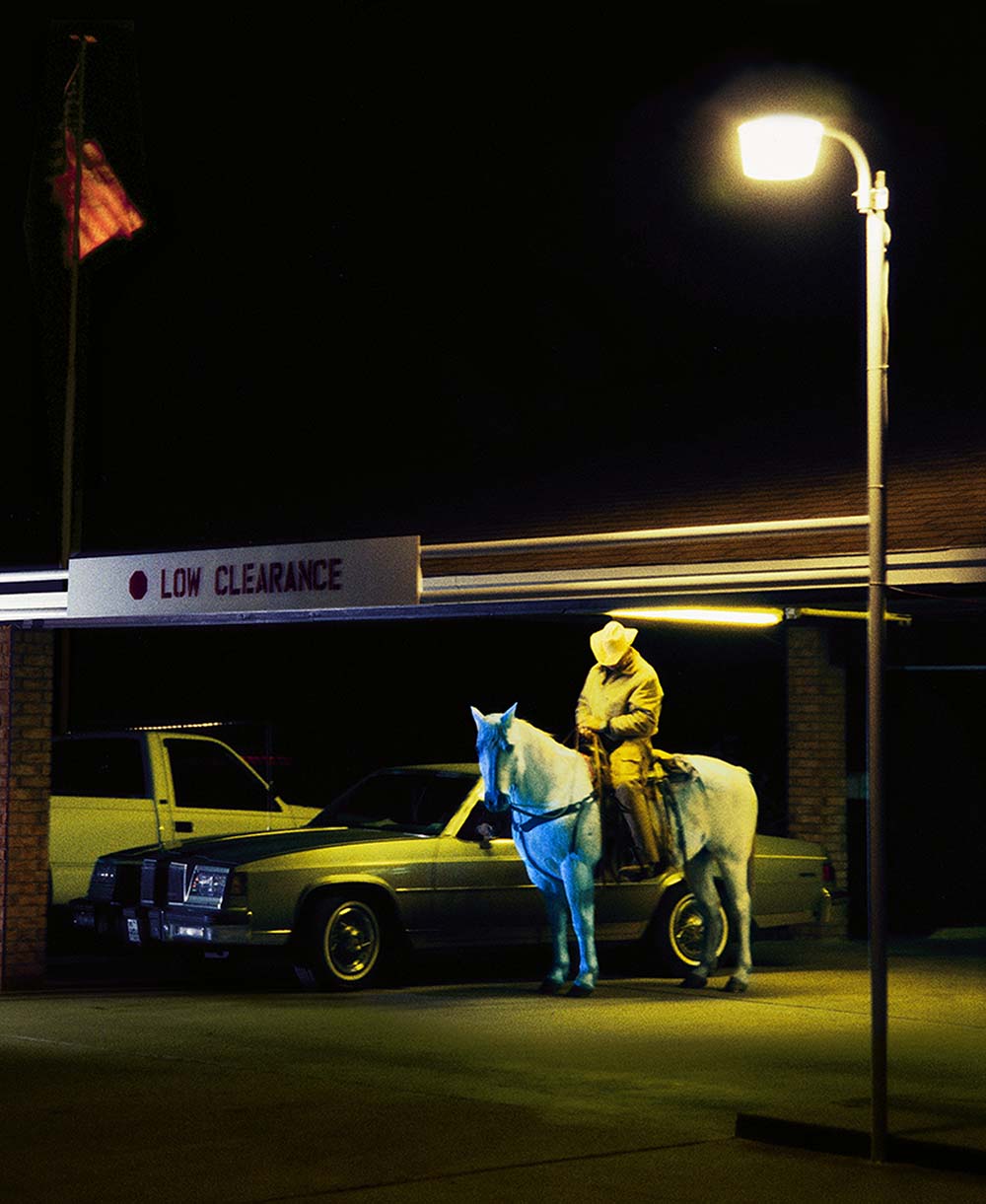

Such a strict standpoint, as Blum has held from the very beginning, does not usually make it easy for a self-employed person. This is exemplified by the assignment that was to establish his worldwide fame and turn his photos into icons. Yet everything could have turned out quite differently, because "I was already very busy at the time in question and I didn't care at all whether I got the job or not." In 1992 he was invited to a test shoot for the global "Marlboro" campaign. Klaus-Erich Küster, creative director of the worldwide advertising agency group "Leo Burnett", told him that he should exclusively realise his own ideas. Blum took this literally: the head of the marketing department was enthusiastic about the photo, bathed in lantern light, of a cowboy sitting on a white horse next to parked cars and designed nine advertisements. "Not one of them was taken, because the clients were completely horrified by my pictures! They said it was a disaster because there was nothing left of the Marlboro idea! I retorted, "I don't see it that way!" Blum's unwavering persistence was to pay off. "Six months later I got the call that they would like my shots after all and I was the only European to get the assignment to photograph their worldwide advertising campaign!" For the mega production in the US state of Utah, the shooting star suddenly even had a helicopter, more than a dozen cowboys, 25 horses, 40 head of cattle, wind machines and lights at his disposal, all transported in 20 trucks.

Why one person makes it and the other doesn't, even though they both have the same skills - Blum doesn't know the answer to that. "One person happens to be lucky enough to slip into something and find someone who supports and promotes him, while others whirl around and can't get their foot on the ground." Even for him, the breakthrough took longer than planned. The reason, he believes, was that people could not pigeonhole him. "When one specialises in one subject, it often works better than when one is active in many fields, as I was. I was guaranteed to be ahead of my time many times! In 1976, I made the big illustrated book "The Africa Book", which set standards and sold 23,000 copies within a year at a price of 200 US dollars. That put me in the "Africa" drawer. But then he turned his attention to Japan ("Nippon"), Russia ("USSR: Voyage of Discovery in a Rich Country"), "Cowboys", The Berlin Philharmonic ("The Orchestra"), dance ("Vladimir Malakhov"). "People couldn't keep up, didn't know which pigeonhole to put me in. That's a problem - but not for me."

Photography has been recognised as art at least since dOCUMENTA 6 in 1977. However, the criteria used to categorise what is art and what is not remain a mystery not only to Dieter Blum. "The American painter and photographer Richard Prince photographed sections of motifs from the Marlboro advertising campaign - including some of mine - and sold these edited reproductions as art. Among them was a very famous picture for which 1.3 million US dollars were paid. However, the original "Rider against a Blue Sky", which came from me, was only second choice for me. That Prince variant is valuable art is probably because the former is pushed by influential galleries." A curious experience in this context was at the Swiss art fair Art Basel 2011, where Blum showed a gallery owner his work - including the aforementioned photo. He was then told that this was too close to Richard Prince. The German photographer replied, "But my work is the original." His counterpart only said, "Nevertheless!".

My personal favourite work

„That's my statement: I just see the motifs immediately. Billy Walck, the head cowboy, once said to me: 'We love you, Dieter, because you have your subject ready in ten to fifteen minutes. The American colleagues almost always need half a day for that. That's just too long, because the facial expressions slip away!“