Russell Mills

award-winning multimedia artist

UK

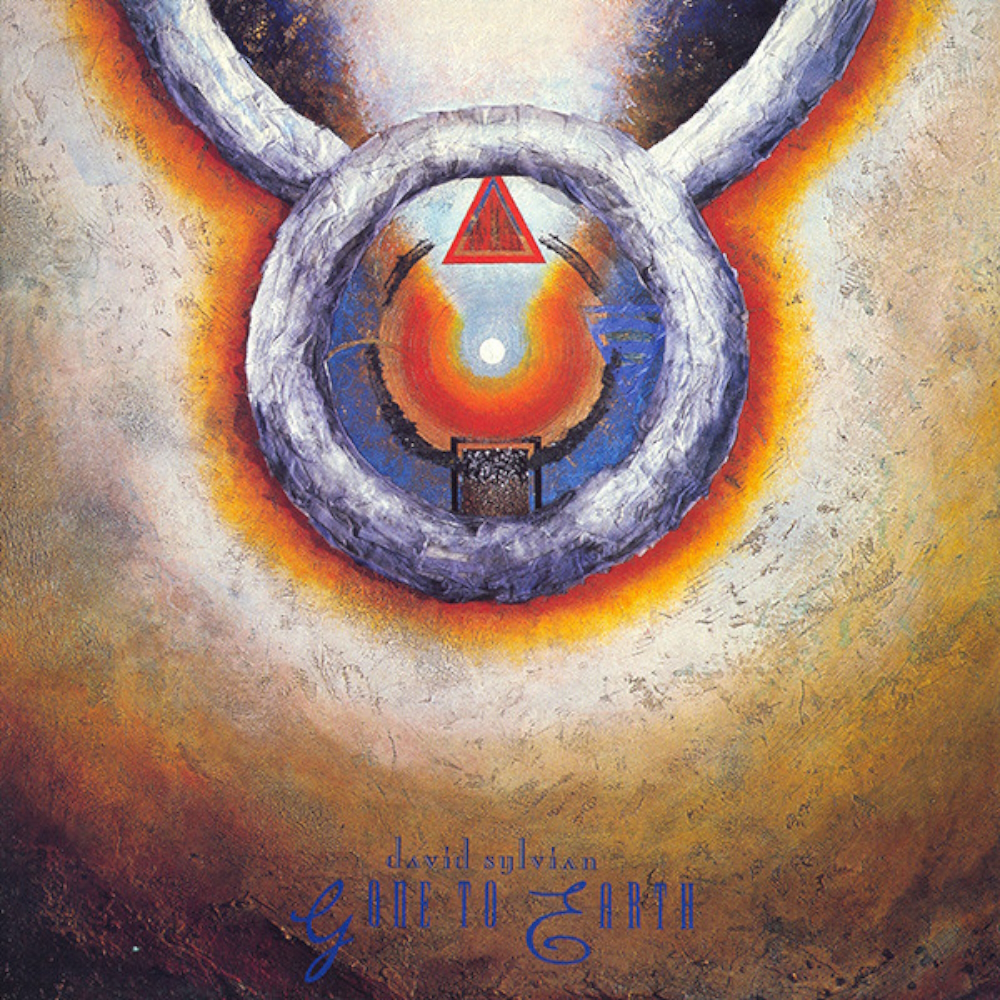

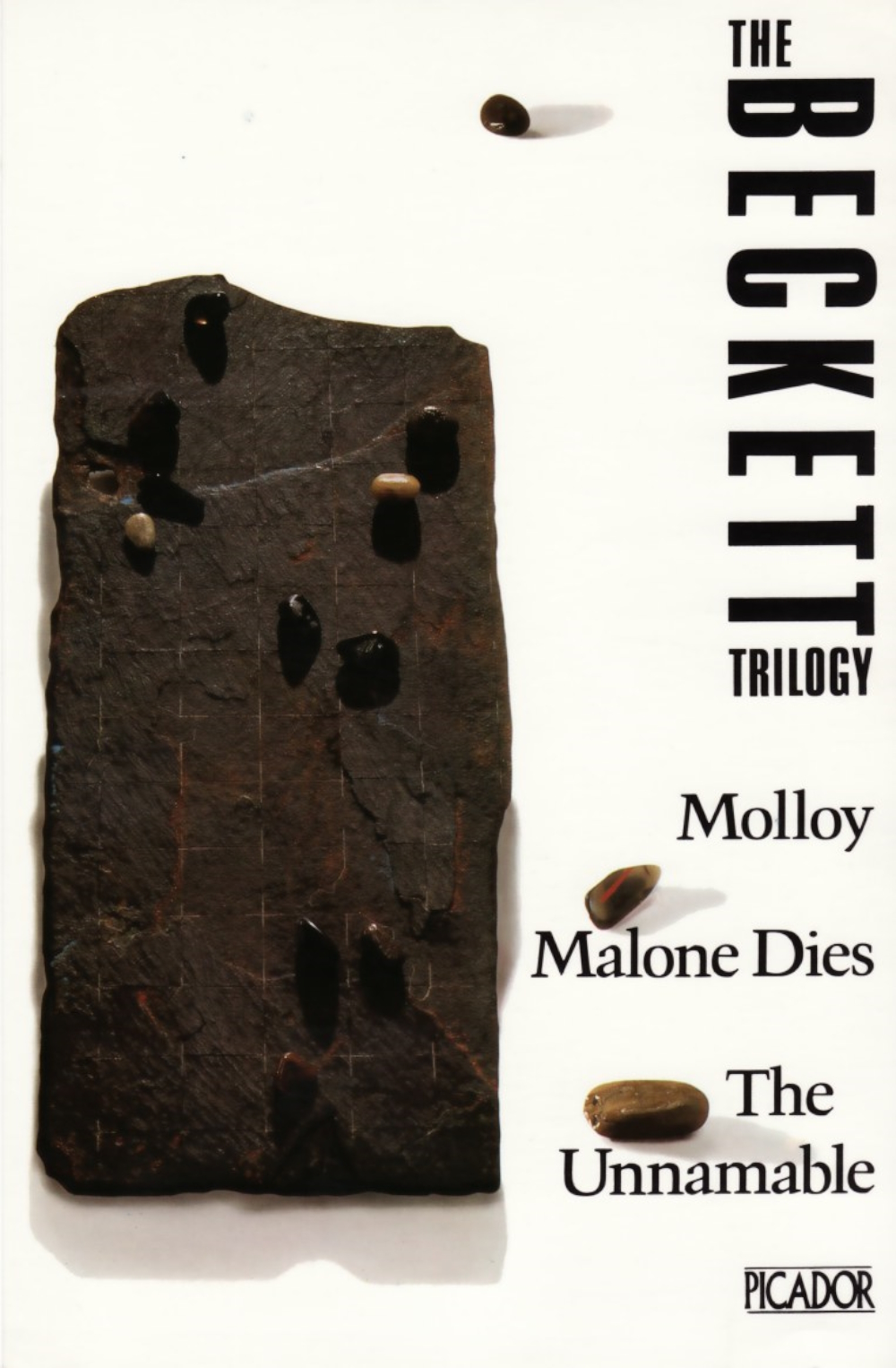

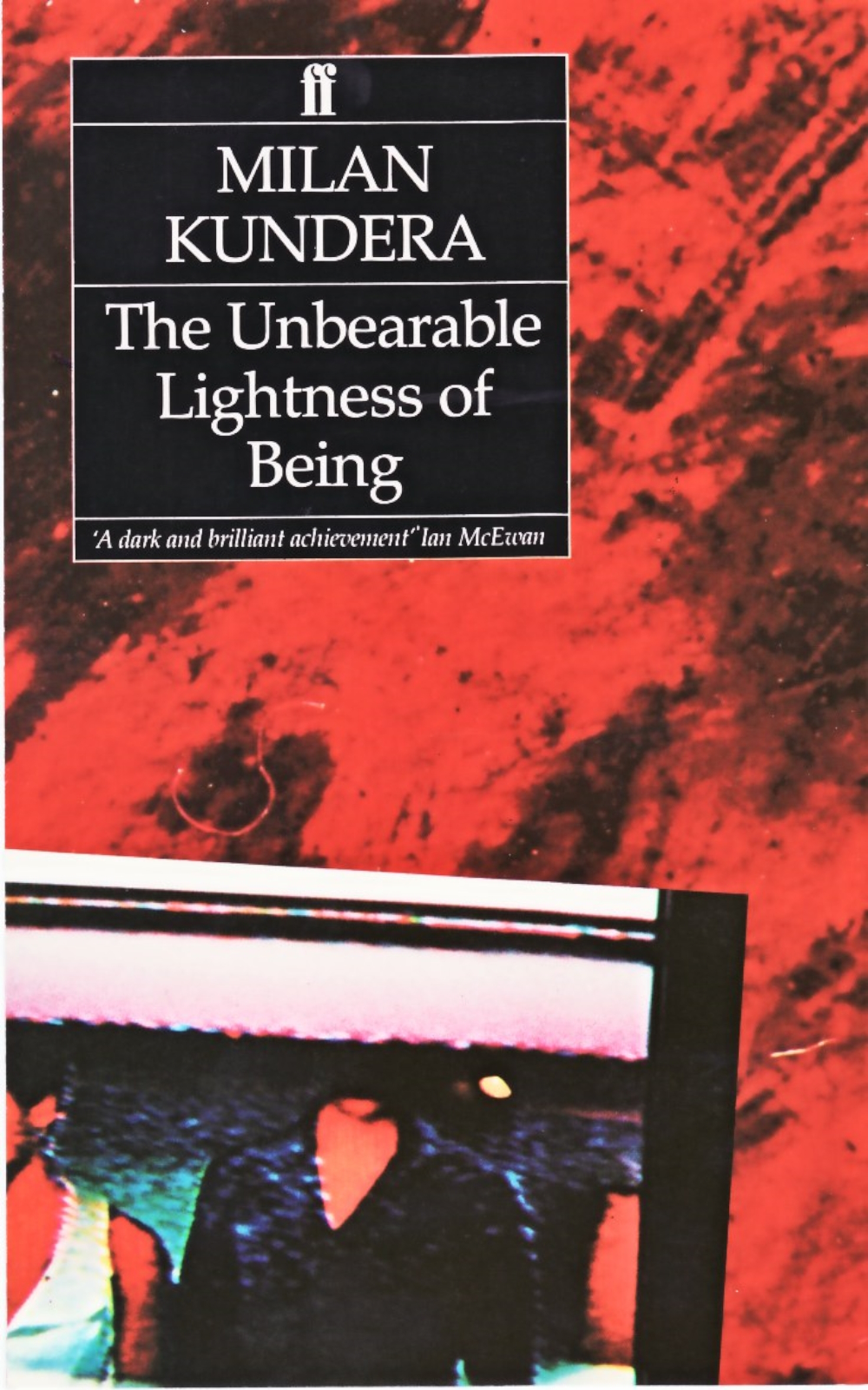

Many of his album covers for the likes of Nine Inch Nails, Peter Gabriel, Brian Eno, David Sylvian and Michael Nyman have won awards and are considered among the most memorable and iconic artworks of their kind. Similarly, book covers that he produced for the UK’s paperback editions of books by Samuel Beckett, Milan Kundera, Ian McEwan and Graham Swift, amongst others, also became hugely influential. A creative who is known for constantly exploring unconventional approaches, this Englishman has always been much more than just one of the most thoughtful designers of recent times. His collaborations with some of the most innovative and influential contemporary creative practitioners have included site-specific, immersive art and sound installations, sonics, stage set/lighting designs, films and performance. Whether commissioned or personal, his work constantly adheres to a reverence to the possibilities of collage. Creating something new out of the juxtaposition of disparate elements is, according to his statement on innerviews.org, “the most important and most influential cultural idea to have emerged in the 20th century.“

Russell Mills

award-winning multimedia artist

UK

Do not let yourself be captured by the system, but go your own way! The career of Russell Mills (b. 1952 in Ripon, Yorkshire) demonstrates that he‘s followed such a credo unfailingly throughout. It began in the late 1960s with a year of Foundation studies at the Canterbury College of Art, followed by three years studying for BA at Maidstone College of Art. As the youngest of two sons of a Royal Air Force officer, he didn’t particularly agree with his tutors’ ideas ,and consequently spent most of his time experimenting with mixed media in the printmaking department. Wishing to move on to an MA course, Mr. Mills considered applying to the Fine Art department at The Royal College of Art (RCA) in London “the world’s most influential postgraduate institution of art and design“ (university‘s website), but found it too insular. Having wandered across the corridor from the Painting studios, Mills discovered a world of experimentation thriving in the MA Illustration department and decided its ambience was far more preferable. After three years there he received the Berger Award at the RCA for the Best Degree Exhibition in 1977!

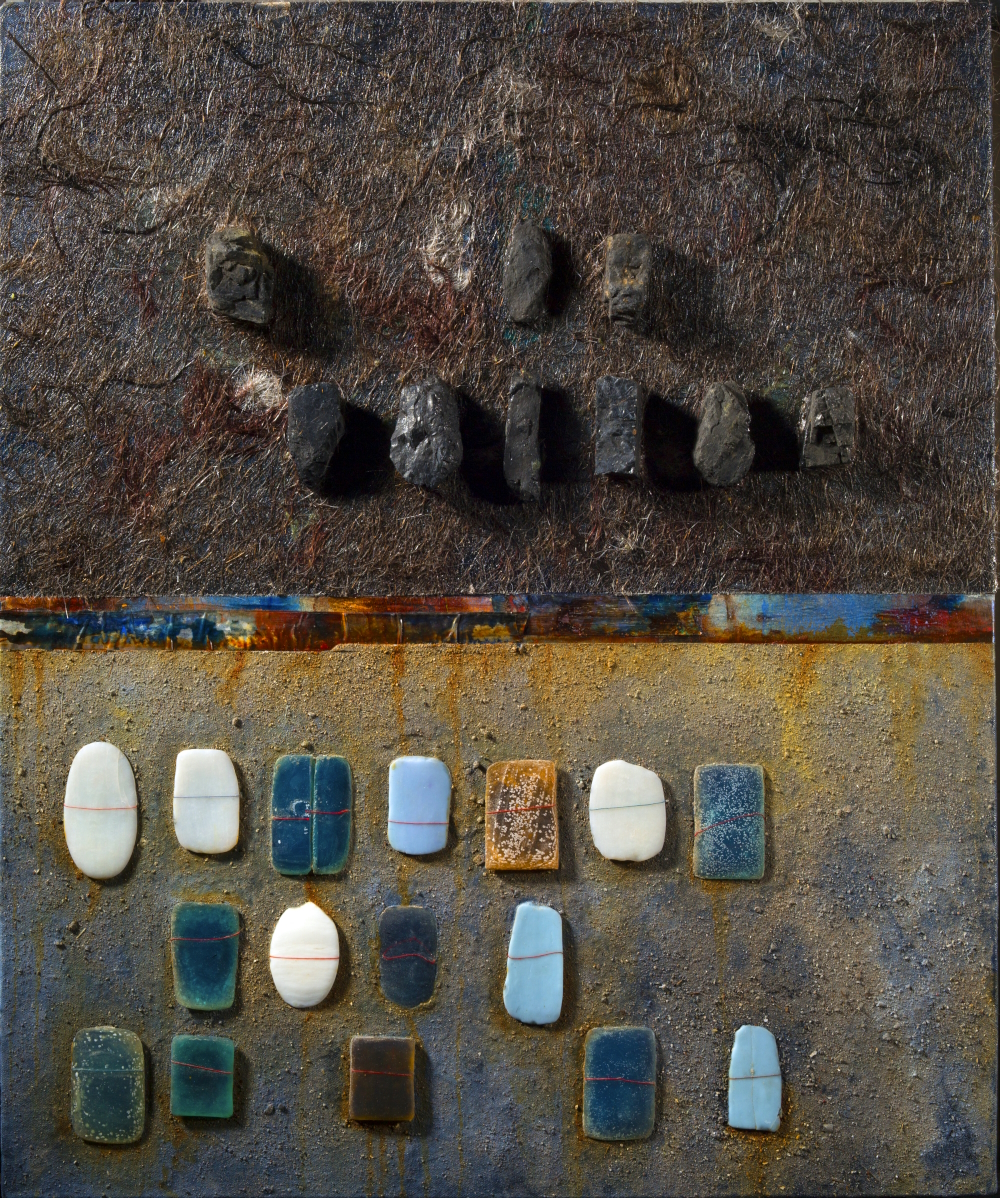

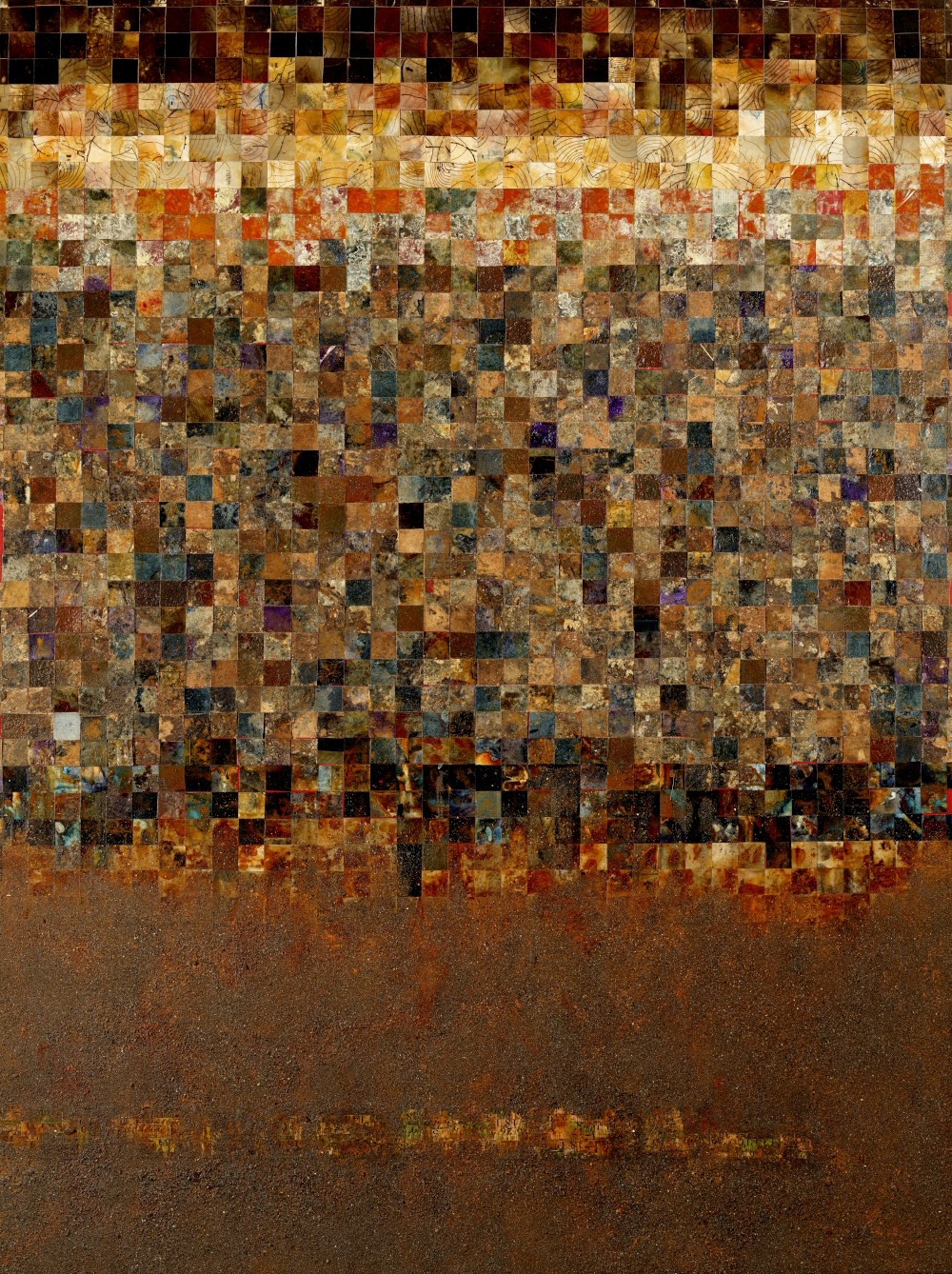

“In the 1980s“, Wikipedia states, “Mills began receiving commissions to design record album covers and associated packaging. Stylistically, his work at this time became much more abstract, abandoning figurative representation in favour of symbolic allusions. He regularly treated the canvas as a sculptural plane, with materials such as metals, powders, bones, feathers, beeswax, fabric, wires, animal skins and papers embedded in thick paints and pastes. Works of this period generally occupy the entirety of the canvas with little or no ‚negative space‘ left. [...] From the later 1990s to the present, Mills' work has again evolved to a new style, made possible by the advent of computer design applications such as Photoshop. The ‘collage‘ aesthetic is still frequently seen, but now in a virtual/digital form, with many abutting and overlapping semi-transparent images, often cropped into crisp, aligned rectangles. Mills still uses hand-drawn or -painted imagery, but as often as not it is scanned into the computer and treated as another malleable collage element. Images of water and sky are frequently seen, and a cooler colour palette often prevails (in contrast to an earlier reliance on earth tones).“

“Among his formative influences, Mills cites the proto-conceptual art of Marcel Duchamp and the Dada and Surrealist collages of Kurt Schwitters and Max Ernst“, noted the graphic design journal Eye. “He also acknowledges direct debts to contemporary artists such as Anselm Kiefer and Antoni Tàpies, two masters at manipulating unconventional materials, and would therefore seem to have an honourable pedigree for a painter working at the tail-end of the century of Modernism.“

Collage has also underpinned his ongoing musical project, Undark. Prior to recording the album Pearl + Umbra, Mills asked many of the musicians he’d worked with and for to contribute sound samples - melodies, rhythms, vocals, anything they wanted - with no prescribed notions of how they might have been used. With a rich palette of diverse sound samples, Mills weaved the elements, seamlessly merging them into diverse, blissfully uncategorizable pieces ranging from the flowing to the fractured.

“I am interested in texture, both in my visual work and in my soundworks (installations and Undark tracks)“, he told sylvianvista.com. “I work in layers, conceptually and physically. Ideas are layered and stripped away, other ideas added, and stripped away, and so it goes on, concealing and revealing.The same happens with the actual materials that I use [through] the use of chemicals and unpredictable processes, previously unimagined textures can emerge. The revealing of the previously unknown is both transformative and stimulating.“ During the interview Mills realised what he’d really been doing all this time: “I discovered that there have been a few conceptual threads that have been consistently tying all this work together. What became evident to me was the most important ideas, those central to my thinking and the various ways of making work (visual and sonic) involve contingency and its natural kindred spirit, collage. By contingency I take to mean one action creates a reaction, which creates another, which creates another, ad infinitum.“ A quote from iloveoffset.com sums it all up: “Russell describes his working process as “serious play”. Believing that artists are obliged to explore new ways of working and thinking in order to understand the world, experimenting is at the core of his work.“

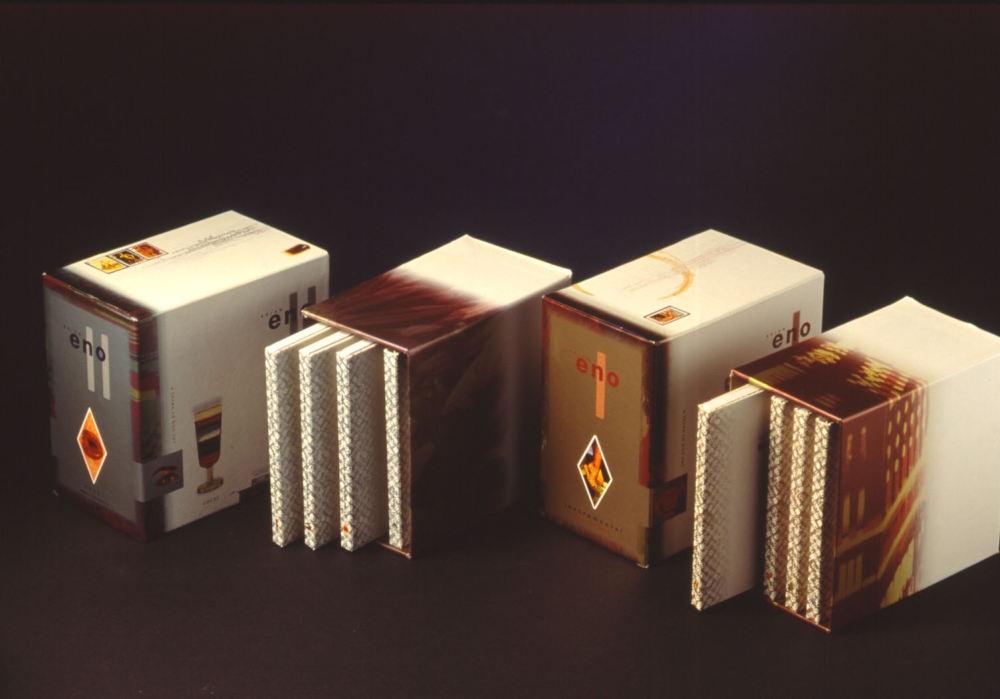

This renowned multimedia artist has produced works for the likes of The Royal Shakespeare Company, Toshiba, Amnesty International, War Child, The British Council and more, has won numerous awards (including a Grammy Nomination for Brian Eno I & II CD Box sets in 1994). He exhibits his works worldwide, has published various extraordinary books such as the limited edition series of Still Moves books each carrying two CDs charting his multimedia installations from 1994 to the present. From the early 1980s Mills returned to the Royal College of Art as A Visiting Tutor, a position he held until 2013.

Russell Mills is based in Ambleside, Cumbria (UK), where he lives just doors from Kurt Schwitters’ last home.

Interview June 2023

The art of collage: an assemblage of disparate items reveals previously unknown possibilities and alternative readings

INTUITION/IMAGINATION

?: How does intuition present itself to you – in form of a suspicious impression, a spontaneous visualisation or whatever - maybe in dreams?

Intuition comes from experience, shaped through and by years of accumulated learning, looking, reading, researching, thinking and doing. For me, intuition isn’t manifested in any definite form. It usually reveals itself gradually and incrementally, with small ideas or inspirations leading to other ideas, many initially being apparently irrelevant. Ideas tend to present themselves to me in fragmentary forms and can come from anywhere: a word on a page, a phrase in a novel or poem, a piece of music or a scene from a film that moves me, an overheard comment, a news report that draws anger or perplexity, an everyday encounter chanced upon in a street. When I notice and take note of these disparate ideas I rarely have a clear idea of whether they will be of any use or relevance to my work, they just seem, in the moment, to strike a chord. I’m a great believer in Louis Pasteur’s axiom, “Chance favours the prepared observer”, and naturally try to stay alert for any possible stimuli that might have a correspondence with my work. However, whether I’m able to log them or not when they present themselves entirely depends on how sharp my acuity happens to be.

?: Will any ideas be written down immediately and archived?

I am an obsessive note-taker, constantly writing down ideas in several totally disorganised notebooks or on any bits of paper I happen to have at hand. Every so often I review these fragments and may transfer some of the ideas to a more, theoretically, formal file i.e. a pile of loose A4 sheets of 5mm graph paper, which inevitably gets shuffled around so much that there is no chronology to follow and indeed no coherent order to them. This is the extent of my archiving, if it can be called that. My research is equally haphazard.

?: How do you come up with good or extraordinary ideas?

I’m not sure I do actually “come up with good or extraordinary ideas”, although of course I do strive to develop ideas that I think are of worth and interest. Primarily they must excite me, artistically and conceptually, and ideally they should carry or suggest, obliquely and metaphorically, some moral imperative.

I adhere to John Ruskin’s recommendation for close observation, ‘imagination by combination’ and ‘accidental association’, and I’m guided by Thomas Aquinas’s axiom that we should “operate according to Nature in the manner of her operations” i.e. follow the nature of Nature. My work is analogous to the ceaseless flux of nature’s generative processes, and explores ideas about the natural world as matter, as force, as school, as metaphor for transformation, and as being profoundly political and economic. Visually and sonically my work is primarily inspired and informed by ideas of contingency, chaos and order, control and surrender. Contextually anchored and process-driven, they evolve through a reciprocal exchange between the ideas and the physical processes, which I instigate to encourage chance and indeterminate results. Each, in varying degrees, influences the other. As diverse matter is either broken down into entropic confusion or necessarily arranges itself into a cohesive whole, the processes celebrate the phenomenal weave of order and chaos of the natural world, while also examining our abiding obsession to control and exploit both its human and natural resources. From such a vast ocean of information, I’m never short of ideas and potential subjects to explore.

?: Do you feel that new creative ideas come as a whole or do you get like a little seed of inspiration that evolves into something else and has to be realized by endless trials and errors in form of constant developments until the final result?

I enjoy complexity and ambiguity, and my thought processes are associative. Works generally begin with a tiny spark, an idea that intrigues me, which leads to other, sometimes apparently unconnected ideas. I tend to create a kind of entangled cat’s cradle of multiple ideas that are threaded together but with no obvious logical correspondences. My work proceeds, necessarily, via multiple trials and errors. – these are part of the work.

I think my approach can be best described in the words of one of my favourite writers, Samuel Beckett, in a memorable interview with Tom Driver (Columbia University Forum) in 1961, in which he considers the world as being in a state of “buzzing confusion”, observing that:

…there will be a new form, and that this form will be of such a type that it admits the chaos and does not try to say that the chaos is really something else. The form and the chaos remain separate. The latter is not reduced to the former. That is why the form itself becomes a preoccupation, because it exists as a problem separate from the material it accommodates. To find a form that accommodates the mess, that is the task of the artist now.

?: What if there is a deadline, but no intuition? Does the first fuel the latter maybe?

I very rarely have to work to deadlines these days, but when obliged to do so I find them perversely inspiring. They force me to short circuit my thinking, to pare down my options, to bypass what the Buddhists call the ‘Mire of Options’ that can bog me down when I’m working with no external pressures or obligations.

INSPIRATION

?: What inspires you and how do you stimulate this special form of imaginativeness?

As alluded to before, I’m primarily inspired and informed by ideas about the contingency of the largely unseen and unheard processes of the natural world and of our own existence in the everyday. As in the natural world, any moment of our chaotic lives might have had a different content, every aspect of our existence, from birth onwards, is absolutely contingent, and most are seemingly devoid of necessity. How to make sense of the paradoxically chaotic order of earthly phenomena, human and otherwise? Strive to exert some control of it ,or surrender to it?

I work with organic and traditional materials in admixture with volatile chemicals and unstable solutions, which, being susceptible to atmospheric changes, set off indeterminate and transformational processes that are determined by the unpredictable effects of evaporation, sedimentation, crystallization, and of time itself. The works evolve in causal nexus, which are contingent and continually shifting. A small change in the early stages of an unpredictable sequence of events produces larger effects in the later stages. Every change effects and is affected by others operating consistently upon it, with it, and through it. Documenting the history of their own changes, the works metamorphose into new images, previously unimagined, always unexpected and full of potential. Edward Lorenz’s chaos theory metaphor is well known: a butterfly flaps its wings in Brazil, producing a storm in Texas: this is contingency.

The American palaeontologist, evolutionary biologist and historian of science, Stephen Jay Gould, in his Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History, sums up contingency thus:

I am not speaking of randomness, but of the central principle of all history - contingency. A historical explanation does not rest on direct deductions from laws of nature, but on an unpredictable sequence of antecedent states, where any major change in any step of the sequence would have altered the final result. This final result is therefore dependent, or contingent, upon everything that came before -the unerasable and determining signature of history.

As another of my touchstones, the poet Seamus Heaney observed, “Anything can happen.” The uncertainty, of our past and the unpredictability of our future, caused by contingency - the cornerstone of reality, the nature of nature - is what makes this such a challenging idea, particularly in these increasingly anxious and increasingly accelerating times. In our quest to better understand and control the workings of the world we devise more ways of quantifying and measuring everything - from economic growth to the air we breathe, from our national wealth to our wellbeing, from the Internet to the ideas we think. However surveys, analytics and spreadsheets ignore context, ambiguity and idiosyncrasy. Designed using rigid parameters to collect a narrow range of prescribed data in order to reach a finite set of outcomes, many are used to indicate alternative means with which to implement control over events, conditions or people. Indicators at best, merely promoting unifying generalities, they tell only a small part of a story. Most ignore that we, our everyday dealings with the world, and the phenomenal world itself, are made up of a gloriously unruly and amorphous mash-up of complex and nuanced variables, making every moment and us unique. Capricious happenstance and inner worlds of feeling and sensation are absent from such reductive methods. It is this dichotomy between the transformative happenstance of reality and our ceaseless drive to grid and graph the world in order to understand, control and exploit it, that inspires my work.

Discovery requires aesthetically motivated curiosity, not logic. For new things can acquire validity only by interaction in an environment that has yet to be. Their origin is unpredictable.

-Cyril Stanley Smith, On Art, Invention, and Technology, Boston, Technology Review, (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1976)

?: How do you filter between ideas that are worthwhile pursuing and bad ones that you just let go of?

Filtering the good ideas from the bad is a granular process. As works proceed with ideas hopefully, juxtaposing into some kind of coherence (for me anyhow), any weak, unconvincing ideas are discarded, or if there is a seed of potential in them, filed in my brain for possible future use.

?: Does an idea need to appeal to you primarily or is its commercial potential an essential factor?

I work for myself, so obviously the ideas and the works have to appeal to me before any other considerations. The work is not made for an audience, but of course I hope that others will like what I do, or be intrigued enough to look closer and to ask more questions.

?: Do you revisit old ideas or check what colleagues or competitors are up to at times?

I do revisit old ideas, but only when I feel they may be relevant or useful to whatever I happen to be working on the present. Just because an idea is old doesn’t make it invalid or irrelevant. Sometimes the old ideas (in every aspect of life) are simply the best.

While I’m aware of what is happening in the art world, I don’t religiously follow its vagaries and have no interest whatsoever in who or what is being vaunted as the next ‘big thing’. I’ve been suspicious of the art world for decades since it jettisoned its cultural values in favour of becoming a money-driven activity, a corporate vampire sucking the life out of authenticity to satisfy the aspirations of these affluent and usually vacuous wide boys desperate to acquire some the sheen of cultural respectability. I don’t really consider other artists as colleagues and certainly don’t see any as being competitors. Rather, there are some who I regard more as fellow-travellers, albeit travelling in different vehicles, so to speak. I revere and constantly go back the works of Kurt Schwitters (my ultimate artist hero), Antoni Tapies, Alberto Burri, Joseph Beuys, Jannis Kounellis, Robert Rauschenberg, and Anselm Kiefer, to both stimulate me and to confirm my thoughts and beliefs. Others, contemporary artists, whose work I admire greatly are Tacita Dean, Theaster Gates, Olafur Eliason, Susan Hiller, Jeremy Deller, Cornelia Parker, Doris Slacedo, and Katie Paterson, to name but a few. Of course, there are also many writers, musicians, film makers, philosophers, thinkers and activists who inspire and inform how I think and work.

CREATIVITY

?: What time or environment best suits your creative work process — for example, a time and place of tranquility or of pressure? Which path do you take from theory or idea to creation?

I prefer working alone in my studio, fully immersed in the work. I need a certain amount of solitude, although I enjoy the potential of working collaboratively with others, especially when I’m working on creating a new multi-media installation.

As mentioned above, the works emerge from the juxtaposition of ideas and processes. Ideas suggest processes, which in turn suggest other ideas; the whole journey proceeds as a kind of pinballing from idea to process to idea, and on, until the work is, hopefully, realised.

?: What’s better in the realization process — for example, speed and forcing creativity by grasping the magic of the moment or a slow, ripening process for implementation and elaboration?

The nature of my work requires both. The pressures of working with materials and solutions, such as chemicals, in unlikely and wholly unscientific admixtures, demands different reactions to what is (or isn’t) happening. When the reactions of chemical processes are fast then my response has to be swift enough to capture and seal the results. Alternatively, when some processes are necessarily more gradual, then I have to be far more patient and must resist tampering with what’s happening.

?: Do you have any specific strategies you use when you're feeling stuck creatively?

Unfortunately, there is no sure-fire silver bullet for the mental block. When I do have one, which is often, I have to first persuade myself not to panic and to step back from the problems. Sometimes this entails ignoring them entirely and doing something else, something completely different. Even doing something as apparently mindless as the washing up can open up ideas that might help. As the mind wanders it finds new connections. Otherwise, I simply nag at the ideas, perhaps considering them from other perspectives. My approach is a bit like climbing a mountain via different routes, taking detours so as to not reach the top as quickly as possible, in the hope of discovering previously unknown surprises. Eventually there comes a moment when something clicks, a connection is made and a key unlocks the door.

?: How important are self-doubt and criticism by others during such a process?

I’ve always experienced plenty of self-doubt. Any artist who claims not to suffer any self-doubt is probably not a very good artist. I think it’s essential to be continually questioning the work, its value and its authenticity. I also welcome the constructive criticism of others. To hear other viewpoints or to see through others’ eyes can enable a new or renewed clarity in one’s thinking. As for most of the time I work alone, I therefore have no choice but to trust my own instincts. However, as I’ve stated, I enjoy working collaboratively, in making installations and music for instance. Working with others whose backgrounds, skills, and ideas are different from mine is always enriching and can lead to new ways of thinking, looking and making.

?: Should a creative person always stay true to him- or herself, including taking risks and going against the flow, or must the person, for reasons of commercial survival, make concessions to the demands of the market, the wishes of clients and the audience’s expectations?

Yes, I believe that an artist should remain true to her/himself, otherwise the work will tend to predictability and mediocrity. The capacity for risk, for contingency, is central to what I do, and as such its outcomes cannot be predicted. My work isn’t about either going with or against the so-called ‘flow’, as it’s not even in the same river to begin with! My work proceeds along a journey of previously unknown events (actions), which in turn create new events (reactions), which trigger more events: the work develops accretively. None of these events or the final outcomes can be imagined by me or anyone else, nor can they be conveyed, even speculatively, to a third party, so the prospect of my being able to fulfil any commercial expectations is irrelevant. The nature of my work resists any easy acceptance by ‘the market’, nullifies any “wishes of the clients” and , thankfully, as I have no idea of any perceived “audience’s expectations”, I’m not obliged to consider it. I guess I’ve been very fortunate in that those who commission me and those who collect my work, approach me principally because they like what I do, and because they like my way of thinking. Gratifyingly, they trust me and very few attempt to impose ideas on me or overtly direct me. That’s not to say I’m not open to engaging in creative conversations with them that might produce different approaches to the work.

?: How are innovation and improvement possible if you’ve established a distinctive style? Is it good to be ahead of your time, even if you hazard not being understood?

One must always embrace and indulge in risk in order to keep one’s work fresh, vital and hopefully relevant. Without the capacity to risk, the will to surrender to it, there is no chance of change. I’m not concerned with any notions of “being ahead of [my] time” and think it’s an impossible and dangerous ambition to have in the first place. Consciously striving to be avant-garde generally just produces self-aggrandising novelty.

Innovation, in any area of life, usually comes about through an individual’s belief in an idea and her/her strength to trust her/his instincts. Breakthrough’s rarely come out of communal ‘group-think’ or from committees. Sir Alec Issigonis who designed the classic Mini car, one of the most successful cars of recent decades, said, “A camel is a horse designed by committee.” He had a clear and uncompromised vision and was committed to driving through his ideas in order to create something new, something special. Crucially, he had the courage to resist pressures to compromise. Had he succumbed to “design by committee” he might have ended up with a camel – or its modern day equivalent, a Reliant Robin.

?: When does the time come to end the creative process, to be content and set the final result free? Or is it always a work-in-progress, with an endless possibility of improvement?

The perennial question: how does an artist know when a piece of work is finished? Intuition kicks in, a kind of sixth sense tells me that a work is finished, but it’s accompanied with the caveat that as a work-in-process, always making itself, always changing by minute degrees, it is therefore always unfinished, just as we are unfinished. Accepting that the works and the processes used in their making are experimental and ever-shifting, being necessarily adaptive, I can go back to it to re-examine and re-work it if I so choose.

?: In case of failure or, worse, a creativity crisis how do you get out of such a hole?

With great difficulty. The creative block is another perennial problem and it’s one I experience a great deal. I usually find that, initially, I have a fairly vague idea as to what a piece of work is about and what I’m hoping to convey with it, and it evolves to a certain point, which I’m usually happy with. However, there are occasions when a process I’ve employed in/on the work creates something genuinely surprising, which may be so disturbing (not necessarily in an adverse way) that it pulls me up, like a horse rearing at a loud noise. Stopped in my tracks by the possible implications of this new happening, I’m obliged to further scrutinise and reconsider my original ideas and intentions. This period of re-examination can be long and frustrating, but it can also be rewarding. Being naturally optimistic, I tend to look for the silver linings in any apparent error or failure. By degrees the ideas

SUCCESS

?: “Success is the ability to go from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm.“ Do you agree with Winston Churchill’s quote?

Absolutely, although I prefer to follow the advice given by one of my favourite writers, Samuel Beckett from his 1983 novella, Worstward Ho, in which he writes, "Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.“

?: Should or can you resist the temptation to recycle a ‘formula’ you're successful with?

Not necessarily. I do occasionally go back to processes and ways of working I’ve used in the past, but only when I consider them to be potentially contextually appropriate, or when I think they might be interesting when used with a completely different approach.

?: Is it desirable to create an ultimate or timeless work? Doesn’t “top of the ladder” bring up the question, “What’s next?” — that is, isn’t such a personal peak “the end”?

I doubt that any artist (or musician, film maker, writer, etc.) consciously aims to produce an “ultimate/timeless work”. Such an aspiration is doomed to fail. I suspect that any artist who decidedly aims to create such a work is either simply naïve or an out and out charlatan. Such a work may well appear, maybe fortuitously, or simply out of hard graft, but it’s very unlikely to be considered as such until well after its creation. Most works of art that we now consider to be masterpieces were not considered as such when they were made. Works by the likes of Vermeer, Rembrandt and Van Gogh, for instance, were generally ignored and sometimes ridiculed in their lifetimes, and all have persistently gone in and out of favour over the centuries.

MY FAVORITE WORK:

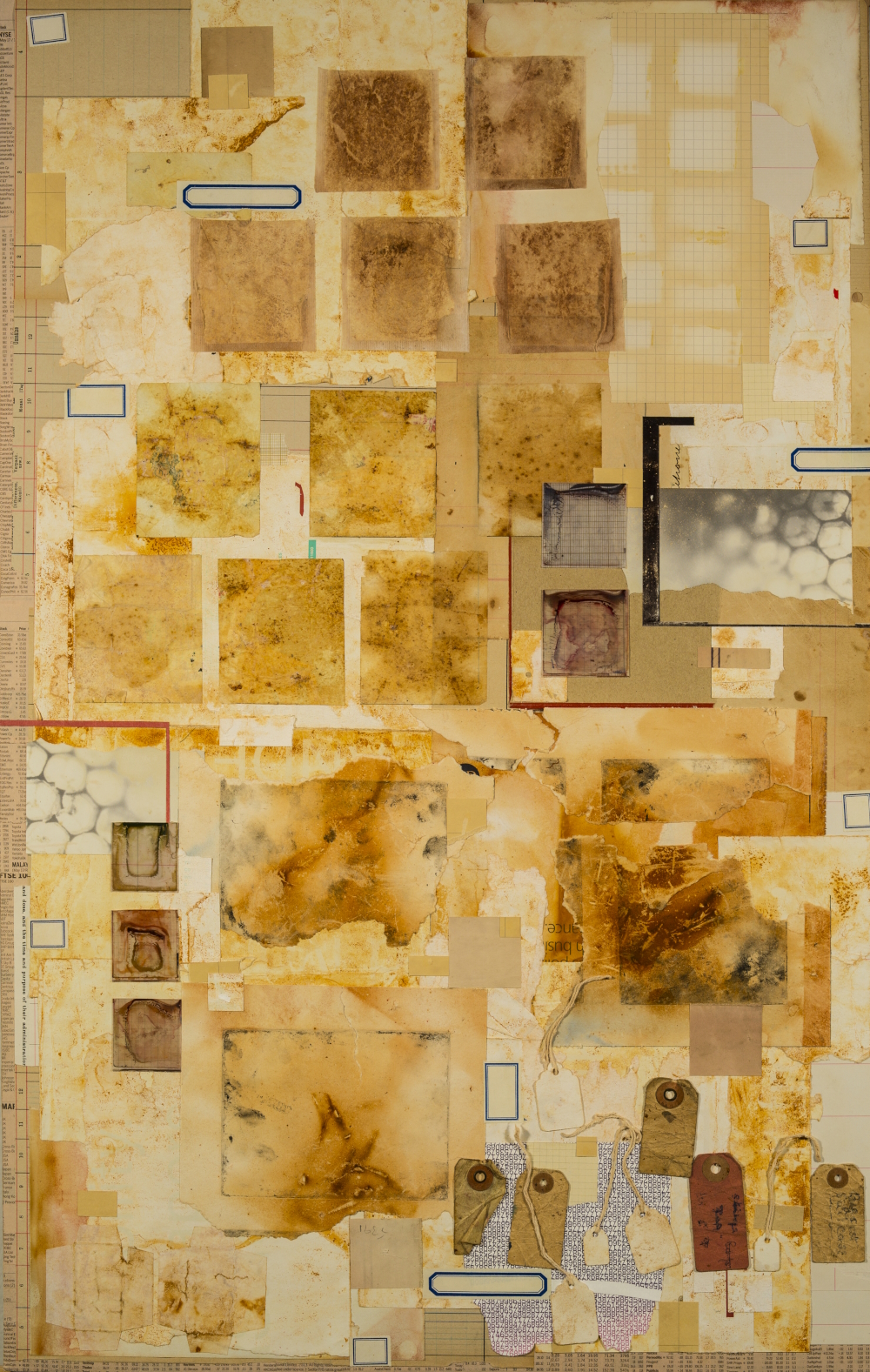

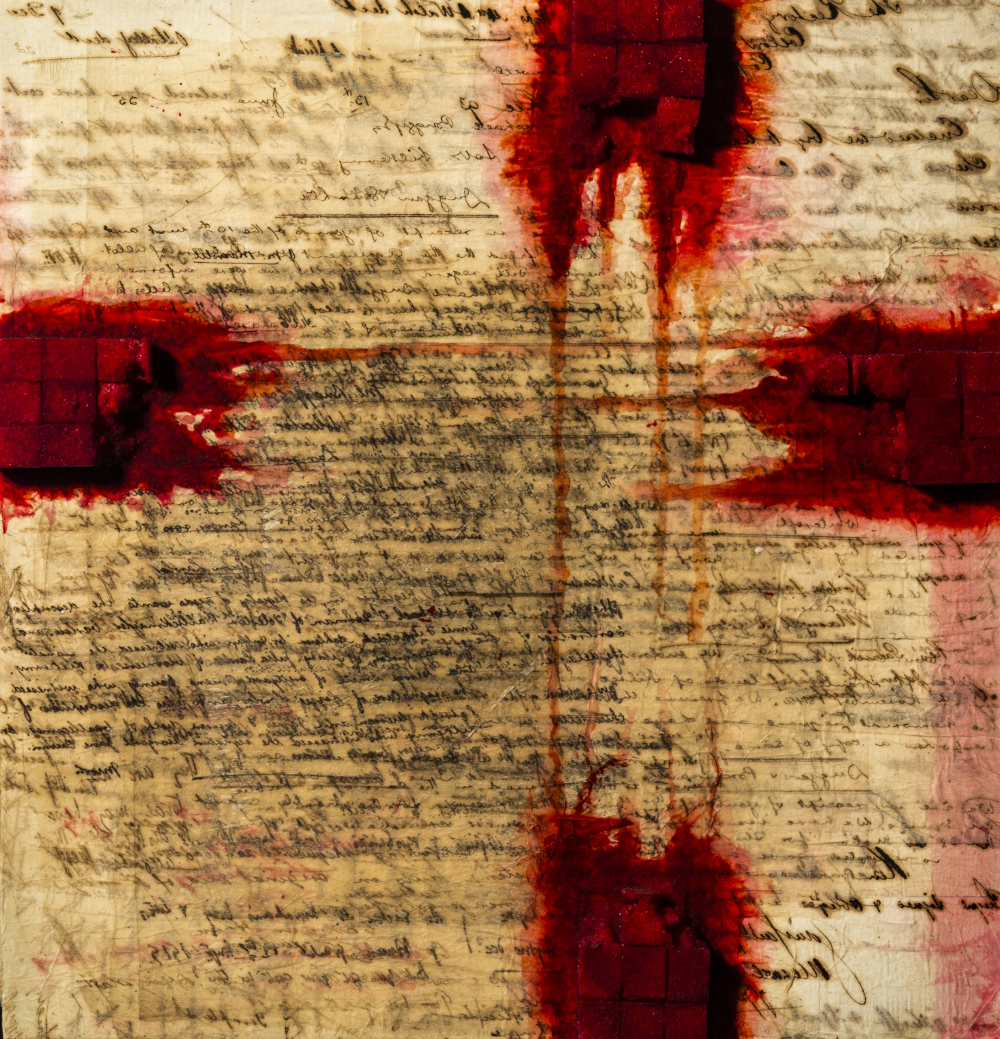

The work, or more precisely the works, that I believe best represents my approaches to making art, and which I am most proud of, is the collection of 30 mixed media pieces I made in 2012 towards possible uses for the Nine Inch Nails album Hesitation Marks. These works subsequently became the focus of the limited edition multiple titled Cargo In The Blood: The Reverse Is Also True, which was published in 2013. I think that the foreword I wrote for Cargo In The Blood provides a good example of my endless curiosity and associative thinking.

Early in the process, an idea of the ‘Black Box’ and the wreckage emerged as a possible, potent analogy for much of the work. Colloquially known as a ‘Black Box’, a Flight Data Recorder is a device used for sensing and recording specific aircraft performance parameters and data points. In the event of a crash, accident investigators extract the information stored within the ‘Black Box’ from which they can extrapolate and interpret retrieved data, which can provide clues as to the probable cause of the crash. By the time the data is extracted it is too late: the catastrophe has already occurred; the chaos of the crash and the wreckage – human and otherwise - that lies grotesquely mangled and spread over acres, silencing reason. The experiences of all those in the crash, and all those impacted by it - the dead, survivors (if any) and their relatives - cannot be gauged.

These ideas led to a shifting area of inquiry hovering between anthropology and forensics, in which trace evidence, discovered, extracted, investigated and deciphered, might suggest other or larger truths. Indexical and metonymic, the forensic trace, a fragment of something unknown, a minute clue, a tell-tale sign, is a contiguous part standing for an absent whole; like a tiny find from an archaeological dig, it carries a larger history.”

The discovery of something unknown can be unsettling or revelatory, provoking consternation or amazement. When confronted by something that is beyond our reach, we can become unhinged or we are awestruck. Our reasoning mind, confounded or fascinated by the unfamiliar, either retreats in confusion or opens wide to the possible. Marvelling at the incomprehensible, at what eludes us, is what feeds our curiosity and prompts questioning. Throughout his life Nobel Laureate physicist Richard Feynham continually demonstrated the primacy of this state of not knowing, of wonder, as the very essence of our quest for understanding.

I’m extremely proud of the resulting works. Made in an intense period of total immersion, which followed almost a year of near complete inertia, in which I felt I’d come to a very serious creative impasse, they re-ignited my capacity to risk, to surrender to the processes at work, and to marry the intellectual with the intuitive and create what I think are some works of both power and beauty.

Another project which I’m very proud of was a multi-media, site specific installation titled Now Then, which was created for the ArtWorks space in Shaw Lodge Mills, a former textile factory in Halifax, Yorkshire in 2015. As with all of the multimedia installations I’ve produced since the 1990s, a new multi-channel, generative sound work was made by myself and my collaborator, multi-instrumentalist and sound engineer, Mike Fearon.

Now Then was a complex work inspired and informed by multiple and very different ideas that I was preoccupied with at the time, including veiled references to my father, who had survived World War Two as a rear gunner in Lancaster bombers, to the ideas of the 14th century ‘hedge priest’ John Ball and of the political activist Thomas Paine, to texts by the writers Virginia Woolf and Samuel Beckett , and the poems of Seamus Heaney.

For Now Then I decided to allow the notion of consciousness as collage to dictate the content and direction of the work in a far less discriminatory and far more porous way. Abandoning any attempts to corral ideas into a coherent whole, acting merely as a receiver, I attempted to surrender to the dynamics of their flow. Avoiding the constraints of analysis and interpretation, I juxtaposed seemingly unrelated ideas and subjects that had absorbed me over the previous few years, into a new configuration. Despite the complexity of its making and the apparent disparity of its parts, the final installation achieved an emotional charge that resonated with many of those who spent time in and within it.