Miguel Chevalier

pioneer of virtual and digital art

French artist born in Mexico

A pioneer of virtual and digital art. That‘s an appropriate description for this native Mexican, whose impressive works are shown in solo-exhibitions worldwide. „Since the 1980s, the artist has used the computer as a creative medium, continually embracing new technologies — including artificial intelligence. At the same time, his work maintains an ongoing dialogue with art and cultural history. Though rooted in the digital, the sensory experience of his art in the physical space remains an essential element of the man’s practice“ (Kunsthalle Munich). Besides digital images his oeuvre includes holographic imagery as well as „sculptures and drawings realized through 3D printing and robotics, as well as videos and installations. In these generative spatial experiences, algorithms continuously create new images that one can interact with through their movements.“ Very popular are his pixel flowers and „natural history objects, ranging from intricate crystals to striking images of marine life.“ The seeds for these phantastic creations by the man, who calls himself a „digital impressionist“, were sown when he discovered the display items of just a legendary master. All that was true when the later contemporary artist was a child still!

Miguel Chevalier

pioneer of virtual and digital art

French artist born in Mexico

With his father, a university researcher studying the history of Latin America, Miguel Chevalier (* April 22, 1959, in Mexico City) visited museums and palazzos at a very young age. The little boy was deeply impressed by the exhibits of Diego Rivera (1886-1957). The painter and muralist was famous for his large-scale frescos that depicted the Mexican history, cultural and social issues. What the kid couldn’t know back then: the works of prominent painter Frida Kahlo’s husband would have a significant impact on his creative output – at least size and color wise.

Art and artists played an important role at home. His parents were visited regularly by David Alfaro Siqueiro (known for large public murals), Rufino Tamayo (his paintings mix international avant-garde and Mexican sensibilty), surrealistic filmmaker Luis Buñuel (‚Belle de Jour‘, ‚That Obscure Object of Desire‘) or influential architect Luis Barragán.

When his dad becomes manager of the artistic, cultural and academic French school Casa del Velázquez the Chevalier family moves to Madrid. In Spain’s capital the teenager discovers the paintings by Goya, the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns; furthermore the elaborate Spanish Baroque architecture style called Churrigueresque and the Kinetic/Op Art by Carlos Cruz-Diez from Venezuela.

Next stop Paris. Miguel Chevalier joined the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-arts de Paris (School of Fine Arts) in 1978. There the young man learned the basics of drawing and sculpture. Two years after his graduation, he graduated from the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs (School of Decorative Arts) in 1983. In addition a license in art and archeology at the Sorbonne Université plus one in plastic art at its Campus Saint-Charles were obtained.

Having won a scholarship to Pratt Institute, a private university, and the School of Visual Arts, Miguel Chevalier could complete his traning further in New York in 1983/84. At Pratt a computer graphics department was set up already. That was his first contact with drawing software and a graphic interface – the change for him to experiment with these artistic applications. „I quickly realised that digital technology possessed genuine potential and could form the core of a fundamentally innovative artistic approach“, he told art critic/curator Jérôme Sans in an interview. „I felt the urgent need to understand and master ist implications. I was convinced that the avant-gardes had already explored all the possibilities of pictorial creation and that for a young artist to come up with an original statement in that field presented a challenge. My approach was seen as going against the grain of the general trend of restoring painting to the preeminent position it had lost with the conceptual artists of the previous decade.“ What drew him to the field of digital art, Miguel Chevalier adds, „was above all, the observation that artists invariably appropriate the tools of their epoch and, over time, thus become representative of it. I was particularly inspired by artists such as Man Ray, who exploited the full potential of photography with his ‘rayographs’, so elevating the medium to an art form in its own right. Nam June Paik also paved the way for digital art with his videos and installations. He thus became the father of electronic art.“ Considering all that his first solo-exhibition took place in 1987 – created on a Commodore Amiga 1000.

Two years later Miguel Chevalier left for Tokyo to study computer-generated images at Musashino University. In Japan he made his first interactive video work – a piece that was influenced by his visits to Kyoto’s Zen gardens. It initiated the theme of artificlal nature that was going to become recurrent in his work. „I am fascinated by the possibility of navigating between the microcosm and the macrocosm, of exploring the invisible dimensions of life and magnifying them up to a vast scale“, Jérôme Sans quotes him.

The rapid technological developements in the Information Age introducing tools like personal computers, graphic cards, image editing software, color printers, 3D printers and so on widened this adventurous avant-gardist‘s possibilities for new forms of his visual digital art‘s expression enormously.

Miguel Chevalier today creates generative, interactive, and immersive installations that invite viewers to an unique sensory and complentative experience.

La Fabrika is the name of Miguel Chevalier’s studio. There the sought-after lecturer realizes his versatile, often interactive, pictorial virtual language creating a world of colors and patterns pending between the trajectory of the cells, plants/flowers, futurized landscapes and imaginary megacities. The small team is enlarged by scientific researchers or computer scientists when necessary.

His creations are shown around the globe, marrying architecture with contemporary technologies on site if possible. One can get an overview of the works in various books like the 176-pages strong, lavishly illustrated ‚Digital By Nature: The Art Of Miguel Chevalier‘ (Hirmer Verlag) too.

Miguel Chevalier lives in Paris and works close to Paris, in Ivry-sur-Seine.

Interview October 2025

Painting with computers: making the real virtual and the virtual real

INTUITION/IMAGINATION

?: How does intuition present itself to you – in form of a suspicious impression, a spontaneous visualisation or whatever - maybe in dreams?

For me, intuition is like a spark. It can come from an image, a walk in the mountains, sailing on the sea, visiting a museum or an art gallery. It can come from a scientific article or a conversation. It most often manifests itself visually, through the sudden emergence of a shape, colour or movement that flashes through my mind.

For me, creativity lies in connecting different fields, such as the fusion of art, science and technology.

?: Will any ideas be written down immediately and archived?

I always have my phone handy to jot things down or take a few photos. An idea forgotten is often an idea lost.

?: How do you come up with good or extraordinary ideas?

I don't really seek them out. They come through experimentation, observation, leaving things to chance, sometimes at night while dreaming. Curiosity is the main driving force.

?: Do you feel that new creative ideas come as a whole or do you get like a little seed of inspiration that evolves into something else and has to be realized by endless trials and errors in form of constant developments until the final result?

Ideas are born a little like seeds. I develop and refine them over time. I gradually enrich them with my collaborators, who develop custom software for me. Each piece develops organically, like the virtual gardens I create. It is a slow and ongoing process of evolution.

?: What if there is a deadline, but no intuition? Does the first fuel the latter maybe?

So I simply work. Work inspires inspiration. You shouldn't wait for “magic” to happen, you have to make it happen.

INSPIRATION

?: What inspires you and how do you stimulate this special form of imaginativeness?

I draw a great deal of inspiration from my travels, and equally from the natural world.

My childhood in Mexico and my stays in Japan — two countries where nature is ever-present and — have profoundly shaped my lifelong fascination with it.

I’ve always been fascinated by the strange vegetal world — by trees, roots, and leaves, but also by flowers with their endless variations. I’m equally inspired by natural landscapes: the sea and its waves, clouds, snow constantly shifting in form. The sky, light, and natural phenomena such as stars and constellations all awaken in me a sense of wonder — a reflection of the vital energy and invisible forces that animate the universe.

I’m also captivated by all living forms: marine microorganisms like plankton, and coral reefs — organic structures that reveal the intelligence of nature itself. Natural forces such as ocean currents and flows, as well as the mathematical beauty of fractals, are a constant source of inspiration for me. I find endless fascination in their forms, their vitality, their cycles, and their perpetual transformations.

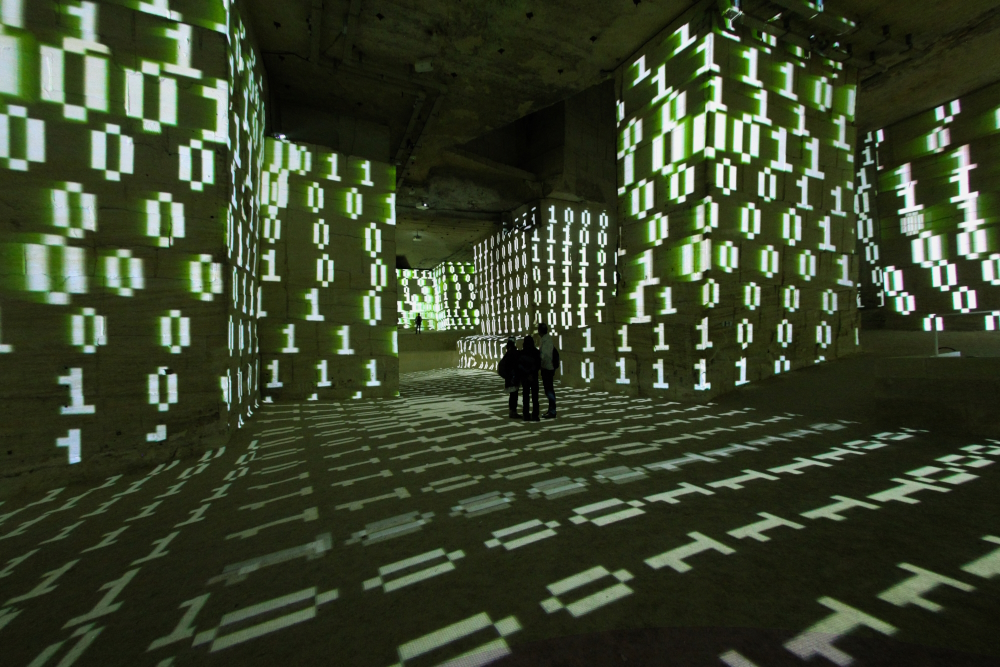

My inspiration also comes from the world that surrounds us and from our contemporary way of life, which is increasingly conditioned by digital culture. Everything that connects humanity and technology fascinates me.

I also find inspiration in science, mathematics, and the beauty of geometric order, as well as in other fields of creation such as architecture and design.

?: How do you filter between ideas that are worthwhile pursuing and bad ones that you just let go of?

I keep the ones that resonate deeply with me, that open up new avenues of exploration. The others, I put aside, sometimes for later.

?: Does an idea need to appeal to you primarily or is its commercial potential an essential factor?

Always please myself first. If I start thinking about the market before creation, I lose the sincerity of my originality and my gesture.

?: Do you revisit old ideas or check what colleagues or competitors are up to at times?

Yes, I sometimes revisit old ideas and see them through the lens of new technologies.

For example, in 1987, I created the work ‘Greenhouse Effect,’ which consists of video monitors inside a greenhouse. The monitors display a looped video sequence that takes viewers on a journey into the organic world. The greenhouse is a metaphorical space that alludes to both the landscape of the modern city and the natural landscape it encloses.

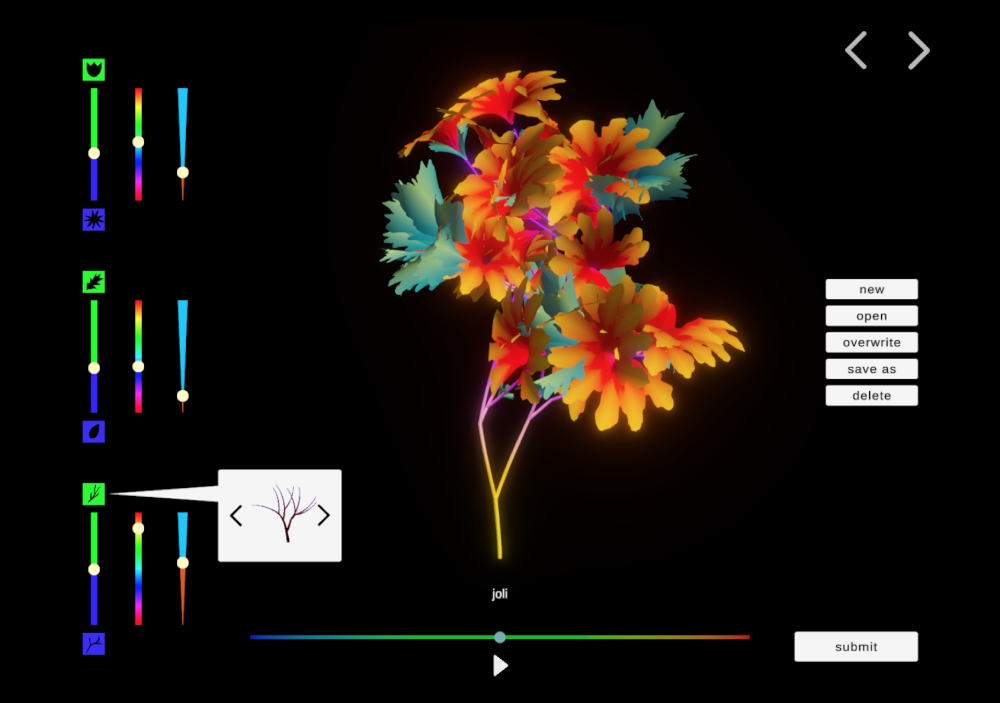

I have revisited the greenhouse theme several times, notably with the work ‘Fractal Flowers in vitro’ presented in 2009 at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris, where virtual flowers from the Fractal Flowers generation grew on the walls of the greenhouse; and most recently in the exhibition "Digital by Nature - The Art of Miguel Chevalier‘ at the Kunsthalle in Munich with the work ’in vitro Pixel Flowers". For the first time, visitors are invited to take part in my largest new virtual herbarium, Pixel Flowers. They can explore infinite variations of shapes and configure a plant on-site through a specific website (https://pixel-flowers.net).

They can then see the ‘Pixel Flowers’ bloom in a small greenhouse, which represents both an artificial space and a symbol of controlled and protected nature.

I also pay close attention to what my contemporaries are doing — not only in digital art, but in design and architecture. I see this observation not as a form of competition, but as a way of remaining connected to the pulse of creation in our time. Their approaches can open new perspectives and stimulate reflection, but I never seek to imitate anyone.

CREATIVITY

?: What time or environment best suits your creative work process — for example, a time and place of tranquility or of pressure?

Especially late at night, when the world calms down. I need both intense periods of interaction with my team to create, but also moments of silence in my studio later in the day.

Which path do you take from theory or idea to creation?

The creation of my works is always the result of a long process of maturation, research, and dialogue between artistic intuition and technology. Designing custom generative and interactive software requires computer skills that go beyond my own. That’s why I have surrounded myself with highly specialized developers such as Cyrille Henry, Claude Micheli, and Antoine Villeret, with whom I’ve been collaborating for many years.

I often draw inspiration from science, nature, and art history. When I have a strong, well-documented idea, I share with my collaborators digital sketches, drawings, and photographs taken from the world around us. Based on this material, we search together for the algorithms capable of bringing my ideas to life visually and dynamically. This requires continuous back-and-forth discussions and adjustments. Developing such a software program from scratch can take two to three years before it becomes fluid and fully operational.

About twenty-five years ago, I founded my own workspace, La Fabrika, in reference to Andy Warhol’s Factory. This studio functions as a true laboratory for research and experimentation, where I can test my works on a large scale before they are exhibited publicly. This collective process does not challenge the role of the artist, I see myself as an energy gatherer, or a conductor, who coordinates different talents to bring a vision to life.

From the very beginning, my software is designed to be reconfigurable, depending on the type of space, museums, art centers, or private collections. For several years, I have also been collaborating with Nicolas Gaudelet from Voxels Productions, whose expertise in technological innovation and IT solutions ensures the design, installation, and maintenance of my works. This network of collaborators allows me to transform ideas into living, ever-evolving digital universes.

?: What’s better in the realization process — for example, speed and forcing creativity by grasping the magic of the moment or a slow, ripening process for implementation and elaboration?

Both. Some ideas strike like lightning, while others need years to ripen and reveal themselves.

?: How important are self-doubt and criticism by others during such a process?

Doubt is necessary; it prevents complacency. Criticism, when justified, helps us move forward.

?: Is it better to be creative on your own, to trust only your own instincts, or to work in a team?

Always as a team. My art is collaborative: I design, but without engineers, coders, technicians and various other areas of expertise, some works would not exist.

?: In case of a creative block or, worse, a real failure, how do you get out of such a hole?

I'm changing the subject; I always work on several topics at the same time. I'm going for a walk. Movement always stimulates thought.

?: Should a creative person always stay true to him- or herself, including taking risks and going against the flow, or must the person, for reasons of commercial survival, make concessions to the demands of the market, the wishes of clients and the audience’s expectations?

You have to stay true to yourself. Markets come and go, but sincere and original ideas remain.

?: How are innovation and improvement possible if you’ve established a distinctive style? Is it good to be ahead of your time, even if you hazard not being understood?

Innovation in art has always been linked to the evolution of technology. In every era, artists have embraced the tools of their time: photography, cinema, video, all of them have expanded the field of artistic expression, even if it took time for these media to be recognized as true art forms.

I was convinced early on that the avant-gardes had already pushed painting to its limits, and that something new had to be invented. Digital technology appeared to me as a new territory for creation, a space where technology could become a poetic language. In the 1980s and 1990s, my work was often misunderstood. As soon as you used computers, people assumed you were dealing with technique, not art. But I persisted. Over time, perseverance paid off, time proved me right.

With the rise of microcomputing and increasing processing power, I was able to create living, generative, interactive works that transform endlessly. These works evolve like artificial organisms, in constant mutation.

To innovate, you must remain curious, alert, and open to change. You have to stay informed, experiment constantly, and push creative boundarie, even if that means being ahead of your time. Being ahead isn’t always comfortable, you’re not immediately understood, but it’s often the price to pay for artistic freedom and genuine creation.

?: When does the time come to end the creative process, to be content and set the final result free? Or is it always a work-in-progress, with an endless possibility of improvement?

Never really. But at some point, you have to let it live its own life, which is why I like generative works. Generativity allows you to create works in real time, capable of evolving infinitely and independently of the artist. By introducing randomness, these creations will generate forms that we could never have imagined. It's a completely new and unique aspect of digital art.

?: How does artificial intelligence change human creativity? And do you? Would will you use it at all?

AI is an exciting new tool that I now incorporate into my creative process. It dramatically amplifies my creations and opens up new perspectives for me.

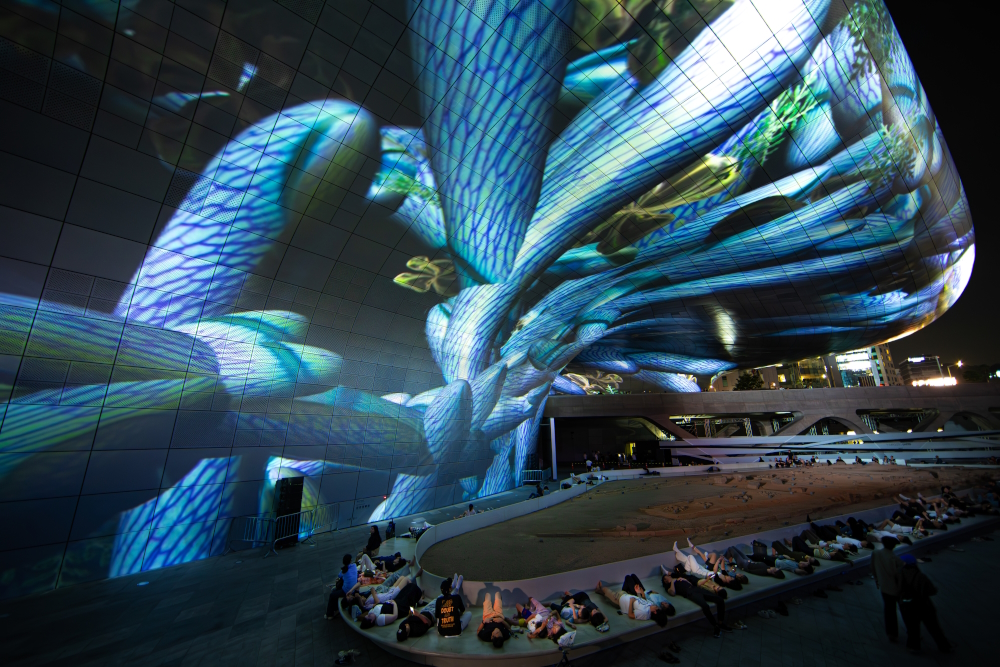

A significant example is the monumental installation ‘Meta-Nature AI’ in Seoul in 2023, projected onto the façade of the DDP building designed by Zaha Hadid. This work marks a decisive step in my exploration of AI.

For this creation, I used AI in an innovative way by compiling a database of images representing plant forms generated by AI algorithms by writing queries called ‘prompts’. These images were produced by AI software, which interpreted my commands to generate new and varied botanical elements of flowers, leaves, fruits, seeds, and tree textures. These images complement the image database I have already created. The visuals generated by AI allow me to exceed my individual creative potential.

AI is nothing more than a tool based on the ‘prompt’ provided by the user. It is important to know how to select the right keywords, organise them and prioritise them in order to obtain results that may be of interest. AI does not kill creativity; it is a powerful tool that can give new forms to artistic expression, provided you have ideas and visions to guide it towards the forms you want to achieve.

Machines will never be able to replace artists, because art is a form of human expression intrinsically linked to imagination, emotions and experience. Machines and artificial intelligence can certainly be used as tools by artists to create works, but they cannot truly replace the artist. Ultimately, it is the artist who conceives and directs the creative process, makes aesthetic decisions and gives meaning to the work. Although AI technologies can facilitate artistic creation and introduce new possibilities, they remain extensions of human creative potential.

SUCCESS

“Success is the ability to go from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm.” Do you agree with Winston Churchill‘s quote?

Yes, I completely agree with what Winston Churchill said.

?: Should or can you resist the temptation to recycle a ‘formula’ you're successful with?

I can extend it, make variations on it, but never repeat it. Each original work must open a new door.

?: Is it desirable to create an ultimate or timeless work? Doesn’t “top of the ladder” bring up the question, “What’s next?” — that is, isn’t such a personal peak “the end”?

We always hope that what we do will last, but I prefer to think about the present. The future will decide.

MY FAVOURITE WORK:

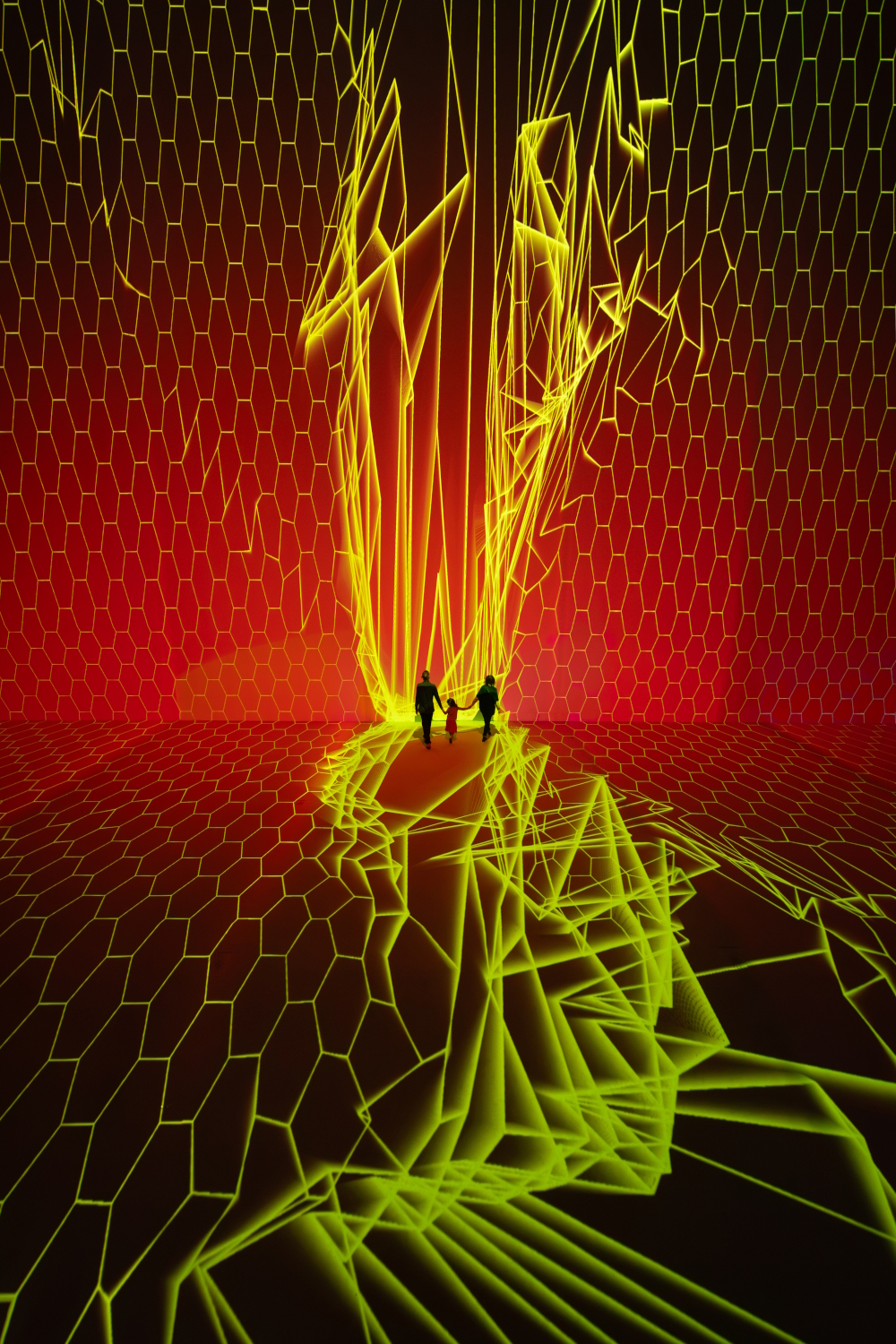

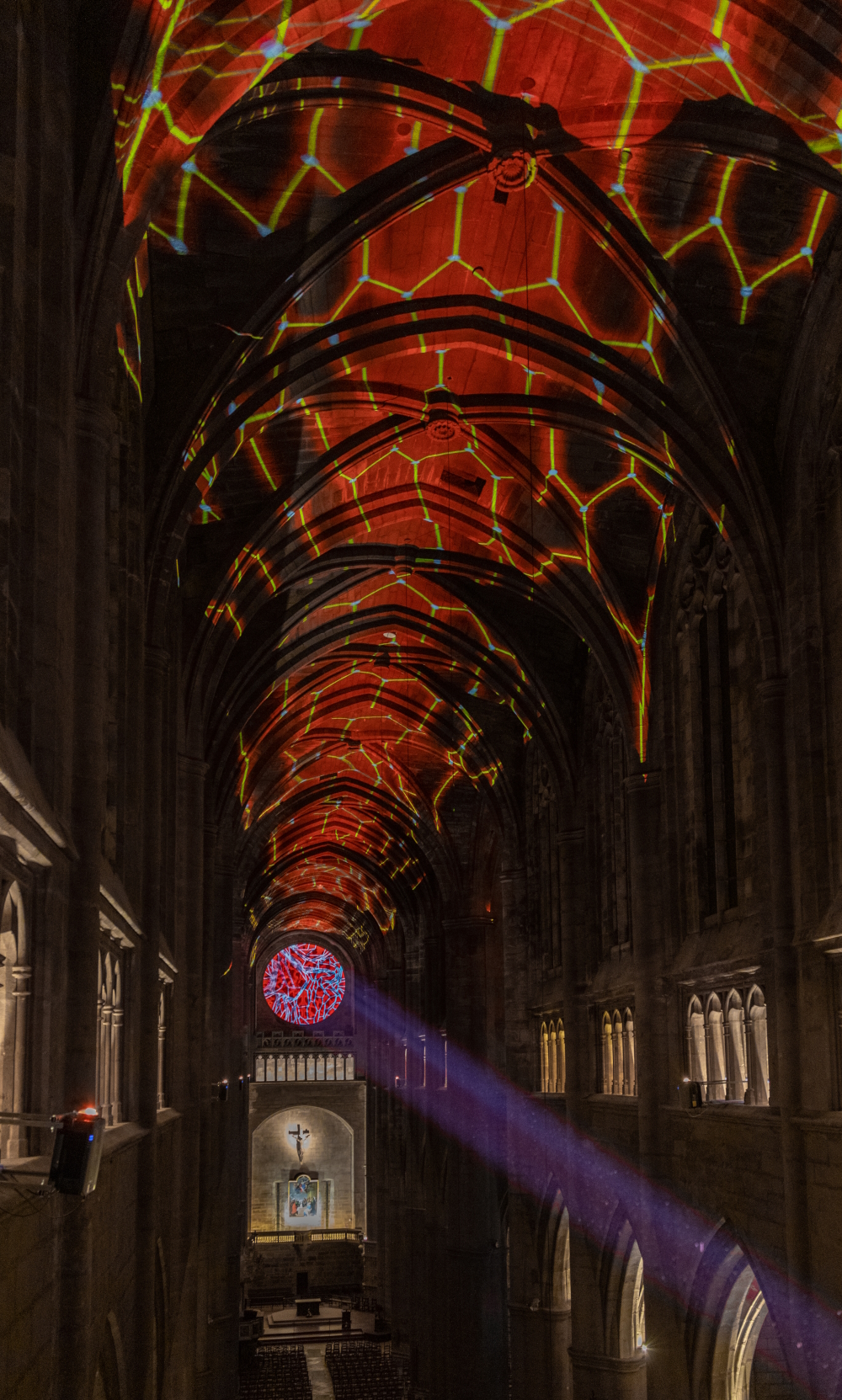

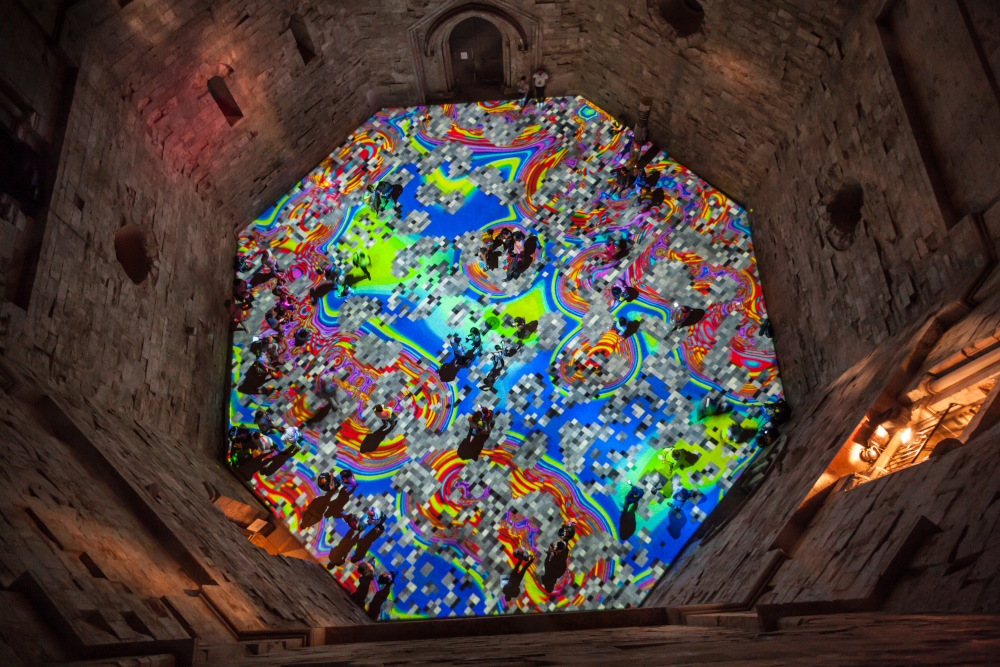

The creation that best represents me would be «Complex Meshes», which also goes by other names such as 'Digital Constellation' or 'Celestial Vaults'. They explore the invisible networks and flows that shape our environment. Through constantly shifting digital patterns, they make visible the intangible structures that govern our world, whether natural, technological or social systems. The viewer is immersed in a universe where the invisible becomes visible.

These generative and interactive works, all designed using software developed specifically for me, are displayed on the floor, walls or ceiling, transforming the architectural space they occupy. They are part of an approach that creates a close dialogue between digital art and architecture, whether in contemporary venues or exceptional heritage sites.

Interaction with the viewer is at the heart of this approach: visitors' movements trigger transformations in the work, modifying the light and digital networks in real time. Each experience becomes unique and evolving. Art ceases to be a static object and becomes a living environment, where the public actively participates in the creation, establishing a strong link between the work, the space and the observer.

This series of works combines sophisticated aesthetics, advanced technology and dialogue with architecture to transform the viewer's perception. The emphasis on invisible flows and networks, combined with the immersive and interactive dimension, makes these creations total experiences, where digital art becomes a vehicle for poetry, contemplation and reflection on our relationship with technology, the systems that structure our world and the heritage that surrounds us.

This is the synthesis of my career: the link between nature, art and technology, a living, poetic and constantly changing universe — like life itself.