The Singh Twins

unique past modern painters

GB

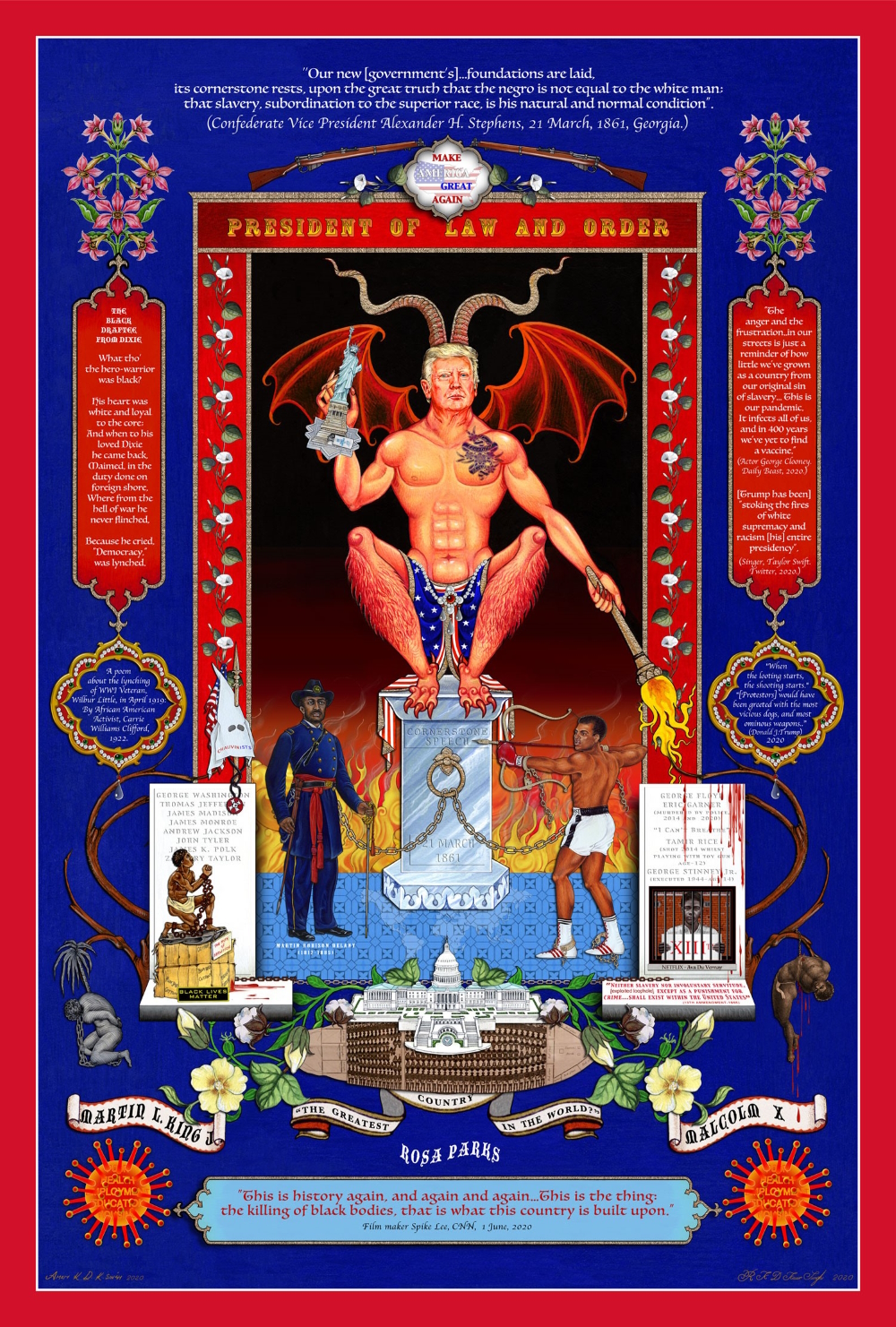

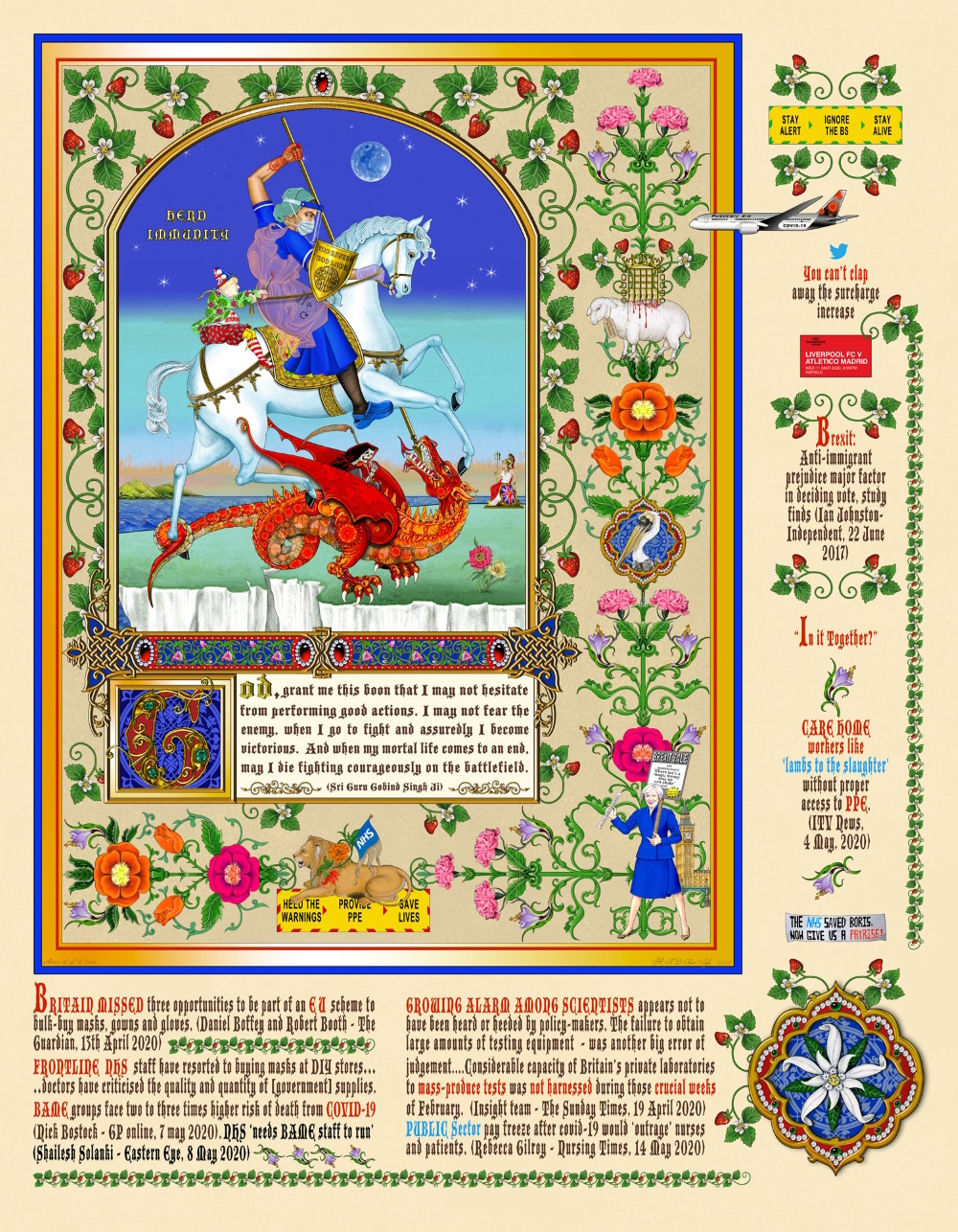

“They are representing the artistic face of modern Britain.“ This quote by famous British historian Sir Simon Michael Schama in his five-part BBC documentary series 'The Face of Britain' (realised in close coop with The National Portrait Gallery, London) underlines the exceptional state of a single-identity artist duo of British-Indian origin. For pioneering a modern revival of Indian miniature painting within their highly decorative, narrative and symbolic contemporary practice the pair received an MBE from Queen Elizabeth II (1926-2022). “Their style is a fusion of Indian tradition and contemporary Western influences“, determines the British online newspaper The Independent. The interchangeable twins label their “provocative and sharply political work“ (English contemporary artist and writer Sir Grayson Perry) “past-modern“ - as apposed to ‘post-modern’. For the recipients of three Honorary Doctorates (Doctor of Fine Arts from the University of Chester; Doctor of Letters from the University of Liverpool and Doctor of Arts from the University of Wolverhampton) who create their artworks together and are mentioned in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History “it is important to challenge established cultural biases!“

The Singh Twins

unique past modern painters

GB

Although since childhood they enjoyed creating art, The Singh Twins always regarded it as a hobby and never intended to become professional artists. They studied the sciences at school, planning to follow in their father’s footsteps and become medical doctors. However, their plans were ruined by the lack of support from their teachers who determined they should be pursuing art instead and believed in the popular cultural stereotype that Asian parents forced their children into careers belonging to the Professions. As a consequence they wrote in the twins’ University applications that they were “only pursuing medicine because of family tradition and parental persuasion“. Unsurprisingly, the native Londoners did not receive offers from any of their chosen Universities to study medicine! The actions of their teachers made the twins even more determined not to take up a degree in art. But fate had other ideas when they enrolled at Chester College (affiliated at that time to the University of Liverpool) to read a BA (Hons) degree in Combined Studies and had no choice but to select a module in 20th Century Art History (alongside their first choices of Comparative Religion and Ecclesiastical History) as the only other subject available within the study timetable! It was the experience they faced within the art department during their time at Chester that was to ‘blame‘ for The Singh Twins’ finally becoming full-time artists. Their wish to express aspects of their non-European traditional, but Asian-rooted, art was degraded and suppressed by the prejudiced art tutors who told them it was “backward and outdated” and had “no place within contemporary art”. The twins disagreed and stuck to their art style as a means to challenge the narrow Eurocentric outlook of the Art Establishment which they saw as a reflection of the wider ‘west is best’ cultural prejudice and negative stereotyping they had grown up with in the UK as British Asians.

If one thinks about these sisters’ early artistic background their career was a logical step for them. The ‘twindividuals‘, as The Singh Twins call themselves in order to challenge the notion of ‘individuality’ which is so important in western society and especially (as was drummed into them by art tutors at College) the contemporary art world, had already shown a real aptitude for drawing together from a very young age. Later, as pupils at Holt Hill Roman Catholic Convent, the stained glass windows and statues in the school chapel nurtured their inspiration and love for colourful, decorative, and symbolic art including Renassiance Art, Art Nouveau and the Pre-Raphaelites - all of which continues to influence their work today.

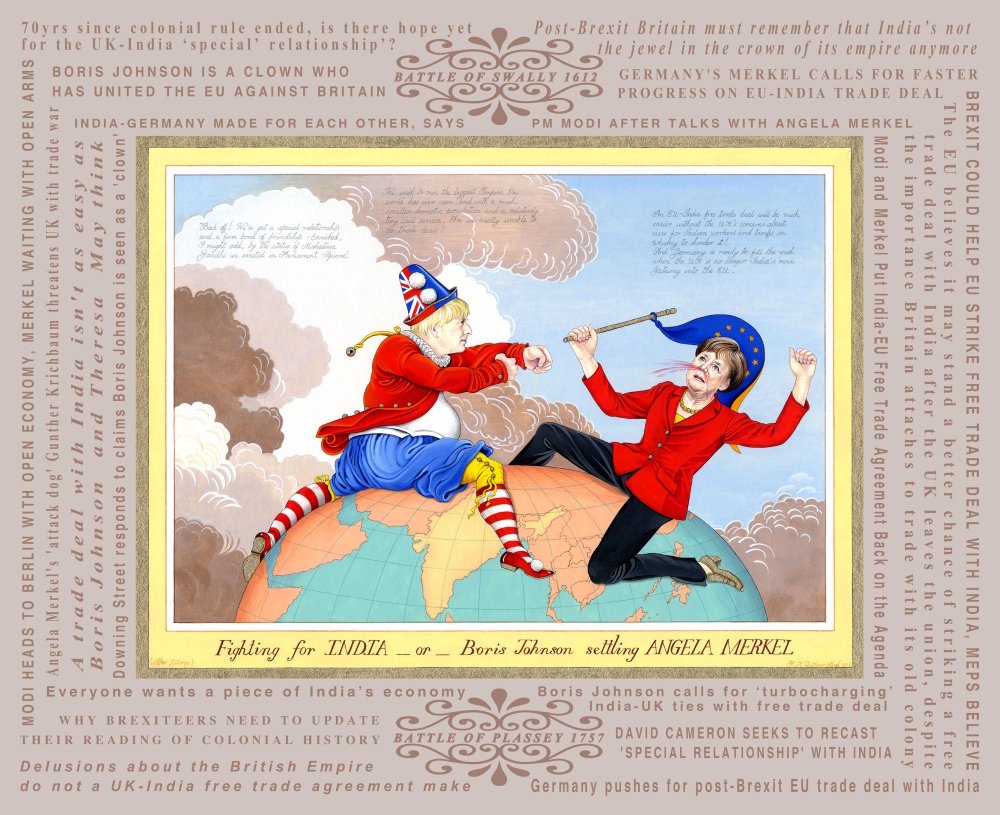

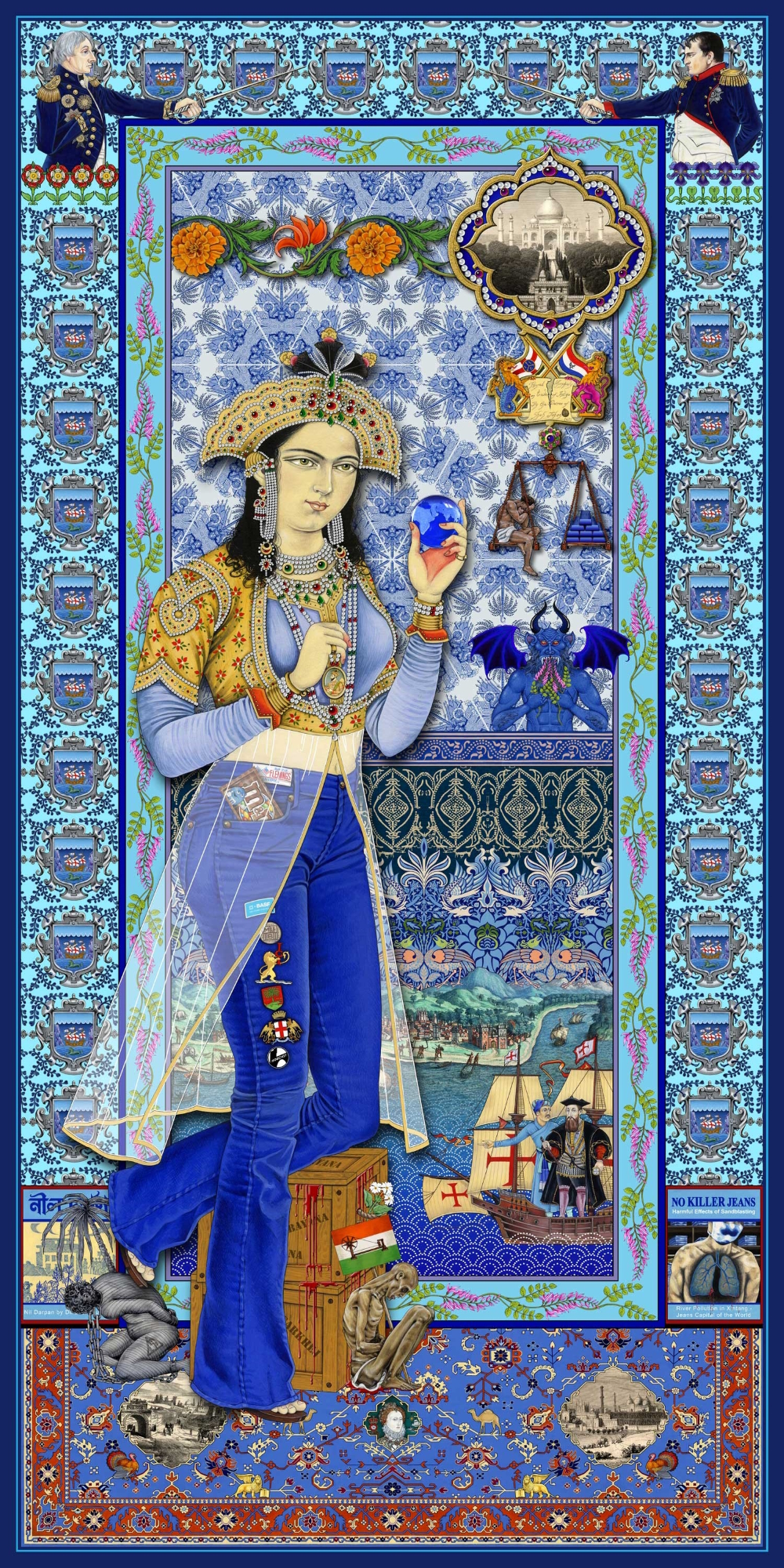

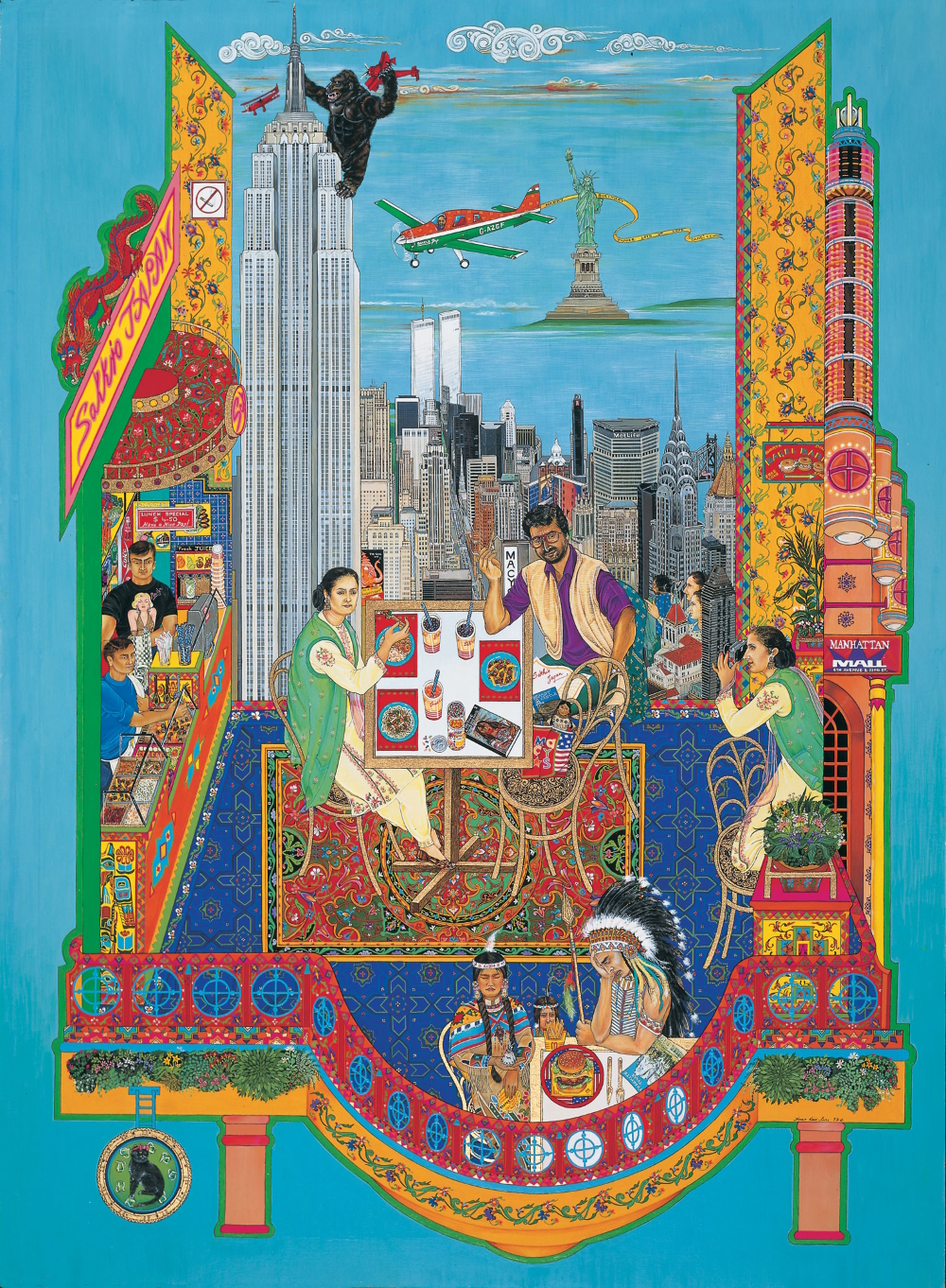

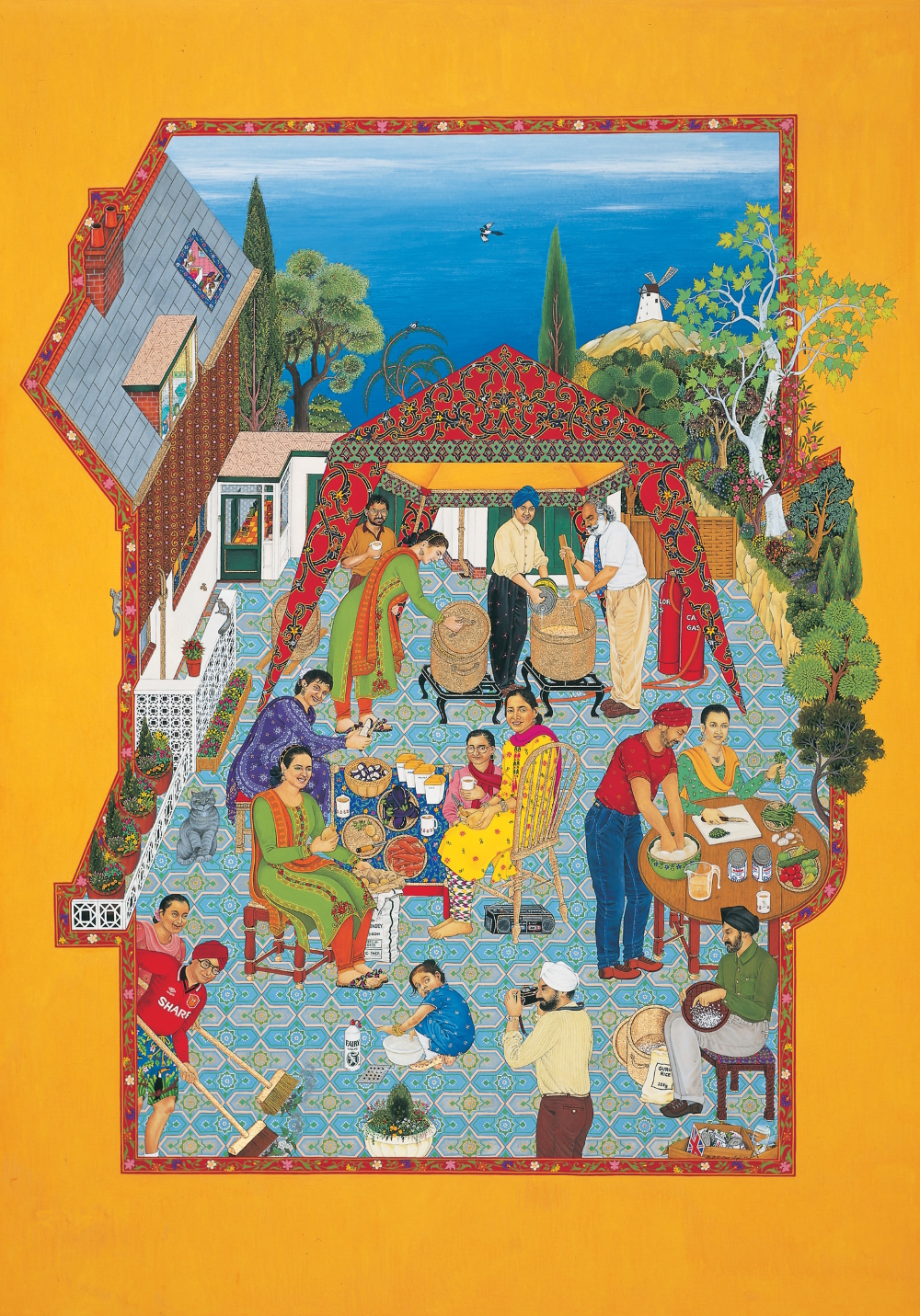

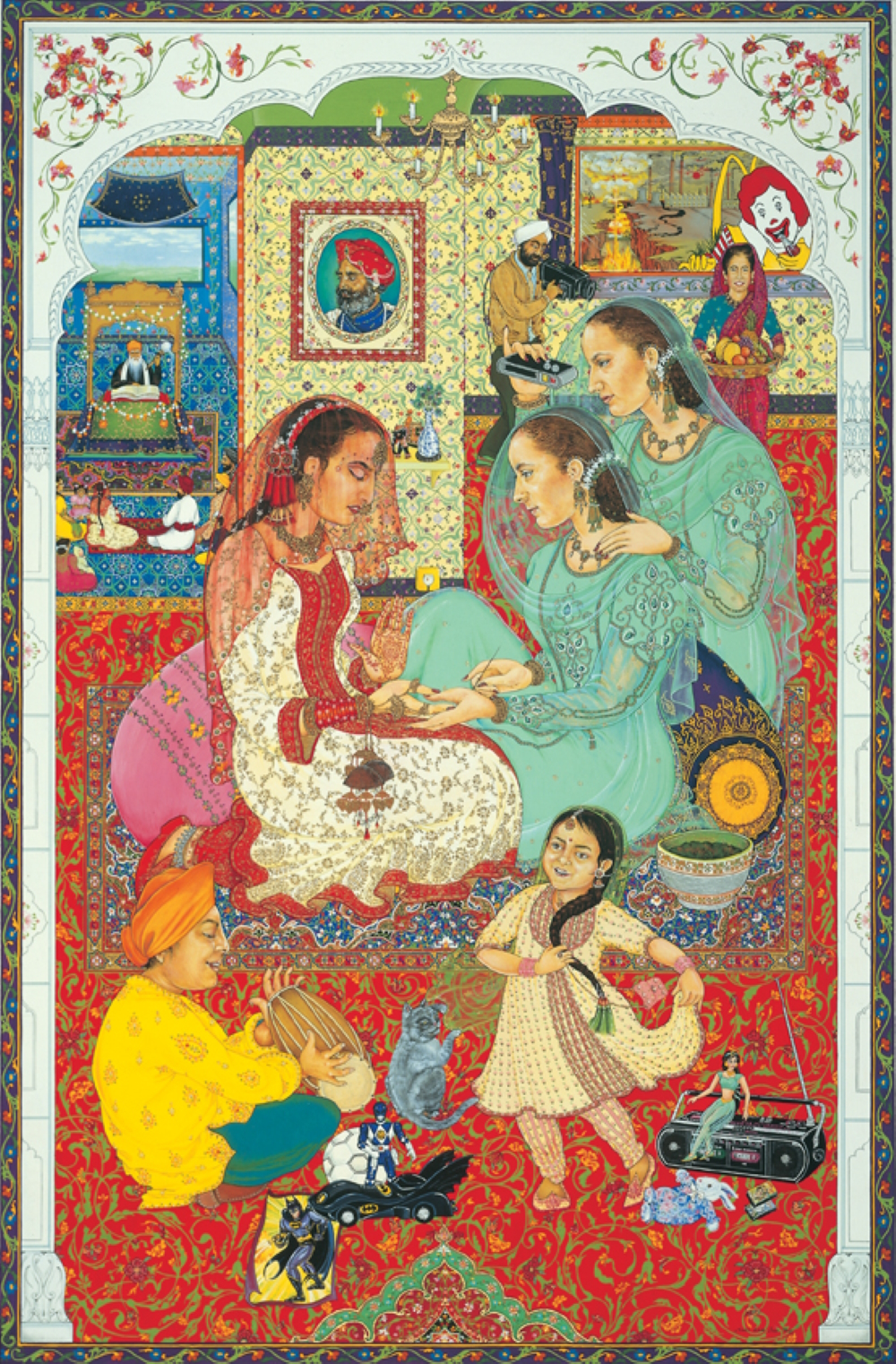

The singular pair’s key experience happened in 1980 when they took an extensive road trip to India with their family where they spent one year travelling around the length and breadth of the country. At the National Museum, Delhi, the twins encountered the tradition of Indian Miniature Painting and were awe inspired by their beautiful jewel-like quality, breathtaking technical skill, minute detail, symbolism, narrative and satire. Disappointed to see the general lack of respect for this tradition within the Indian Contemporary art scene which “was busy aping Western Art styles”, the 13 year old twins decided they wanted to revive the Indian miniature style and bring it to a contemporary audience. On their return to the UK they started in between their school studies to teach themselves the miniature style techniques by copying examples from a book (Imperial Mughal Miniatures by Stuart Cary Welsh) which they had purchased in Delhi. To further their self-education, they later visited the Victoria and Albert Museum where they took close up photos of details from the museum’s rich collection of Indian miniature paintings and enlarged them so that they could see how every brush stroke was made. Their first works executed in the Indian miniature style copied traditional, conventional themes (e.g. portrait of a Maharaja standing on balcony). But it wasn't long before they adapted the style and turned their attention to the modern world starting with depictions of their own family life, celebrating pride in their traditional Indian culture but also their dual Anglo-Indian heritage as a way of challenging the pressures they felt as young British Asians to choose between the two aspects of their identity and conform instead to western values and lifestyles in order to ‘fit in’ to a predominantly white British society where traditional Indian values were, in their personal experience, generally devalued and derided - particularly by the media. As their experiences and interests broadened, they then began to explore social and political issues relating the wider world around them with a particular interest in colonial histories and their legacies: very much seeing themselves as social and political commentators and documenters.

The sisters create their artwork side by side and present themselves as one artist, always exhibiting together and attributing all the works on display jointly as ‘The Singh Twins‘ – regardless of having been made in close collaboration, or by one of them. “Even when we are painting our own separate pieces within a series of works“, they are quoted on ymliverpool.com, “we are side by side, keeping an eye on each other. If one of us gets stuck for an idea or wonders ‘what colour should I use?’ the other one is always there to chip in with advice.“

The Singh Twins‘ métier is thematically broad, as stated by The Guardian: “Ranging from the intensely personal to the deeply political, they draw on the tradition of Indian miniature art, every available inch of their work crammed with patterns, colours and references. At the same time, their paintings address familiar, universal subjects such as globalisation, migration and celebrity culture.“ First of all the inseparable pair has to decide upon a topic to cover artistically (“Our work has always been about looking at the past and making it relevant today. History is the starting point“ – YM Liverpool). Then complex research follows. According to theartssociety.org, “once [this] is complete, they discuss the themes and stories they want to explore. They then, with a focus that is identical, become two artists working as one. ‘We divide the work between us,’ they explain... Working together so closely, they say they are ‘always conscious of what the other is doing’... Due to the level of detail, each artwork can take anything between 50 and 1,000 hours to execute.“ For the two academic artists, drawing upon the language and conventions of traditional styles of art from ancient times is their first love. But they also go with the times and embrace modern multimedia, combining digital created imaginary with classic hand-painted details. In addition the pair have diversified into both poetry and filmmaking.

Their award-winning output sits in public as well as private collections across the world and is on display in museums and galleries of course. “In 2002, their oeuvre was the subject of an exhibition at the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi, making them only the second British-born artists, after Henry Moore, to be accorded such an honour“ (Wikipedia).

The success and recognition that the multi-awarded Honorary Scousers of Liverpool get, is the reward of refusing to bend to the dictates of the Art Establishment in order to be accepted. On their website The Singh Twins inform that their “adherence to the miniature style became a political statement: A way of asserting the right to choose a visual language which was true to our own interests in art and the natural affiliation and pride we felt for our Asian heritage, and challenging the hypocrisy of an Establishment which advocated the western values of ‘self expression’ and ‘individuality’ as the ‘be all and end all’ of Modern Art, yet denied the validity of anything which did not comply with the expectations dictated by its selective, Eurocentric perspective. It was against this background that our practice of working and exhibiting together (as well as dressing identically) was also formed as a rebellion against a system that judged art according to western values and definitions.“

The Singh Twins work in their studio that‘s close to the extended family home where they live with their father, uncles and cousins in Liverpool (UK).

Interview May 2023

Twindividuals Collaborations: the Fusion of Western Contemporary and Asian Traditional Artworld

INTUITION/IMAGINATION

?: How does intuition present itself to you – in form of a suspicious impression, a spontaneous visualisation or whatever - maybe in dreams?

We visualise in our minds' eye.

?: Will any ideas be written down immediately and archived?

Yes, very often we write ideas down as they come to us - even if that happens to be in the middle of the night! We always keep notes, based on the research we carry out for each artwork. Sometimes those ideas don’t come to fruition (in terms of creating artwork from them) until several years later.

?: How do you come up with good or extraordinary ideas?

These usually stem from a life experience and personal interests - for example, a book we might have read; a documentary or news story we might have watched; places we’ve have visited; the racial prejudice we’ve experienced growing up in England as British Asians and as British artists inspired by a traditional Indian art form. But many of our best ideas have also been informed by a client’s brief such as our latest commission for Manchester Museum: a 17 meter long mural exploring the colonial ‘riches to rags, rags to riches’ relationship between India and Britain. In both cases we build on our initial ideas through meticulous research which leads to further, often unexpected avenues of exploration that impact the direction which the final artwork takes.

?: Do you feel that new creative ideas come as a whole or do you get like a little seed of inspiration that evolves into something else and has to be realized by endless trials and errors in form of constant developments until the final result?

Definitely more the latter case - to the extend that the final composition can end up being quite different to what we first had in our mind!

?: What if there is a deadline, but no intuition? Does the first fuel the latter maybe?

We’ve never faced that situation because before we agree to take on any commission, we first make sure that we are interested in the subject and think about how we might approach it. If no creative ideas come to us, at that stage then we wouldn't do it - so the deadline doesn’t come into it. And, if we are interested in the commission subject, then we always consider whether or not it is possible to deliver in time for the deadline. If there is any doubt about meeting the deadline, then we don’t take on the work.

INSPIRATION

?: What inspires you and how do you stimulate this special form of imaginativeness?

In terms of our asthetic style we are inspired by the beautiful, decorative, symbolic, narrative art of the Renaissance, Indian miniatures, Art Nouveau, PrepRaphaelites as well as 18th Century British political satire (especially British caricaturist James Gillray). In terms of our themes, we draw inspiration from multiple sources - from history (especially the age of Empire and Colonialism) and its modern day legacies; religious art; political issues and current debates around environmentalism and ethical consumerism for example. We very much see ourselves a social and political commentators.

?: How do you filter between ideas that are worthwhile pursuing and bad ones that you just let go of?

We actually can’t recall having had any bad ideas. But we have had to let go of many ideas that we have simply not had the time to pursue. And they are usually the ones we are interested in pursuing for ourselves as apposed to those relating to paid work which inevitably have to take priority.

?: Does an idea need to appeal to you primarily or is its commercial potential an essential factor?

Definitely the former. We never take on work that doesn't appeal to us because we have to enjoy what we are doing and feel its important to have a purpose and meaning in what we create - otherwise the art will suffer. If your heart isn't in something, you can’t do justice to it. And we owe to our audiences and to our clients to create the best work we can.

?: Do you revisit old ideas or check what colleagues or competitors are up to at times?

Yes, there have been a few occasions where we’ve revisited an old idea that perhaps was put on the back boiler because we had to turn our attention to something more pressing. Or else, because we felt it would benefit from further reflection and research over a longer period of time. This happened for example with our artwork ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’ which depicts the Indian Government’s military attack on the Sikh ‘Golden Temple’ of Amritsar in 1984. Almost immediately after the event we created a small work focusing on the loss of innocent life: an expression of our personal anger and frustration about what had happened and the lack of fair media coverage due to Indian government censorship at that time. But many years later we went on to develop the theme in a much larger work reflecting ongoing debates about 84 and its aftermath, as well as new information bought to light by organisations such as Amnesty that exposed the extent of atrocities committed against the Sikhs. This later work also placed the attack within the universal context of innocent suffering at the hands of political greed and ambition globally.

To be honest, we’re usually so busy concentrating on our own work, we don’t really have time to keep a constant eye on what other artists in general are up to. Our artwork is very unique, so we don't feel we have any competitors to worry about and just concentrate on making our own waves in the art world on our own terms! On the other hand, we do enjoy from time to time checking on what our personal artist friends are up to by following them on Instagram, etc. - but that’s more to show our support for their work.

CREATIVITY

?: What time or environment best suits your creative work process — for example, a time and place of tranquility or of pressure? Which path do you take from theory or idea to creation?

We have always worked from home, which suits us as it’s a comfy environment and enables us to juggle work with home life. Its also a more practical option to having a studio outside as, more often than not, we find that we are creating work well into the early hours of the morning. We love to play music whilst we work which creates a relaxing environment - even though some of music we choose might not necessary be classed as soft and tranquil! We hate working under pressure but are sometimes forced to do it when juggling several projects at one time.

Initial concepts are always followed by a period of research which can takes days to months depending on the subject and the number of works we are creating for a particular project. We carry out initial general research together and then, having identified general themes to explore further, divide these between us to carry on with more detailed research.

?: What’s better in the realization process — for example, speed and forcing creativity by grasping the magic of the moment or a slow, ripening process for implementation and elaboration?

The complex nature of the work we do (both in terms of planning and practical execution) means that our creative process can never be rushed - even though we sometimes wish it could be! We have found that you can’t force creativity. It always results in a blank page, or mind, and is counterproductive as you usually have to start all over again to get things right.

?: Do you have any specific strategies you use when you're feeling stuck creatively?

Turn to each other for suggestions and to brain storm ideas. Failing that, we take a break and sleep on it.

?: How important are self-doubt and criticism by others during such a process?

It’s always best to be both self critical and also open to accepting constructive criticism from others. Only then can you be sure to push your own boundaries and develop the very best work you can. We’ve always worked as a team - not only being inspired by and bouncing ideas off each other but remaining a united front in carving out our own niche within a contemporary art world that has proved to be unaccepting of expressions of art such as ours - i.e. which refuse to comply with its narrow Eurocentric definition and evaluations of art.

?: Should a creative person always stay true to him- or herself, including taking risks and going against the flow, or must the person, for reasons of commercial survival, make concessions to the demands of the market, the wishes of clients and the audience’s expectations?

We guess it’s a personal choice. But it’s always been important for us to stay true to ourselves and insist, even at the expense of risking loosing an opportunity (which we have done in the past), that our art be accepted on its terms rather than cow towing to the dictates of the Art Establishment or art market. This conviction stems back to the prejudice we faced from art tutors at University who dismissed our work as “backward”, “outdated” and “having no place in contemporary art”. Within that context, staying true to ourselves and our style is a political statement in itself - one that challenges narrow-minded attitudes and cultural assumptions. At the same time, we also recognise that creatives need to make a living and sometimes that might involve compromise or bending your style according to the client’s needs. And in those circumstances we feel it’s entirely legitimate to do that.

?: How are innovation and improvement possible if you’ve established a distinctive style? Is it good to be ahead of your time, even if you hazard not being understood?

Firstly, we would argue that there is no such thing as true innovation when it comes to creativity in the sense that art cannot be produced from a vacuum because it will always be inspired by something that came before it - consciously or unconsciously. We also don't subscribe to the idea that art must be innovative in order to be valued (which is often an underlying presumption regarding the question of innovation). Nor do we believe that artists should feel pressured to change their style just to be seen to be innovative. Having said that, we also believe that it is still possible for artists associated with a distinctive style to continue to innovate as a natural process their ongoing exposure to changing influences (artistic or otherwise) and experimentation with different mediums. Many artists such as Picasso for example are known for innovating a number of different styles throughout their career. Traits of our own earlier style in painting (which is known for it’s modern development of the Indian miniature) continue to follow through in our later work which also reflects other global traditions and adopts modern digital technologies - But the styles are all still recognisably ‘The Singh Twins’.

We would much rather be ahead of our time - even if that means not being understood at the time - because it sets you apart from everyone else and you are, therefore, more likely to be remembered and your work have a lasting impact. Most of the greatest names in art history (E.g. Leonardo Da Vinci) were ahead of their time so its a good club to belong to! Plus, isn’t it generally better to be the one who leads rather than the one who follows?

?: When does the time come to end the creative process, to be content and set the final result free? Or is it always a work-in-progress, with an endless possibility of improvement?

It’s a continual work in process with details added and reworked and with narratives changing all the time. So creativity for us usually stops when we’ve run out of composition space!

?: In case of failure or, worse, a creativity crisis how do you get out of such a hole?

Thankfully, we can’t really think of any real crisis like that, which we’ve had to deal with.

SUCCESS

?: Should or can you resist the temptation to recycle a ‘formula’ you're successful with?

Not necessarily. As the saying goes, “if it’s not broken, don't try to fix it”. We don’t believe in change for the sake of change, or innovation for the sake of innovation. So, if what you create is successful and you love doing it, and still feel it has value and meaning - then carry on!

?: Is it desirable to create an ultimate or timeless work? Doesn’t “top of the ladder” bring up the question, “What’s next?” — that is, isn’t such a personal peak “the end”?

With creativity, we don't think there is ever “the end”. Sometimes you may feel that you’ve reached a personal peak with a particular body of work (as we did, in fact, with our ‘Slaves of Fashion’ series when it launched at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, in 2018) and think ‘what’s next?’. But then you find that there’s always another challenge waiting round the corner to push you that little bit further and others avenues of interest, or change in creative technologies to spark your imagination and enable you to create and present your art in new and even better ways.

OUR FAVORITE WORK:

It has to be our latest work ‘Riches to Rags, Rags to Riches’. This is a 17 meter long mural artwork commissioned by Manchester Museum for its new South Asia Gallery which opened in February 2023. It was a massive challenge to create such a large scale work in a very tight deadline and we are really proud of the end result which truly represents our work, both in terms of the kinds of themes we love to explore and its asthetics - presenting complex narratives around Imperialism, colonialism and their modern day legacies through a highly decorative style rich in symbolism and political satire designed to challenge opinions and provoke debate.